DAVID MCDOUGALL Special to The Globe and Mail — Mohamed Osman Hassan never questioned his close friend and mentor Bashir Makhtal when in early 2001 he announced plans to leave a well-paid job as an information technologist at CIBC in Toronto for the unlikely sounding, but lucrative, business of hawking used clothing across the volatile Horn of Africa.

DAVID MCDOUGALL Special to The Globe and Mail — Mohamed Osman Hassan never questioned his close friend and mentor Bashir Makhtal when in early 2001 he announced plans to leave a well-paid job as an information technologist at CIBC in Toronto for the unlikely sounding, but lucrative, business of hawking used clothing across the volatile Horn of Africa.

“He saw an opportunity,” said Mr. Hassan, who at the time was finishing a degree in computer science at Brock University. “He’s one of those people that when they see an opportunity, they don’t dither.”

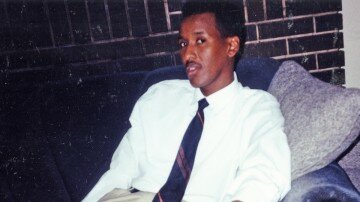

So, in June of 2002, still paying the rent on his Scarborough apartment, Mr. Makhtal, who had immigrated to Canada a decade earlier and once tended his family’s camels over a desiccated African countryside, set off from Pearson International Airport on an extended business trip that would take him to Dubai, Djibouti, Eritrea, Kenya and eventually even back to Somalia.

Today, the Canadian languishes in a tiny, Ethiopian prison, isolated from family, accused and convicted of terrorism, awaiting a grim judgment. What he couldn’t have known the day he stepped on that plane was that a maelstrom of forces – a bloody civil conflict in Somalia, the global campaign against terrorism, a vendetta against his conspicuously political family – were converging to deprive him of his liberty, and perhaps, his life.

For the past two-and-a-half years, Mr. Makhtal has been imprisoned in Ethiopia. For much of that time he was held incommunicado in solitary confinement and denied consular access.

On Monday, he was convicted, but not sentenced, by a civilian court in Addis Ababa on three counts of terrorism-related charges, each of which carries a potential death penalty. He will be sentenced Monday, and Canada, which has been closely monitoring his case, says it will seek clemency if Mr. Makhtal is given a death sentence.

Friends and family say it is all because of his name.

Bashir Ahmed Makhtal was born in 1969 in the Somali region of eastern Ethiopia to a famously political family, the grandson of Makhtal Dahir, a senior member of a separatist movement known as the Ogaden National Liberation Front, which grew out of an ethnic Somali struggle against the military dictatorship of Mengistu Haile Mariam. The ONLF has been locked into a bitter, and at times violent conflict with the Ethiopian government. When his father died, the 11-year-old boy was sent to begin a new life in Mogadishu with his uncle, a Western-educated Somali diplomat.

It was there, under the apple and lemon trees in the large, well-tended courtyard of his new and peaceful home, that he came to know Said Maktal, his younger cousin by three years, who spells his name differently. The two would grow up as brothers.

Now a 36-year-old chemical lab technician living in Hamilton, Ont., by his own accounts a typical Mogadishu kid, spoiled and immature, Said said he was awed by his older, worldly cousin, who had come from afar. “If I remember back then, it was fantastic. Bashir used to tell us amazing stories that we never heard.”

As is customary, Mr. Makhtal, as the older cousin, was the first to go abroad. He first went to school in Italy in 1989 before moving on to Canada two years later, all the while supported by his uncle, who understood the value of a Western education.

Within a year of landing in Canada, Mr. Makhtal was working toward a computer science degree at the DeVry Institute of Technology in Toronto, on a career path that would land him a job at CIBC and BMO.

