DADAAB, KENYA – The U.S.-backed government of Somalia and its Kenyan allies have recruited hundreds of Somali refugees, including children, to fight in a war against al-Shabab, an Islamist militia linked to al-Qaeda, according to former recruits, their relatives and community leaders.

DADAAB, KENYA – The U.S.-backed government of Somalia and its Kenyan allies have recruited hundreds of Somali refugees, including children, to fight in a war against al-Shabab, an Islamist militia linked to al-Qaeda, according to former recruits, their relatives and community leaders.

Many of the recruits were taken from the sprawling Dadaab refugee camps in northeastern Kenya, which borders Somalia. Somali government recruiters and Kenyan soldiers came to the camps late last year, promising refugees as much as $600 a month to join a force advertised as supported by the United Nations or the United States, the former recruits and their families said.

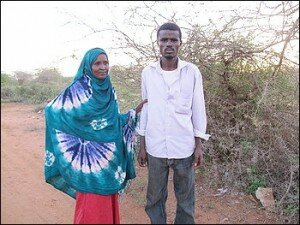

“They have stolen my son from me,” said Noor Muhamed, 70, a paraplegic refugee whose son Abdi was recruited.

Across this region, children and young men are vanishing. All sides in Somalia’s conflict are recruiting refugees to fight in a remote battleground in the global war on terrorism from which they fled, community leaders say.

It is unclear whether recruiting by the governments of Kenya and Somalia is ongoing. But their military officers continue to train refugees at a heavily guarded base near the northern Kenyan town of Isiolo as the Somali government prepares for a long-planned offensive against the Shabab.

A second camp is in Manyani, a training station for the Kenya Wildlife Service in southern Kenya, according to former recruits, relatives, community leaders and U.N. investigators.

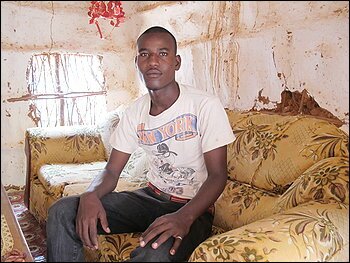

“They told us we were going to Somalia soon,” said Hassan Farah, 23, who escaped from the Isiolo camp last month.

Farah, who was injured in a 2008 bombing in the Somali capital of Mogadishu, first spent more than two months at Manyani. “I saw 12-year-old children at the camp,” said Farah, who has a jagged scar on his left arm. He escaped by bribing a water truck driver to sneak him out.

The Kenyan government has acknowledged that it is helping train police officers for Somalia’s weak interim government but said that the recruits were flown in from Mogadishu. “No one is recruited from the refugee camps,” said Alfred Mutua, a Kenyan government spokesman.

The Kenyan government has acknowledged that it is helping train police officers for Somalia’s weak interim government but said that the recruits were flown in from Mogadishu. “No one is recruited from the refugee camps,” said Alfred Mutua, a Kenyan government spokesman.

But a recent U.N. report on Somalia confirmed the recruitment of refugees, including underage youths, for military training. Kenya’s training program, the report said, is a violation of a U.N. arms embargo, which requires nations to get permission from the U.N. Security Council before assisting Somalia’s security efforts.

Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah, the U.N. special representative to Somalia, said he has not personally seen evidence to act on. “If this recruiting is happening, we have to condemn it,” he said.

Recruiting refugees is a violation of international law, and enlisting children under 15 constitutes war crimes, human rights groups say.

“They told me I would become a soldier and fight the Shabab,” said Ahmed Barre, a bone-thin 15-year-old whose family fled Somalia’s anarchy in 1991, when the central government collapsed. He was born in Dadaab’s camps and has never been to Somalia. “I didn’t want to go. But I was jobless. I wanted to help my family.”

A State Department spokesman, speaking on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the matter, said, “We strongly condemn recruitment in the refugee camps by any party.” Senior U.S. officials, he added, “have stressed” to top Kenyan and Somali government officials “the need to prevent any recruitment in refugee camps.”

Human Rights Watch has also raised concerns about the force, which numbers roughly 2,500.

Once the recruits signed up, their cellphones and identification cards were taken. They never saw the promised money. And they were denied access to their traumatized families, which, fearing deportation, seldom complained to the authorities, local officials and recruits said.

“These people ran away for their dear lives to seek refuge in Kenya,” said Mohamed Gabow Kharbat, mayor of Garissa, the provincial capital. “To recruit them and send them back to the same situation they ran away from, this is terrible.”

Kharbat said that “most of the youths have no parents, no family members to protest on their behalf. And even if they have parents, these are people who are scared of the government security organs. They can never have the confidence to complain.”

The recruitment comes amid fears that Somalia’s Islamist militants could extend their reach into Kenya, Uganda and other neighboring countries. The Shabab has voiced support for al-Qaeda and has attracted jihadists from around the world. The United States and European nations are supporting the pro-Western Somalia transitional government with arms, cash, training and intelligence.

Somali refugees have few opportunities in Kenya, which has imposed strict residency rules and limits on travel, making it difficult for them to find jobs. Many youths are uneducated.

“The Shabab and all other groups have representation here,” said Abdul Khader, 35, a refugee youth leader. “They give a lot of false hopes to the refugees.”

Hassan Mukhtar, 16, was recruited to fight for the Somali government with a promise of $300 a month and a $50 signing bonus.

When he and other recruits did not get their signing bonus, they jumped out of the truck on the way to Manyani.

A Shabab recruiter enticed Mukhtar Awliyahan, 16, by promising him $300 month. He was taken to Somalia and given the nom de guerre “Mukhtarullah” — the One Chosen by God. In January, tired of fighting, he escaped. Today he keeps a low profile in the camp. “They are still recruiting,” he said.

Hezbi Islam, a rival militia, recruited Bare Ali Jama, 19. “I had nothing to substitute for this offer,” said Jama, who joined along with five other refugees. In February, Shabab fighters pushed them out of their stronghold; he fled back to Kenya. Still jobless, he wants to return to Somalia. “I will fight for anybody,” he said.

_____

Washington Post