By Frank Nyakairu DADAAB, Kenya, June 4 (Reuters) – Somalis fleeing war and hunger at home are pouring into neighbouring Kenya at an average rate of 7,000 per month, swelling what is already the world’s largest refugee settlement, U.N. staff said on Thursday.

By Frank Nyakairu DADAAB, Kenya, June 4 (Reuters) – Somalis fleeing war and hunger at home are pouring into neighbouring Kenya at an average rate of 7,000 per month, swelling what is already the world’s largest refugee settlement, U.N. staff said on Thursday.

Eighteen years of civil conflict in Somalia show no sign of abatement, with foreign militants joining Islamist rebels seeking to topple a new government that is the 15th attempt to restore central rule since 1991.

About 80,000 people have died in the last two years alone, while a million Somalis are refugees in their own land, three million need urgent food aid and hundreds of thousands have crossed borders into Djibouti, Ethiopia and Kenya.

“We have been receiving an average of 7,000 refugees (per month) since January and from what they tell us, the major reason why they leave their country is increasing insecurity,” said Anne Campbell, head of the U.N. refugee agency UNHCR’s sub-office in Dadaab, north Kenya.

Located 100 km (60 miles) from the border, Dadaab’s three main camps — Dagahaley, Ifo and Hagadera — are a large settlement of mainly flimsy huts and tents on sandy scrubland.

Set up in 1991, the camp was designed for 90,000 refugees but now houses 275,000, mainly Somalis.

Aid agencies expect this number to keep increasing, and are seeking more space from the Kenyan government.

“We are preparing for a higher influx in mid-June because the rain has made it impossible for those fleeing the current fighting to reach the border easily,” added Campbell.

With high food prices and falling donations due to the global financial squeeze, the U.N. World Food Programme (WFP) warned that supplies for Dadaab could soon be squeezed.

LONG ROAD TO SAFETY

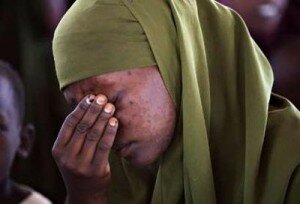

At Dagahaley’s registration centre, new arrivals crammed UNHCR’s offices while others stood for long hours in the scorching sun outside the gate.

“I arrived here eight days ago, I have not been given food or water. I am still waiting to be registered, I don’t know when that will be,” said Asha Aden Ali, a 22-year-old mother of two.

She fled from Mogadishu two weeks ago after insurgents from the al Shabaab militia shelled her home in the outskirts.

“When they attacked, we all ran in different directions. My husband has been missing since,” she said.

“I had to board a truck and come to Kenya.”

Kenya officially closed its borders in 2006 to stop Islamists fleeing after an intervention by Ethiopia’s army.

But like Asha, many Somalis are still making their way across the long, porous and arid border areas.

“I had to wait for a week and a Good Samaritan came and showed me a shortcut to Kenya,” she said.

The United Nations has been in negotiations with Kenyan authorities over re-opening crossing points. But Nairobi maintains that would leave the country open to an influx of refugees and small weapons, which would worsen insecurity.

(Editing by Andrew Cawthorne and Michael Roddy)