But Mr. Makhtal never forgot about his family back home. “Bashir always said, ‘I come from a big family,’ ” Said Maktal recalled. ” ‘I am the only one who is outside. I have to work hard to support my family, my nephews, my nieces.’ ” It was in part this same sense of obligation toward his family in Ethiopia that, according to Said Maktal, compelled Mr. Makhtal to set aside his bank job and go into business for himself. He headed back to Africa in 2002, and spent the next few years criss-crossing eastern Africa and, from time to time, returning home to Canada to visit.

By all accounts, Mr. Makhtal’s business ventures – importing used clothes for re-sale in Africa – appeared to be going well.

“He looked fantastic,” recalled Said Maktal after seeing his cousin in early 2005 on one of his periodic return visits to Toronto. “He looked very happy. … Even his clothes, he was never dressing in jeans anymore. He loved wearing suits.”

It was business that prompted Mr. Makhtal’s fateful trip back to his childhood home in Mogadishu in December, 2006.

“Guess what? Guess where I am?” Said Maktal remembers his cousin’s voice crackling over the cellphone. “I’m in our house, the house that we grew up in.”

At the time, Mogadishu was under the control of a grassroots alliance known as the Islamic Courts Union. Much to everyone’s surprise, it had managed in a few short months what countless previous efforts failed to achieve: Mogadishu, perhaps the most violent, unstable place on Earth, had been pacified.

But Mr. Makhtal’s situation was more precarious than he realized. While for ordinary Somalis, Mogadishu was experiencing an almost unknown period of stability, alarm bells were going off in Washington.

In the post-9/11 world, Somalia had become a lesser-known frontier of the war on terrorism. Of particular concern was the rise to prominence within the Islamic Courts of certain figures with suspected links to terrorist organizations. Something had to be done, and it was neighbouring Ethiopia that was going to do it, invading Somalia with a tacit green light from the United States. While Mr. Makhtal spoke with his cousin back in Hamilton, rumours of an impending Ethiopian action were already circulating in the news.

“If your business is done,” Said Maktal recalled telling his cousin, “please get the hell out of there.” It would be close to a year before they spoke again.

Mr. Makhtal knew enough about his family legacy to know that he didn’t want to fall into the hands of the Ethiopians. But on the day he was scheduled to fly out of Mogadishu for Nairobi, it was already too late. Commercial flights had been cancelled.

Left with no other choice, Mr. Makhtal, along with scores of others, fled to the Kenyan border where he planned to cross by road. Instead, he would be scooped up in an operation ostensibly aimed at capturing senior leaders of the ICU.

While difficult to verify independently, here’s what happened next according to a combination of sworn affidavits from former detainees collected in Kenya, accounts of court testimony from Mr. Makhtal documented by Canadian officials and interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch: On Dec. 31, just hours away from the border, Mr. Makhtal hired a car along with seven others and drove to the Liboi transit centre, where he attempted to cross into Kenya on his Canadian passport. All eight of the passengers were immediately detained.

After being interrogated for several days at a regional police headquarters about their involvement with the ICU, Mr. Makhtal and other prisoners were transferred to a Nairobi police station where they were further interrogated by the Anti-Terrorism Police Unit, a U.S.-funded branch of the Kenyan police force.

In apparent violation of Kenyan law, every effort was made to hold the prisoners incommunicado and longer than the 14 days permitted without charge. That was when alarmed members of the regular police force alerted a local human rights group.

“Our contacts within the Kenyan police, very high up there, told us this has nothing to do with them,” said Al-Amin Kimathi, chair of the Nairobi-based Muslim Human Rights Forum, which managed to gain accesses to some of the prisoners, who included a pregnant women and a 9-year-old child.

Mr. Kimathi’s organization had hired lawyers and was preparing a series of habeas corpus petitions when the prisoners disappeared.

In the early hours of Jan. 20, the prisoners, including Mr. Makhtal, were called out of their cells and transported to the international airport in Nairobi where, according to Human Rights Watch, they were handcuffed, blindfolded and put on a chartered aircraft headed back to Mogadishu.

