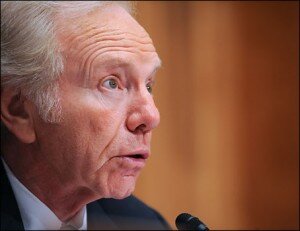

In the space of roughly three years, Connecticut Sen. Joe Lieberman (I) has done the following:

In the space of roughly three years, Connecticut Sen. Joe Lieberman (I) has done the following:

1. Strongly supported the war in Iraq, allowing then President George W. Bush to cite him as an example of the bipartisan support for the conflict.

2. Lost a Democratic primary for his seat only to run and win as an independent thanks to the fact that Republicans did not field a serious candidate against him.

3. Endorsed the 2008 presidential candidacy of Arizona Sen. John McCain (R) and delivered a speech at the Republican National Convention in which he called of President Obama a “gifted and eloquent young man” before adding: “Eloquence is no substitute for a record.”

4. Almost single-handedly brought down the idea of a Medicare buy-in compromise in the health care bill, a move that virtually ensures any sort of government-run plan is dead.

What gives? How has Lieberman exerted so much influence over a party to which he now seems to have only the most tangential connections and loyalty?

There are three answers to that question: basic math, the “hail fellow well met” attitude of the Senate and the “80 percent friend” theory.

First, the math.

After Lieberman lost the 2006 Democratic primary but won the general election running as an independent, he returned to a Senate where Democrats held 50 seats without him and 51 seats with him. Given that Bush was president at the time, if Lieberman had not caucused with Democrats, Republicans would have controlled the chamber.

Fast forward to earlier this year when Lieberman’s support for McCain had many in the party’s base insisting that the Connecticut Senator be banned from caucusing with Senate Democrats. Without Lieberman, Democrats had 59 seats. With him, they had 60 and, theoretically, a filibuster-proof majority.

In both instances, Lieberman benefited from the fact that Democrats — led by Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (Nev.) — needed him more than he needed the party. Lieberman knew that he could say or do whatever he wanted (within some bounds) and not have to worry about being thrown from the caucus.

“If we were at 45 or 55 [seats], no one would care [about Lieberman],” said one senior Democratic Senate strategist. “He’d be out on his ass.”

The second major reason Lieberman has been allowed to exert as much influence as he has is explained by the nature of the Senate — a clubby atmosphere that largely protects its own.

Lieberman, first elected in 1988, was extremely well-regarded within his own caucus earlier this decade — even as his ardent backing of the Bush Administration’s policy in Iraq had begun to transform him into a man apart.

One senior Democratic consultant said that after his 2006 race, there was a “huge amount of goodwill and sympathy and genuine affection” from fellow Senators to Lieberman.

(It’s also worth noting that all politicians live in fear of being ousted by a wealthy challenger running a single-issue campaign so Lieberman’s loss was undoubtedly deeply felt by many of his colleagues.)

By all accounts, that warm regard for Lieberman has largely worn off in the intervening years as the Connecticut Senator has grown increasingly willing to break with his party on major issues.

The final reason that Lieberman remains such a power player is that, for the past several years, Senate Democrats have adopted Ronald Reagan‘s famous maxim that “my 80 percent friend is not my 20 percent enemy” when it comes to Lieberman.

“Because he is there often enough for other key votes, leadership must deal with him and he knows he can use his leverage for his own selfish purpose or ego,” said Penny Lee, a former deputy chief of staff to Reid. Lee added that Lieberman sided with Democrats on critical votes on the budget and Medicare in 2008.

A look at National Journal’s vote ratings from 2008 show that Lieberman — while clearly a centrist — was not by the most conservative Senator caucusing with Democrats. Lieberman ranked as more liberal than 57.5 percent of the Senate last year, a score that put him to the ideological left of six Democrats: Ben Nelson (46.7), Mary Landrieu (53.2), Mark Pryor (55), Max Baucus (57.3), Kent Conrad (57.3) and Claire McCaskill (57.3).

While Lieberman may not be the most conservative, his style — seen by critics as a willful flaunting of his opposition to major Democratic majorities — may make his “80 percent friendship” (or, more accurately, his “57.5 percent friendship”) less valuable in the eyes of Democrats.

“I used to buy into the ‘Joe’s with us more than against us,’” said one prominent Democratic consultant. “Now I think we are weak and should punish him in every possible way.”

The question of punishment remains a hot-button topic — particularly among the party’s liberal netroots. The most obvious form of punishment would be to take away Lieberman’s chairmanship of the Homeland Security Committee but that move would almost certainly drive the Connecticut Independent out of the Democratic caucus and eliminate the party’s filibuster proof majority.

Ultimately, the decision will come down to Reid, who has huge amounts at stake in the 2010 election with polls showing him trailing several unknown Republican opponents. While Reid has largely resisted the calls from liberals to punish Lieberman in the past, he may not be in a position to do so any longer.

Source: Washingtonpost