Carol Rosenberg at the Miami Herald broke the news on Saturday that 12 prisoners have been released from Guantánamo. The news followed hints in the Washington Post on Friday that six Yemenis and four Afghans were set to leave, but Rosenberg — and the East African media — reported that the men had already been freed and that two Somalis were also released. I’ll be writing soon about the Afghans and the Yemenis, but for now I’d like to focus on the stories of the two Somalis: Mohammed Sulaymon Barre and Ismail Mahmoud Muhammad (identified as Ismael Arale).

Carol Rosenberg at the Miami Herald broke the news on Saturday that 12 prisoners have been released from Guantánamo. The news followed hints in the Washington Post on Friday that six Yemenis and four Afghans were set to leave, but Rosenberg — and the East African media — reported that the men had already been freed and that two Somalis were also released. I’ll be writing soon about the Afghans and the Yemenis, but for now I’d like to focus on the stories of the two Somalis: Mohammed Sulaymon Barre and Ismail Mahmoud Muhammad (identified as Ismael Arale).

Rosenberg reported that the two men “were processed by the Somaliland government and then released to rejoin their families in Hargeisa,” the capital of “the breakaway region in northern Somalia that has its own autonomous government.” She added, “The United States does not recognize the government in Somaliland and there were no official statements on how Arale and Barre arrived there. A local newspaper, the Somaliland Press, said they arrived aboard a jet provided by the International Committee of the Red Cross, suggesting that the United States had released the men to the Red Cross in a third country.”

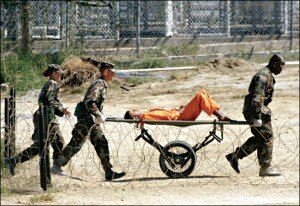

As President Obama attempts to close Guantánamo, with the administration recently announcing its intention of purchasing a prison in Illinois to hold some of the prisoners, the release of these two men — as with the overwhelming majority of releases from Guantánamo — yet again demonstrates how hysterical and unsubstantiated are Republican claims that Guantánamo is full of hardcore terrorists, as their stories demonstrate.

Seized in Pakistan: Mohammed Sulaymon Barre

Mohammed Sulaymon Barre, who was 37 years old at the time of his capture, was one of the first men to be seized in the “War on Terror.” As I explained in my book The Guantánamo Files, he had been living in Pakistan as a UN-approved refugee since fleeing his homeland during its ruinous civil war in the early 1990s, and was seized at his home in Karachi on November 1, 2001 “by police and intelligence agents who had made two previous visits to check his papers, and who seem, therefore, to have seized him on this third occasion because they were looking for easy targets to hand over to the Americans.”

As I also explained in The Guantánamo Files:

Barre worked from his home as the Karachi agent for the Dahabshiil Company, a Somali organization with branches around the world, which provides essential money transfer operations for the Somali diaspora. According to the Americans, Dahabshiil was “closely related to al-Barakat, a Somali financial company designated as a terrorism finance facilitator,” [which had been added to a U.S. terrorism watch list and had its assets frozen]. Barre said that he knew nothing about this allegation, pointing out that his job only involved making small transactions on behalf of Somalis living in Pakistan.

In fact, as was noted in a report in 2004 [for a UN conference on Trade and Development], the enforced U.S.-led closure of money transfer operations with suspected links to terrorism was “disastrous for Somalia, a country with no recognized government and without a functioning state apparatus. After the international community largely washed its hands of the country following the disastrous peacekeeping foray in 1994, remittances became the inhabitants’ lifeline. With no recognized private banking system, the remittance trade was dominated by a single firm (al-Barakat).” Crucially, the report added that, although the U.S. authorities closed down al-Barakat in 2001, labeling it “the quartermasters of terror,” only four criminal prosecutions had been filed by 2003, “and none involved charges of aiding terrorists.”

Nevertheless, the authorities at Guantánamo — operating in a bubble of terror-related allegations that largely bore no relation to the realities of the outside world — had no time for Barre’s protestations of innocence. “I am convinced that your branch of the Dahabshiil company was used to transfer money for terrorism,” the presiding officer of his tribunal at Guantánamo told Barre in 2005. “What I am trying to find out is if you think maybe there were some people that were using your company and using your branch to transfer money, or whether you were just totally not paying attention.”

A year later, as the BBC reported in August 2006, al-Barakat had been removed from the U.S. watchlist of terrorist organizations. The report explained that al-Barakat had been included on the watchlist because U.S. intelligence analysts thought it had been used to finance the 9/11 hijackers, but the 9/11 Commission had investigated the claim and had found it baseless. In February 2009, in a report for the Washington Post, Peter Finn noted that, in the allegations against Barre at Guantánamo, Dahabshiil’s alleged ties to al-Barakat had been dropped by 2006, although even then the taint of the allegation was not entirely removed.

In a letter to the Post, an attorney for Dahabshiil was obliged to point out that the firm has “never been the subject of any investigation in relation to alleged terrorist funding” and that it “has no involvement whatsoever with money laundering or the funding or of terrorist organizations and … places the highest importance on money laundering compliance.” As the Post noted ruefully, “Dahabshiil should have been given an opportunity to comment for the article.”

Shorn of this central allegation, it is no wonder that, as Barre’s lawyers explained in a court filing in connection with his habeas corpus petition, the allegations against him have “varied dramatically.” In 2006, for example, presumably through a false allegation coerced from some other prisoner, the authorities claimed that he was not in Pakistan in 1994 and 1995 — despite the existence of UN papers documenting his meetings in Pakistan in those years — but was actually working in Osama bin Laden’s compound in Khartoum, Sudan, an allegation so worthless that his lawyers described it as “implausible and unsubstantiated.”