It was the first of three flights that in January and February of 2007 would transfer at least 80 prisoners, including Kenyan, U.S., British and Swedish nationals, to jails in Ethiopia, where many said they were interrogated by U.S. intelligence.

But Mr. Makhtal’s case was different. It was all about his family, and a birthright that left his name on the executive committee of the ONLF, even though friends and family claim he was never involved with the group in any way.

Once in Ethiopian custody, Mr. Makhtal disappeared.

Back in Canada, Said Maktal, a father of three, began the tireless task of bringing his cousin’s case to the attention of the Canadian government, first convincing Foreign Affairs officials to acknowledge that he was even in Ethiopia and later sending petitions to the Prime Minister, even retaining the Toronto-based human rights lawyer, Lorne Waldman.

“He would have done the same thing for me,” said Mr. Maktal. “Actually, he would have done it for anyone.”

It wasn’t until earlier this year that his efforts began paying off, in part because of the involvement of federal Transport Minister John Baird who took an interest in the case after hearing from the Somali community in his riding.

In January, Mr. Makhtal was transferred out of solitary confinement and his case moved to a civilian court where, in March, he was formerly charged for his alleged involvement in the ONLF.

But human rights groups and legal experts have criticized the trial for being little more than a kangaroo court, which has repeatedly failed to produce credible witnesses or evidence linking Mr. Makhtal to the ONLF, and has refused to accept evidence, including a letter form the movement’s top brass, stating that Mr. Makhtal was not a member.

“Everyone we spoke to who observed the trial,” said Mr. Waldman, “was convinced that they had absolutely no case, and yet he was convicted, which is really just a testimony to the unfair legal system.”

Foreign Affairs Minister Lawrence Cannon said in a statement yesterday that consular officials have visited Mr. Makhtal as recently as July 28, and that his case remains a priority for the Government of Canada.

“The government of Canada has sought assurances from the government of Ethiopia that the death penalty will not be applied in this case. We will seek clemency for Mr. Makhtal if the death penalty is imposed.”

But until Mr. Makhtal is released, his cousin, pointing out his newly greyed hair, says he won’t be able to rest, even though it’s taking a heavy toll.

“Two nights ago, my wife told me, ‘You’re not the

same [person] that I married.’ That kills you. … “

“But again, you look at the other side and it’s like the whole world is against your cousin, and you’re the only person he has.”

WHAT IS THE ONLF

The Ogaden National Liberation Front describes itself on its website as a “grassroots social and political movement” that serves as an “advocate for and defender of” Somalis in Ogaden, a region of eastern Ethiopia with a large ethnic Somali population, against Ethiopian regimes.

Founded in 1984 by members of a variety of ethnic Somali liberation groups, it can also be described as a separatist rebel group fighting to make Ogaden an independent state.

Its main tactics include countering government influence in the region and using violent force, including kidnappings and bombings. The ONLF is believed to be responsible for the deaths of thousands of government forces.

ONLF supporters say the group does not use bombing as a tactic and has a policy of deliberately not targeting civilians in its military operations. While some experts consider the ONLF’s activities terrorism, the U.S. State Department does not include the OLNF on its Foreign Terrorist Organization list and the group is not on similar lists maintained by the European Union and Britain.

In 1991, the ONLF joined the political process, and performed well in regional parliamentary elections. The group’s political wing later merged with another political party to form the Somali People’s Democratic Party, which remains a powerful political force in the region.

The ONLF has instigated ambushes and guerrilla-style raids against Ethiopian troops since its inception, and has kidnapped foreign workers presumed to be agents or supporters of Ethiopia’s government. It has launched attacks on Ethiopian military convoys, and it has been accused of bombings in Ethiopia’s capital.

A particularly fierce dispute has long simmered between the central government and ONLF over the presence of energy companies in the region; ONLF insists it will not allow the exploration of oil and gas in the area until the region gains independence, and threatens foreign companies that try.

Source: Council on Foreign

Relations