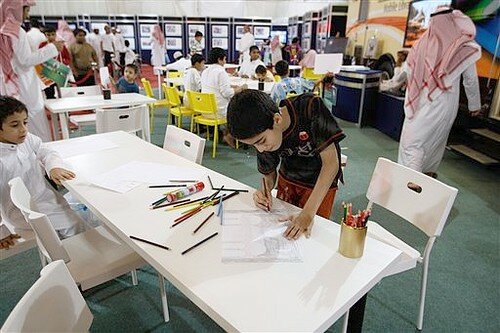

RIYADH, Saudi Arabia (AP) — Young men spray hoses in a car-washing contest and play pool. Children make paper crowns in an art class, while their parents have a picnic. Alongside the fun and games, Muslim clerics answer questions about jihad or give lectures about the proper dress for women.

RIYADH, Saudi Arabia (AP) — Young men spray hoses in a car-washing contest and play pool. Children make paper crowns in an art class, while their parents have a picnic. Alongside the fun and games, Muslim clerics answer questions about jihad or give lectures about the proper dress for women.

This is Islamic summer camp, and it’s part of Saudi Arabia’s campaign to eliminate al-Qaida.

Saudi Arabia says it’s waging a “war of minds” against extremist ideology, alongside the fierce security crackdown that has killed or arrested many al-Qaida leaders over the past six years. To do so, the kingdom plans to expand a broad public campaign aimed at preventing young people from being drawn to radicalism.

“We are working on the men of the future,” Abdulrahman Alhadlaq, general director of the Interior Ministry’s Ideological Security Directorate, told The Associated Press.

Islamic summer camps are a key part of the program, attended by thousands of families who consult with government-backed clerics instilling what Saudi authorities call a moderate message.

The teachings at the camps are still ultraconservative, in line with the kingdom’s strict Wahhabi interpretation of Islam — but the clerics drill the message that youth should turn to approved religious authorities for guidance, not radical preachers. For example, on the issue of jihad, or holy war, they teach that it can only be waged on the orders of the head of state.

“It is … essentially about obedience, loyalty and recognition of authority,” said Christopher Boucek, an associate at Washington’s Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, who has studied the camp programs. “That is what is stressed over and over again in these programs: Loyalty to the state and recognition that there are certain correct and qualified sources to follow.”

Boucek said it will take a long time to evaluate the programs’ effectiveness. “In many ways, these are generational projects,” he said.

The kingdom’s emphasis on ideological campaigns is a stark change from the defensive stance it took immediately after the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks in the United States.

Fifteen of the 19 hijackers were Saudis, prompting a storm of criticism in the U.S. that Saudi Arabia’s Wahhabi thought fueled radicalism. Saudi Arabia staunchly denied the existence of any radical trend on its soil, dismissing warnings of al-Qaida’s influence.

It was not until 2003, when al-Qaida launched a campaign of attacks in Saudi Arabia targeting foreigners and oil infrastructure in a bid to bring down the ruling family, that the kingdom seriously unleashed its security crackdown.

The government followed with a “rehabilitation” program seeking to reform detained militants, in which clerics teach that al-Qaida’s calls for violence are un-Islamic.

Saudi Arabia has come under heavy criticism over its crackdown. Amnesty International condemned the use of torture against suspected militants. In August, New York-based Human Rights Watch said the kingdom is still holding 3,000 suspects without trial and is forcing them to undergo rehabilitation.

Saudi officials say their approach has succeeded in breaking al-Qaida’s leadership and wrecking its ability to reorganize. Al-Qaida has regrouped in neighboring Yemen, but Saudi officials say it is having difficulty gaining new Saudi recruits.

The government is soon expected to endorse a National Strategy to Counter Radicalization, which broadens the ideological campaign to the entire public. Besides the summer camps, which began several years ago, the plan calls for increasing employment and addressing grievances that militants exploit to recruit Saudis.

The government has doubled the number of universities to take in more students and has increased the number of students who study abroad so they get exposed to other cultures. It is also arranging with private companies to provide paid training for Saudis who can’t find jobs.

The summer camps have proved popular. The 3-year-old Rabwat Arriyadh camp in the capital — one of several organized by the Islamic Affairs Ministry around the country — attracts 700,000 visitors annually, with families attending every evening for three weeks.

Part of the curriculum is simply to have fun, not a minor thing in this kingdom where sources of entertainment are sparse. It also counters radicals’ message that religion must eclipse all earthly matters. Girls and boys of all ages separately participate in games and sports, everything from volleyball to car-washing contests. The camp is segregated by sexes as is every aspect of public life in Saudi Arabia.

At the same time, the young people and parents attend lectures by Islamic clerics. They are encouraged to discuss their views on jihad and Osama bin Laden, al-Qaida’s Saudi-born leader, and a cleric then “rectifies any radical misunderstandings,” said ministry official Mohammed Mushawah.

The clerics also advise on religious matters in general — and their answers reflect Saudi society’s deep conservatism. In past lectures, one cleric denounced the “decadent” influence of Western movies and television. Another urged husbands and fathers to ensure women wear the Islamic headscarf.

Evan F. Kohlman, an analyst at the NEFA Foundation in Washington, said the program “couldn’t hurt.”

The message may still be ultraconservative, he said, “but you have to speak to people in language that they’re going to respect and … the only people that hardcore extremists in Saudi Arabia listen to are the clergy.”

Alhadlaq said the strategy is based on extensive studies of why Saudis join al-Qaida. The average Saudi al-Qaida militant is a high-school graduate from a middle-class background, usually from a family larger than the Saudi average of 6.5 members per family, making parental control weak. Almost a third had traveled to hot spots like Afghanistan and Iraq.

Studies found that the main reason for joining militant groups is anger over issues like the wars in Iraq or Afghanistan or the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Alhadlaq said. Next are poverty and unemployment, followed by resentment over government attempts at liberalization.

Preventing the adoption of extremist mindsets is a challenge, said Alhadlaq. “You can’t open up everybody’s mind to determine if he’s OK or not. That’s what makes it hard.”

“Sometimes you sit with a radical guy, and you say, ‘He’s a good guy,’” he said. “But inside his mind, he’s got a different story. Change needs time.”

Source: Associated Press

By DONNA ABU-NASR Associated Press Writer

Photo: Hassan Ammar, AP