A light footprint won’t work in Afghanistan. Just look at the Horn of Africa for all the reasons why not.

A light footprint won’t work in Afghanistan. Just look at the Horn of Africa for all the reasons why not.

As the Afghanistan strategy review dominates conversations in Washington, President Barack Obama’s advisors appear split over whether to fully resource a counterinsurgency or scale back the effort to a more limited, counterterrorism approach. Vice President Joe Biden and others, fearing an open-ended engagement, have argued that a light footprint that features Predator drones and special operations forces would be the best way to counter al Qaeda and other Islamist groups. The reported strategy would take boots off the ground, lessening U.S. casualties even as airstrikes continue to target high-value targets, such as those responsible for the September 11 attacks. To some it may sound like the perfect casualty- and commitment-free plan.

Unfortunately, we have seen such an approach before. Over the last 18 years, Somalia has become the poster child for the shortcomings of light engagement peppered with misguided attempts at counterterrorism intervention. If the United States pursues a similar strategy in Afghanistan, the result will be equally catastrophic. And this time, the new Somalia will be right in the heart of the world’s most volatile region.

As in Afghanistan, the United States began its engagement in Somalia two decades ago with the deployment of troops. The Bill Clinton administration pulled out after just 19 months, when casualties mounted and there was no end in sight to the conflict. Today, 15 years of light footprint later, Somalia remains a breeding ground for a host of Islamists groups, many with connections to al Qaeda. The country is technically ruled by a weak Transitional Federal Government — the 14th attempt at establishing authority in almost as many years. But the administration controls but a few neighborhoods of Mogadishu, holding the Islamist groups at bay only with the help of African Union troops who act as de facto bodyguards.

As Islamist insurgents have gained ground, the United States has tried to contain the damage with targeted strikes utilizing special operations forces. In January 2007, for instance, attacks by an AC-130 gunship and attack helicopters killed at least 31 people, many of them suspected Islamist militants. More recently, on Sept. 14, Navy SEALs swooped down in helicopters and shot up a vehicle carrying Saleh Ali Saleh Nabhan, an al Qaeda leader thought to be responsible for the 1998 bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania.

Despite these few successful raids, Islamist groups — and other malign elements such as the pirates who terrorize ships off the Horn of Africa — appear stronger than ever in Somalia. It has proven difficult to decapitate the Islamists with airstrikes alone, thanks to poor intelligence in such a chaotic climate. And far from crippling terrorist groups, U.S. strikes often cause enough collateral damage to drive more aggrieved people into the insurgent camp. These attacks have also had the unintended effect of bringing disparate insurgent elements closer together. The patchwork of Islamist groups have put aside their clan-based divisions and coalesced around a common cause, forming far more monolithic — and more dangerous — groups such as al-Shabab and Hizbul Islam.

Nor has halfhearted financial, military, and diplomatic support for the Somali government, whether it’s from the African Union, Ethiopia, the United States, or the United Nations, done anything to curtail the Islamists. Instead, it has had the opposite effect. International backing has allowed Islamist groups to portray subsequent interim regimes as puppets of the West, further discrediting the weak bodies among the Somali people. A U.S.-backed Ethiopian intervention to install a transitional government in 2007 made matters even worse; Ethiopians were widely resented, giving the Islamist opposition a convenient enemy against which to fight. Ethiopia pulled out its forces in January, leaving Somalia as much of a mess as ever.

No wonder U.S. officials fear that Somalia is becoming a major al Qaeda safe haven — with an ominous connection to the continental United States, home to many Somali refugees. Some of these U.S. citizens have gone back to fight for Islamist groups. And in the future, there is always the danger that other immigrants, radicalized by the U.S. attacks, will wage war directly on their adopted homeland.

Even if the United States and its allies wanted to devote major resources to stabilizing the situation, it would be hard to do so now, after years of chronic neglect. Somalia lacks security forces that could secure neighborhoods and prevent them from becoming havens for terrorists or pirates. More fatally, Somalis have lost whatever faith they might once have had not only in the United States but also in international organizations such as the United Nations, the International Committee of the Red Cross, and the African Union. Years of empty promises and failed programs have sullied the reputations of aid workers and peacekeepers, limiting the prospects for any future engagement.

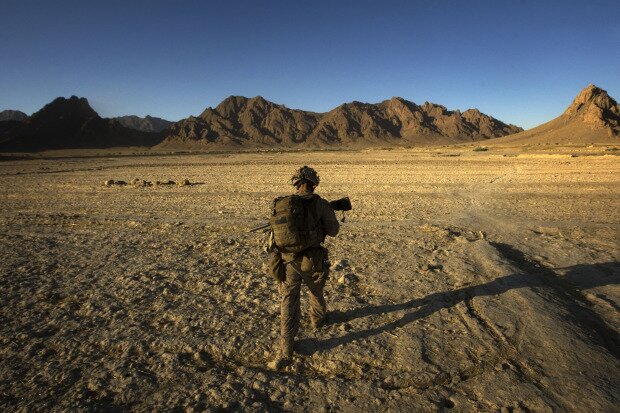

If the United States were to start drawing down forces in Afghanistan — a move that would undoubtedly spark withdrawals by many NATO allies — it is not hard to imagine Afghanistan spiraling downward to become a “Somalia on steroids.” In the 1990s, both were gripped by internecine fighting among brutal warlords. In Afghanistan, the chaos allowed for the emergence of the Taliban, an Islamist group similar to Somalia’s al-Shabab. And as recent civilian casualties have made painfully clear, U.S. counterterrorism strikes there have been no more effective than in Somalia. Drone strikes should certainly play a role in hunting high-value targets, but they are effective only when backed by actionable local intelligence gathered from secure Afghans. Relying solely on air power will only serve to alienate the populace in the long run.

Although the time to win the hearts and minds of the Somalis may have come and gone, it’s still not too late for the Afghan people. One of the bright spots in the war is the Taliban’s abysmal approval rating. An ABC-BBC poll released in February revealed that only 4 percent of Afghans would prefer rule by the Taliban. And though the corruption surrounding the recent presidential election has undermined Hamid Karzai’s government, the damage can still be undone, particularly if the Afghan government works in conjunction with coalition forces to improve the delivery of basic services and security. Such a commitment will require considerably more troops than are currently on the ground. This is the strategy envisioned by the U.S. commanding officer in Kabul, Gen. Stanley McChrystal.

Obama is right to pause and consider all the ramifications of sending more Americans into harm’s way. But if the administration’s ongoing strategy review is honest and rigorous, it should conclude that there is really no alternative — that reverting to a counterterrorism model risks turning Afghanistan into another Somalia. Absent a significant foreign troop presence and an accompanying counterinsurgency approach, the Afghan government would likely fall to warlordism or to the Taliban. The United States and its allies would then have no choice but to intervene selectively. And as in Somalia, a light footprint that targets terrorists without protecting the people would only serve to discredit the international community in the eyes of the Afghans.

Some might be prepared to live with that eventuality, as we currently live with the chaos in Somalia. But though the violence from Somalia certainly has spilled across borders in the form of terrorism and piracy, the danger emanating from a failed Afghanistan would be far greater. The terrorist groups that are based in South Asia — notably al Qaeda — have a more international focus and greater operational capacity than does al-Shabab. And, of course, Afghanistan is located next to another unstable state that has nuclear weapons. Should Pakistan, too, become another Somalia, the world would have a true nightmare scenario on its hands. A drawdown by the West in Afghanistan would only make that bad dream more likely.

_____

BY RICHARD BENNET

Source: Foreign Policy