Bartamaha (Shelbyville):- Teenagers in T-shirts and shorts raise money for their high school marching band outside of Walmart. Pudgy shoppers walk a 19th-century brick-fronted Square. Beauty-shopped coiffed women join their men in a traditional wooden-pewed church – and a woman in the conservative robes of an African Muslim drives through town as the movie’s soundtrack plays the strains of “I am a poor, wayfaring stranger.”

Bartamaha (Shelbyville):- Teenagers in T-shirts and shorts raise money for their high school marching band outside of Walmart. Pudgy shoppers walk a 19th-century brick-fronted Square. Beauty-shopped coiffed women join their men in a traditional wooden-pewed church – and a woman in the conservative robes of an African Muslim drives through town as the movie’s soundtrack plays the strains of “I am a poor, wayfaring stranger.”

Kim Snyder’s new documentary,“Welcome to Shelbyville,” quickly establishes the jarring presence of Somali Muslims in the old-fashioned Southern town of about 19,000 that lies 65 miles north of Huntsville.

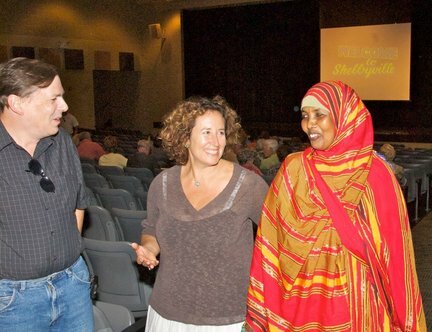

“I want to tell stories that show regular folks coming together around really tough issues,” Director and producer Snyder said Sept. 12 as she introduced the U.S. premiere of the documentary at a screening for local leaders and those who are in the film.

The documentary will be screened publicly in Shelbyville Oct. 17, at 2 p.m., in the high school auditorium, and nationally on PBS in the spring.

“Shelbyville is an exemplary and wonderful place,” Snyder said. “I think you are going to foster more understanding and healing around this issue.”

The healing has already begun, she said. Snyder had just returned from traveling with a U.S. State Department delegation to Nigeria, where “Welcome to Shelbyville” was shown for the first time.

“People in Africa sat and sobbed,” Snyder said. “There was such identification – and these are people living in a place where people get killed over these kinds of things.”

‘Animals’ in town

There were no murders, but plenty of anger and confusion for city residents when, over the past five years, some 500 legal refugees from Somali moved to town to work at the chicken plant.

“There was a perception that the Somalis were not nice or easy to get along with like the Hispanics were,” says Bedford County Mayor Eugene Ray in one of his appearances in the film. He is referring to the influx of Hispanic immigrants to the area in the 1980s and ’90s.

“The Somalis were seen as demanding and aggressive,” Ray says in the film. “But, hey: Maybe a year ago they were fighting for food. They had to be aggressive.”

Brian Mosely, a reporter for the Shelbyville Times-Gazette, remembers witnessing a Somali man shove a woman toward the desk of the driver’s license window, demanding she be given a license.

“There was a lack of cultural orientation when they were brought over here,” says Mosely in the film. “We had a serious, serious culture clash here.”

Angry voices on the Internet and talk radio decried the immigrants.

“We might as well give the country over to these animals,” opined a typical remark posted online that commented on the award-winning series Mosely wrote about the Somalis.

Mosely could understand the suspicions – Shelbyville residents, even emergency officials, had no way of communicating with the Somalis, and going online for information didn’t help.

“They would go home and Google ‘Somali,’ and what comes up?” said Mosely, referring to reports of violence and extremism in the chaotic country. “That was scaring them.”

The film follows local residents over the course of 2008-09 as they work through their fear and begin to find ways to communicate with the new immigrants. The city’s Welcoming Tennessee Initiative has become a model for the program supported by the Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition.

Southern integration

“Most folks think you’re plumb mean,” says outspoken caterer Beverly Hewitt in the film, meeting with a Somali woman who has agreed to open her home to the visitors. “They think you’re going to come over here and blow us up.”

“Bad news, I don’t like bad news,” says Hawo Siyad, a Somali woman profiled in the film. “I like to talk to all people, but they don’t like to talk to me.”

That kind of honesty is what helps make the film both compelling and valuable, Snyder said. And the determination of residents to find a way to live together is what makes it unforgettable. Produced by the San Francisco-based Active Voice and Chicago-based Because Foundation, the film was also screened at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C.

That meaningful integration can often happen better in a small town than in a city doesn’t surprise Snyder.

“In a smaller city, people are living in relationship,” Snyder said. “They are not transient; they have to work through it. In bigger places, you can stay separate for ages.”

“I was impressed with the ability of people to speak their minds without it escalating into a really negative place,” Snyder said. “These are people speaking about what they think is the right thing, about values, about what really matters.”

———————————————

Source:-The Huntsville Times