NEW YORK — Capt. Richard Phillips knows that when most people think of pirates, they envision Hollywood’s romantic, swashbuckling versions: “Like Johnny Depp,” he says.

NEW YORK — Capt. Richard Phillips knows that when most people think of pirates, they envision Hollywood’s romantic, swashbuckling versions: “Like Johnny Depp,” he says.

Phillips, 54, the first American seaman seized by pirates in two centuries, has a different view of the four armed men who boarded his cargo ship off Somalia a year ago and held him hostage for five days.

“They were desperate guys who didn’t care what happened to anyone else.”

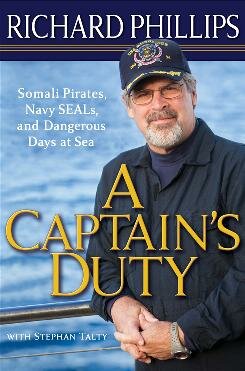

Phillips’ book, A Captain’s Duty: Somali Pirates, Navy SEALS, and Dangerous Days at Sea (Hyperion, $25.99), will be released Tuesday, nearly a year after his dramatic rescue at sea focused attention on modern-day piracy.

On Easter Sunday 2009, after three days alone with pirates in a small lifeboat, Phillips was freed as Navy SEALs shot and killed three of his captors. The fourth is facing trial on a variety of charges in federal court.

Phillips’ book has brought Phillips and his wife, Andrea, an emergency-room nurse in Burlington, Vt., to downtown Manhattan and the Seamen’s Church Institute, which works to improve the lives and working conditions of seafarers.

He was here in December to receive an award — one of many he has gotten in the past year. “He’s a real hero,” says Douglas Stevenson, director of the Center for Seafarers’ Rights, which is part of the Seamen’s Institute. “He put his crew’s safety above his own.”

Has life returned to normal for Phillips now?

“What’s normal?’ Phillips replies. “I’m a merchant mariner,” which means leading a double life: three months at sea, three months at home. “Life wasn’t normal before.”

“We call it our ‘new normal,’ ” his wife, 52, adds, after the awards and speeches and an Oval Office visit with President Obama. (Phillips says the two chatted about sports, leadership and what it’s like to be in the spotlight. “He knew what he was getting in to,” Phillips says. “I didn’t.”)

Phillips, who has yet to decide if he’ll retire or go back to sea, is about to start a three-week book tour. The film rights to his book have been optioned by Kevin Spacey’s production company, which has led to family jokes about Phillips being played by George Clooney, “but only,” he says, “if Andrea gets to play Andrea.”

A Captain’s Duty, written with Stephan Talty, re-creates, day by day, what Phillips, in the Indian Ocean, and his wife, at home in Underhill, Vt., went through a year ago.

Stuck in the ‘shooting galley’

When someone has a loaded AK-47 pointed at your face, you get to know his mood really well, believe me. If he’s happy or annoyed, if his nose itches, if he’s thinking about breaking up with his girlfriend, whatever. You know. — A Captain’s Duty

Phillips and a crew of 19 were on the Maersk Alabama, a 508-foot-long, U.S.-flag-flying cargo ship, off the Somali coast. They were headed to stops in Djibouti and Kenya with 17 tons of cargo, including 5 tons of food aid.

It’s an area that he says has become a “shooting galley” for Somali pirates who’ve learned how to seize ships — not for their cargo but for multimillion-dollar ransoms ship owners have paid.

In two decades as a ship’s captain, Phillips had never been attacked by pirates, although he had some close calls. That changed April 8, 2009.

Four men in a speedboat, armed with AK-47s, were able to overcome the ship’s “pirate cages” (steel bars over the ship’s ladders) and with the use of their own large ladder — “I still don’t know where they got that from,” Phillips says — climbed aboard.

One screamed: “Relax, Captain, relax. Business, just business.”

Most of Phillips’ crew was able to hide aboard the ship, which he says is “like a skyscraper laid flat on the ocean. … There are plenty of places to hide.”

As captain, he began a series of mind games with the pirates: “I wanted to remain an adversary, not just a hostage,” he says. “But it’s a fine line between deceiving your captors and getting a bullet in the forehead.”

He acted “like a dumb captain who couldn’t control his own men” and convinced the pirates that the ship was “broken.” Still on board, he secretly communicated with his crew, who ended up capturing one of the pirates.

That led to what was to be a trade: the captain for the captured pirate. The pirate was released first. The captain wasn’t. Phillips learned a lesson: “Don’t make deals with pirates.”

They were given $30,000 in cash that Phillips had in the ship’s safe for just such emergencies, but they figured they could get a lot more with a hostage. (The pirates demanded $2 million, which they never got.)

And that’s how Phillips, who was not involved in ransom negotiations, ended up with the pirates in an open, 25-foot lifeboat for three days.

Making a break for it

“You have a family?”

The voice was mocking, self-assured. He was the Leader, no question.

“Yeah, I have a family,” I said. I realized with a feeling of panic that I hadn’t said my good-byes to them. I bit down on my lip.

“Daughter? Son?”

“I have a son, a daughter, and a wife.”

Silence. I heard some rustling up near the cockpit. Then the Leader spoke again.

“That’s too bad,” he said. He was trying to rattle me. And he was doing a damn good job of it, actually.

“Yeah, that is too bad,” I shot back. Whatever they did or said, I couldn’t let them know they’d gotten to me.

On his second night in the lifeboat, Phillips thought he saw a chance to escape. He jumped into the ocean and began swimming toward a U.S. warship about half a mile away. But in the moonlight, the pirates caught up with him.

They hauled him in and beat him. “But they were thin guys,” Phillips says, “and they didn’t have a huge amount of power behind their blows. Honestly, my sister Patty hits harder.”

They tied and trussed him “like a deer.” The ropes were so tight, “my hands were starting to swell up like a pair of clown gloves.”

He remembers thinking: “Either I’m getting out of here alive or they are. But not both.”

‘No one ever remembers us’

It seemed like the shooting went on for fifteen minutes, but I’m sure it lasted only a few seconds. I felt raw terror and confusion. …

“What are you doing?” I shouted. “What are you guys doing?”

I thought the pirates were shooting one another, and I was caught in the crossfire. They’d been arguing and it had escalated to gunfire. And now, after days of heat, punishment, and threats, there was complete silence.

All of a sudden I heard a voice. A male American voice. “Are you okay?” it said.

I couldn’t understand who was talking.

“Are you all right?”

“I’m fine,” I said. “But who are you?’

Phillips says he wrote the book as a way of recognizing the merchant marine: “The guys who brought the tanks to Normandy, the bullets to Okinawa, but no one ever remembers us.”

He also wanted to thank his crew, “who did a very good job,” and the Navy SEALs who rescued him, “the real heroes of this story.”

And he says he wanted to “show what we’re capable of when we don’t give up.”

His wife says that as “an emergency-room nurse, I went into my crisis mode,” under an different kind of assault — the news media that surrounded her converted farmhouse in Vermont.

She says, “I never lost faith in Richard, but there were moments of doubt. I know that bad things can happen to good people.”

As for the pirates, Phillips says, “I have no feelings whatsoever. They’re pirates who did what pirates do.”

A year later, he says he’s not bitter or angry: “If I were, I wouldn’t be able to put it behind me. It would still be eating me up.”

His wife adds a story from Vermont, where the 9-year-old daughter of a friend recently asked, “Is Richard still a hero?”

Andrea Phillips answered: “Nah. Been there. Done that.”

____

USA Today