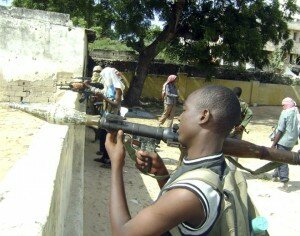

Fighting in and around the presidential palace in Mogadishu and the strategic areas in the vicinity of the Somali capital’s international airport quashed hopes this week that the Transitional National Government (TNG) of Somalia is ready to placate its militant Islamist foes. TNG political heavyweights’ failure to accommodate the demands of the militant Islamists to institute an Islamist state in Somalia is the most dangerous sign of the TNG’s weakness. Without domestic consensus, Somali militias tied to political groups resort to violence to impose their ideological will.

Fighting in and around the presidential palace in Mogadishu and the strategic areas in the vicinity of the Somali capital’s international airport quashed hopes this week that the Transitional National Government (TNG) of Somalia is ready to placate its militant Islamist foes. TNG political heavyweights’ failure to accommodate the demands of the militant Islamists to institute an Islamist state in Somalia is the most dangerous sign of the TNG’s weakness. Without domestic consensus, Somali militias tied to political groups resort to violence to impose their ideological will.

This observation leads in two possible directions. The first is that the repeated military setbacks of the Somali government forces have starkly illustrated the inability of Western powers, in spite of open and unconstrained support for the TNG, to influence events in war-torn Somalia. The meddling of neighbours fearing an Islamist takeover in Somalia will undoubtedly intensify, complicating matters further. Even so, Ethiopia, the most powerful nation in the Horn of Africa, after a series of military setbacks in Somalia, will be loath to be dragged back in.

The second prognosis is that all sides must yield ground if the Al-Mujahideen Al-Shabab (Youthful Fighters), the main armed opposition group in Somalia is to leave violence behind.

The key question that nobody in the West cared to ask himself or herself is why democracy Western-style offers little to attract the vast majority of Somali people. That, in turn, suggests that militant Islam does have a hold on Somali society.

Not only is Somalia a failed state, but it is also a haven of terrorists. Somalia’s neighbours are increasingly concerned that the escalating violence in Somalia will spill over into their territories. Somalia’s neighbours have a common interest in fighting terrorism. They also have the full backing of Western powers. Yet they are collectively incapable of containing the rapidly deteriorating situation in Somalia. The failure of the combined forces of the TNG and its African allies to defeat the Shabab and other militant Islamist groups actually provides yet another barbarous illustration of the West’s inability to change the fortunes of the ill-fated TNG. And even worse, it proves the paucity of the West’s formidable arsenal when it comes to punishing militant Islamists that adamantly refuse to bend to the West’s will.

To be fair, the West is fighting a war by proxy in Somalia using its African allies as pawns. Militants of Al-Shabab have shown once again that they can kill government lackeys across Somalia with impunity. What they have not proven yet, is that they can actually usurp power by storming the presidential palace in Mogadishu.

Whether that happens remains to be seen. This week they have come perilously close to doing so. The TNG, its African allies and their Western backers all hope against hope that this week’s attacks on strategic positions in Mogadishu are a desperate last throw of the dice by hardened Islamist militants. The facts on the ground demonstrate beyond doubt that the militant Islamists are not losing support in Somalia. The TNG has been weakened militarily and politically, some would argue mortally wounded.

It is hard to imagine at this point that the militant Islamists would be tempted to take the hard decision to drop violence. Neither are they likely to take the equally hard decision to talk peace with the TNG. Why should they?

The TNG appears to be a spent force. Somalia is now on its way to becoming a Taliban-like state. That may not be a nice thought as far as Somalia’s neighbours and their Western allies are concerned. But it is perhaps no worse than the prospect of a desperate TNG in its death throes hanging on for dear life to power by the help of a permanent Western and neighbouring African military presence à la Afghanistan.

On the political front, too, the TNG suffered a crippling blow this Ramadan. The secularists of Somalia have surely lost ground. The militant Islamists argue that the Somali people have neither invited nor welcomed the intrusion of foreigners — neighbouring African and Western — in their internal political affairs.

The fact that the international community has used every measure and threat and still failed to influence the outcome of the violence in Somalia gives little hope to those in the TNG who are looking for overseas pressure to try and dislodge the militant Islamist forces from Mogadishu.

Lingering social discontent, the intensification of the Islamist insurgency and political deadlock are a combustible combination both for Somalia and its neighbours. The longer Somali politicians wrangle over who is to run the country and the more apparent it becomes that the West cannot provide some hand-holding for the TNG, the more frustrations among the long-suffering Somalis will explode into uncontrollable political chaos. The political impasse aggravates the crisis of governance in Somalia. Yet the flare-up could easily be contained if the TNG relinquishes power amicably. This last and very plausible political option is always a far cry from the frightening scenarios envisaged by the doomsayers.

___

Al Ahram