According to Emi MacLean of the Center for Constitutional Rights, which represents Barre, most of his problems at Guantánamo stemmed from his opposition to the regime at prison, and his involvement in several hunger strikes. “If you were detained for seven years without charge and any fair process, you might be engaged in activities that would be considered disciplinary violations that are really protests for your detention,” she said.

The truth, as Barre himself noted at his tribunal in 2005, was that “A lot of interrogators said to me that … a lot of mistakes were made and they must be corrected. They told me many times that I am here by mistake.” Sadly, this was not enough to prevent him from suffering in Guantánamo, and also in U.S. custody in Bagram before his transfer to Guantánamo in 2002, when, as he explained in his tribunal:

They interrogated me and one of the interrogators told me I was from al-Wafa [a Saudi charity that was also regarded with suspicion by the U.S. authorities] and I needed to confess to that. You have no choice. I told them it wasn’t true. They pressured me. They whispered something then spoke to the guard. The guard came in, grabbed me by my neck and threw me. He took me in a bad way to isolation. All my blankets, except one, were taken from me. It was freezing cold. They didn’t feed me lunch and sometimes they didn’t feed me twice. At night it is very cold and if you don’t eat dinner it gets colder. This torture lasted fifteen to twenty days. My feet and hands were swollen. I wasn’t able to stand because I was in so much pain. I asked for treatment and an interrogator brought a nurse and asked if I wanted treatment. They told me they could cut my legs to stop the pain. They did this so I would confess to the accusations that I didn’t do. Nothing happened. After the torture ended, I met another interrogator who told me injustice was done to me and I didn’t have anything to do with this. He said he would do a report so I could go home. He told me I would be released. Suddenly, I was taken back to Kandahar and then to Cuba.

Seized in Djibouti: Ismail Mahmoud Muhammad

Unlike Mohammed Sulaymon Barre, Ismail Mahmoud Muhammad was one of the last prisoners to arrive at Guantánamo, one of just six men flown to the prison after the arrival of 14 “high-value detainees” in September 2006. Identified by the Pentagon as Abdullahi Sudi Arale, he arrived with little fanfare in June 2007, and, as I explained in an article in September 2007:

Possibly … his arrival was little trumpeted because it involved the deliberately under-reported “War on al-Qaeda” in the Horn of Africa, and because the administration had very little information to offer about him. In almost questioning terms, Arale was described as a “suspected” member of “the al-Qaeda terrorist network in East Africa,” who served as “a courier between East Africa al-Qaeda (EAAQ) and al-Qaeda in Pakistan.”

In a press release, the DoD added that, after returning to Somalia from Pakistan in September 2006, he “held a leadership role in the EAAQ-affiliated Somali Council of Islamic Courts (CIC),” and noted, with distressing vagueness, that there was “significant information available” to indicate that Arale had been “assisting various EAAQ-affiliated extremists in acquiring weapons and explosives,” that he had “facilitated terrorist travel by providing false documents for AQ and EAAQ-affiliates and foreign fighters traveling into Somalia,” and that he had “played a significant role in the re-emergence of the CIC in Mogadishu.” Unmentioned, of course, was the subtext of the situation in Somalia: the role of the CIC in returning some semblance of order to one of the world’s least-governed countries, and the US government’s use of Ethiopia as a proxy army in yet another secret, dirty war.

It took some time for the truth about the Pentagon’s “distressing vagueness” to be explained, in part because the U.S. authorities released no further information about him, and, in two and a half years, do not appear to have conducted a Combatant Status Review Tribunal, to ascertain whether he was correctly designated as an “enemy combatant.” However, when Reprieve, the legal action charity whose lawyers represent dozens of Guantánamo prisoners, became involved, another narrative emerged, in which Muhammad not only had no connection to al-Qaeda, but was, in fact, “an English teacher and centrist political activist.”

Born in Mogadishu in 1970, Muhammad had remained in the capital throughout the civil war of the 1990s until the security situation deteriorated to such an extent that he moved north to Somaliland, establishing the first English school in the new country, and working as a journalist. In 1998, he traveled to Pakistan, where he studied English Literature at the International Islamic University, and became, as Reprieve described it, “a respected leader of the Somali community in the country.”

When his father died, he moved back to Mogadishu, “where the rule of the Union of Islamic Courts had brought relative stability to the war-torn capital,” but at the end of 2006, when, backed by the U.S., the Ethiopian Army invaded, he moved north one more. Opposed to the Ethiopian invasion, he was asked, “as a respected member of the community … to attend a conference in Eritrea aimed at organizing a political campaign” to ensure that the Ethiopians left.

It was while he was on his way to this conference that he was seized by local police in Djibouti, “apparently at the behest of the Americans.” Handed over to the U.S. military, he was taken to Camp Lemonier, the US military base that played a key role in American interference in the Horn of Africa, where other prisoners have been held, possibly including an unknown number of “ghost prisoners.” There, as Reprieve explained, “he was held in a shipping container and interrogated by Americans.”

Compared to Mohammed Sulaymon Barre, Ismael Mahmoud Muhammad was fortunate that his wrongful imprisonment lasted for only two and a half years, but as the eighth anniversary of the opening of Guantánamo approaches, the release of these two men — neither of whom was cleared until the Obama administration’s inter-agency Task Force began its deliberations this year — demonstrates, yet again, that, when it comes to undoing the shameful legacy of Guantánamo, much work still remains to be done.

Andy Worthington is the author of The Guantánamo Files: The Stories of the 774 Detainees in America’s Illegal Prison (published by Pluto Press), and the co-director (with Polly Nash) of the documentary film “Outside the Law: Stories from Guantánamo.” He maintains a blog here.

www.huffingtonpost.com