Bartamaha (Nairobi):-The news that some suspected Somali pirates will face trial the United States drew praise this week, but it also raised issues about how pirates should be prosecuted. It may not be so easy to try men from a nearly lawless country for crimes committed halfway around the world.

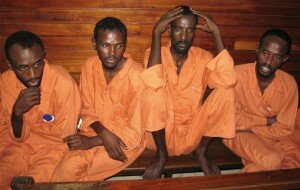

Eleven Somali men appeared in a federal courtroom in Norfolk, Va., early Friday to face indictment on piracy charges in two separate incidents. Officials said five of the men are accused of exchanging fire with the Navy frigate USS Nicholas in the Indian Ocean on March 31. Six others allegedly attacked the amphibious dock landing ship USS Ashland on the Gulf of Aden on April 10.

At least two of the suspects were apparently injured. The Associated Press reports that one of the Somali men had to be carried into court, while another had a bandaged head.

The men were reportedly transferred from the Navy to the Justice Department in Djibouti, and flown to the United States on Thursday.

A New U.S. Resolve

State Dept. Spokesman P.J. Crowley said this week that the decision to try the men in the U.S. should set an example for other nations.

“This is where all countries have to step up just as we are doing and take responsibility for pirates who have attacked their ships and prosecute them to the fullest extent of national law,” Crowley told reporters.

Pirates from Somalia have reaped millions of dollars by holding captured ships and their crews for ransom, but the number of attacks has fallen in the first quarter of this year. The International Maritime Bureau, a watchdog group, says foreign naval patrols in the Gulf of Aden are partly responsible for a significant drop in pirate attacks there from January through March.

The IMB said there were 17 pirate incidents in the Gulf during the first three months of the year, compared with 41 during the same period in 2009. At the same time, though, pirates have increased their attacks in parts of the Indian Ocean that have fewer patrols.

Until recently, Kenya had been prosecuting pirates under agreements with the U.S. and other maritime nations, but Kenya’s foreign minister announced early this month that his country will no longer accept such cases.

Foreign Minister Moses Wetangula said his country’s legal system had been overburdened by the pirate cases, and he said the nations that were supposed to be Kenya’s partners in the prosecutions had not kept their promises to help.

Doug Burnett, an expert on maritime law, says it’s no surprise that the East African country couldn’t keep up with the volume of pirate cases.

“You started out [in Kenya] with a very troubled justice system, then overlaid it with a lot of difficult cases,” he says.

Burnett, a lawyer with the New York-based firm Squire, Sanders & Dempsey, says he welcomes the U.S. decision to take on those prosecutions.

“It’s difficult and tedious and expensive,” he says, but “in this case, I think the U.S. deserves credit for doing the right thing.”

First Case Tough To Prosecute

Right now, the U.S. has only one other pirate prosecution on American soil. It’s the case of Abduwali Abdukhadir Muse, a young Somali who is accused of leading the attempt to capture the cargo ship Maesk Alabama last year.

U.S. Navy snipers killed three of Muse’s companions after they held the ship’s captain hostage in one of the lifeboats. Muse pleaded not guilty in the Maersk case, as well as to charges in two other hijacking cases that prosecutors brought against him in January.

The New York Times reported that prosecutors in the Muse case have written to the judge on behalf of the government and the defense, asking for a “plea proceeding” in May, an indication that the two sides could be negotiating a plea bargain.

Muse’s case illustrates some of the difficulties of bringing cases from Somalia, which has not had an effective national government for nearly three decades. Even Muse’s age is in dispute. Defense attorneys have said that he may have been underage at the time of the crime, but it’s not clear whether there are records that could confirm that.

Merchant sailors, like those in crew of the Maersk Alabama, can be difficult and expensive to assemble as witnesses at a trial, simply because they may be scattered around the globe.

Naval commanders aren’t used to a law-enforcement role, so they don’t always collect evidence that will stand up in court. In many cases, pirates have been able to throw the main evidence against them, their weapons, overboard before navy crews can capture them.

More Nations Stepping Up

The U.S. is not alone in starting more pirate prosecutions, though. Germany is seeking to prosecute ten Somali men who are accused of trying to capture a German merchant vessel a few weeks ago.

The attackers succeeded in boarding the MS Taipan, but the crew had called for help, disabled the ship’s engines and locked themselves in a “safe room.” After the skipper of a nearby Dutch naval vessel learned that the crew was not in harm’s way, he sent commandos to storm the ship and capture the pirates.

The Dutch action was more robust than that of other European Union vessels, which have sometimes let pirate suspects go after confiscating their weapons.

“As it turns out,” says lawyer Burnett, “the Dutch were operating outside of the E.U. area, so the Dutch were under their own rules of engagement. The commander had to determine what to do. He took on the pirates.”

Because the pirates had attacked a German cargo vessel, German authorities have now asked to have the Somali prisoners extradited for trial.

———-

Source:-npr