![]() By JEFFREY GETTLEMAN — NAIROBI, Kenya — Somalia is once again a raging battle zone, with jihadists pouring in from overseas, preparing for a final push to topple the transitional government.

By JEFFREY GETTLEMAN — NAIROBI, Kenya — Somalia is once again a raging battle zone, with jihadists pouring in from overseas, preparing for a final push to topple the transitional government.

The government is begging for help, saying that more peacekeepers, more money and more guns could turn the tide against the Islamist radicals.

But the reality may be uglier than either side is willing to admit: Somalia has become the war that nobody can win, at least not right now.

None of the factions — the moderate Islamist government, the radical Shabab militants, the Sufi clerics who control some parts of central Somalia, the clan militias who control others, the autonomous government of Somaliland in the northwest and the semiautonomous government of Puntland in the northeast — seem powerful enough, organized enough or popular enough to overpower the other contenders and end the violence that has killed thousands over the past two years.

Somalia analysts say the main event, the government versus the Shabab, will drag on for months, fueled by outside support on both sides. The United Nations and Western countries see the transitional government, however feeble, as their best bulwark against piracy and Islamist extremism in Somalia, and are pumping in hundreds of millions of dollars for the government’s security. At the same time, the Shabab are kept afloat by an influx of weapons and fighters, much of it reported to be flowing through neighboring Eritrea.

The Shabab, more than anyone else, have succeeded in internationalizing Somalia’s conflict and using their jihadist dreams to draw in foreign fighters from around the globe, including the United States. The Shabab, whose name means youth in Arabic, are a mostly under-40 militia who espouse the strict Wahhabi version of Islam and are guided, according to American diplomats, by another, better-known Wahhabi group: Al Qaeda.

The Shabab, more than anyone else, have succeeded in internationalizing Somalia’s conflict and using their jihadist dreams to draw in foreign fighters from around the globe, including the United States. The Shabab, whose name means youth in Arabic, are a mostly under-40 militia who espouse the strict Wahhabi version of Islam and are guided, according to American diplomats, by another, better-known Wahhabi group: Al Qaeda.

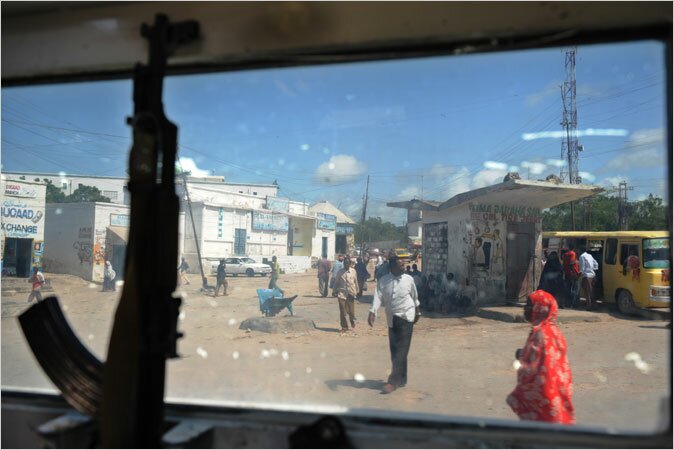

Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah, the top United Nations envoy for Somalia, said that there were now several hundred foreign jihadists fighting for the Shabab. He noted that they were “more motivated, better organized and better trained†than typical Somali street fighters, who tend to be teenagers paid a few dollars a day to charge blindly into battle with rusty Kalashnikov rifles. These young combatants know as much about military tactics as they do about school, which is not a lot. Class has essentially been out for the past 18 years, since Somalia’s central government collapsed.

But the Shabab have limitations, too. In the past few weeks, the Shabab and their allies all but seized Somalia’s capital, Mogadishu, and sealed the escape routes out of the city. In the end, though, they were unable to overrun those very last, but strategically vital, areas the government still controls, like the port, the airport and the hilltop presidential palace.

The new Shabab overseas recruits have imported to Somalia the tricks of Al Qaeda’s trade, like remote-controlled explosives and suicide bombs. But as Iraq and Sri Lanka have shown, insurgents need more than suicide bombs to take over a country. They need overwhelming force, or a persuasive ideology and governing strategy, all of which the Shabab currently lack. The only role that seems fit for them right now is that of spoiler.

“The Shabab can’t govern,†said Hassan Gabre, a retired engineer in Mogadishu. He said the Shabab were simply part of Somalia’s industry of violence, trying to defend “the anarchy regime.â€

Shabab clerics are quick to put their austere version of Islam into effect in the territory they seize, recently amputating the hand of a convicted thief and then dangling the lifeless, bloody results in front of a shocked crowd in Kismayo, a port town in southern Somalia. But this may be just a gruesome side show.

Mr. Ould-Abdallah spoke of a “hidden agenda†and suggested that the real reason the Shabab and their allies were in control of Kismayo was a confluence of sinister business interests like gun-running, human smuggling and the underground charcoal trade.

“There’s an economic dimension here,†he said.

It was not always like this. The Shabab were a crucial part of a functioning mini-government in 2006, when an alliance of Islamic courts briefly controlled much of south-central Somalia. The Shabab’s controversial religious policies were tempered then by moderate Islamists, who delivered services like neighborhood clean-ups and community policing, and as a result the whole Islamic movement won grass-roots support. In the end, the experiment lasted only six months, until Ethiopian troops, backed by American military forces, invaded and drove the Islamists underground.

That intervention failed. The Islamists returned as a fearsome guerrilla force and the Ethiopians pulled out this January, setting Somalia more or less back to where it had been in 2006, with 17,000 people killed in the process (according to Somali human rights groups). Moderate Islamist leaders then took over the transitional government, nominally protected by 4,300 African Union peacekeepers.

But no one is especially well liked in Mogadishu these days, not even the peacekeepers, who may have the most dangerous peacekeeping mission of all. Many Somalis turned against them after a deadly episode in February when a roadside blast hit an African Union truck and the peacekeepers responded by firing wildly into a crowded street. According to Somali officials, the peacekeepers killed 39 civilians, though the African Union said that the true figure was much lower and that the people had died in a cross-fire. Radical Islamists are now calling the African troops “bacteria.â€

All this could be an opportunity for the transitional government. After all, the new president, Sheik Sharif Sheik Ahmed, rose to popularity as a neighborhood problem solver, best known for helping free kidnapped children.

But Sheik Sharif’s government seems hobbled by the same tired, intractable clan divisions and lack of skills that torpedoed the 14 previous transitional governments. There have been glimmers of hope, such as the government passing a national budget for the first time in years and using legitimate tax money from Mogadishu’s port to pay its soldiers. But the bigger picture is grim. In the past few weeks, it proved very difficult for the government even to organize its various militias to jointly defend the few blocks it still controls.

The pattern is clear, and may not be broken anytime soon: A weak government means more violence, means weaker government, which means still more violence, and so on.

“With all the fighting that’s going on, this government can’t attract the best Somalis,†said Mohamed Osman Aden, a Somali diplomat in Kenya. “The good Somalis are not going to come when it’s so violent. Would you?â€

Source: NY Times