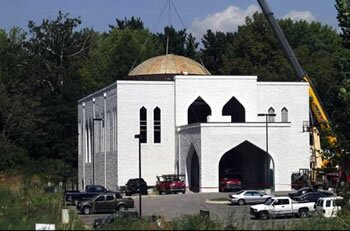

Bartamaha (Nairobi):-Kiarash Jahed looked skyward as workers gingerly pulled tethers to fit a two-ton dome into place. The installation at the Muslim Community Center of Louisville along Westport Road last Wednesday marked the crowning moment so far in the construction of the city’s newest mosque.

Bartamaha (Nairobi):-Kiarash Jahed looked skyward as workers gingerly pulled tethers to fit a two-ton dome into place. The installation at the Muslim Community Center of Louisville along Westport Road last Wednesday marked the crowning moment so far in the construction of the city’s newest mosque.

With the dome and dramatically arched windows, the mosque and an adjacent school under construction represent the boldest architectural expression of Islam to date in Louisville, a city where thousands of Muslims have lived and worshiped for years in mosques located in houses and other small buildings.

“I feel elated,” said Jahed, a medical resident who sometimes leads prayer services at the center. “This is sort of the peak moment of the project.”

Elsewhere, the growing number of mosques has drawn opposition in places ranging from California to smaller cities in Kentucky and Tennessee. The location of a planned Islamic center in Manhattan — near ground zero — has drawn the strongest protests.

But the rise of the Muslim Community Center of Louisville and the expansion of other local mosques have taken place with relatively little fanfare or debate.

“The mosque here is intended as a place of interaction for all faiths, to know firsthand what Muslims believe in and why,” said Dr. Ammar Almasalkhi, a board member of both the center and the adjacent Islamic School of Louisville.

Almasalkhi, who practices pulmonary medicine in Louisville, said mosque supporters are on good terms with their neighbors and have “received so many words of encouragement and letters of support from non-Muslim friends.”

Mosque leaders modified their plans after neighbors sued in 2005, objecting to some of the design elements originally approved by the Louisville Metro Board of Zoning Adjustment. But both sides reached an agreement over a scaled-back plan, and they say the disputes were not over religion.

“It was strictly zoning,” said one of the plaintiffs, neighbor William Booker. “We weren’t trying to stop the mosque. We wanted to try to retain the agricultural appearance of this area as much as possible.”

Some cities fearful

Mosque proposals elsewhere, including one in Florence, Ky., have had to deal with a different kind of opposition, with some saying mosques could breed violent extremism in the name of Islam, such as that promoted by al-Qaida.

Mosque leaders here and elsewhere dispute such claims, saying the mosques will help members integrate into society and teach that Islam prohibits the killing of civilians.

While 62 percent of Americans say Muslims have the same right as anybody else to build houses of worship, 25 percent say communities that don’t want mosques should have the right to prohibit them, according to an August poll by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life.

Last month in Mayfield, Ky., a zoning board voted against a Somali group’s mosque plan, citing parking concerns. An overflow crowd applauded its vote. The American Civil Liberties Union of Kentucky says it is investigating whether anti-religious bias played a role.

Plans for the Florence mosque have drawn opposition fueled by an Internet campaign that questions whether the mosque will have any ties to Muslims who commit terrorism or honor killings.

Construction vehicles at a Tennessee mosque site were vandalized in late August, with one set on fire, and a mosque in California was the recipient of a plastic pig — an animal Muslims consider unclean — with an anti-Islamic message.

Far more controversy has swirled around a proposed Islamic center in New York on a site about two blocks from the World Trade Center, which was destroyed by radical Islamist terrorists in 2001 at the cost of nearly 3,000 lives.

The Pew survey found that 51 percent of Americans oppose that project.

Those who want to build the New York mosque and community center say the aim is to teach Islam as compatible with American values.

Others, however, say it’s insensitive to build it there — and reminiscent of past cases in which large mosques were opened near the scene of Muslim military victories.

Some Louisville-area residents who have spoken out against the mosque said in interviews that they believe the Manhattan proposal is different from those in their own community.

“I just am in opposition (to) putting a mosque at such an inappropriate place,” said S.E. Harlowe, a retired U.S. Army brigadier general from Floyds Knobs, Ind., who wrote a letter to the editor of The Courier-Journal opposing the Manhattan mosque. “Other than that, people can do as they will. … We have freedom of religion here.”

In a looming event already drawing protests in Muslim nations, a Florida church plans an “International Burn a Quran Day” on Saturday’s anniversary of the Sept. 11 attacks.

In support of Islam

Louisville religious groups are planning events in opposition to that. Clifton Universalist Unitarian Church will host a continuous reading of the Quran on Sept. 11 from 9:11 a.m. to 9:11 p.m. The same day, Interfaith Paths to Peace plans displays and readings from the sacred texts of various world religions on such topics as peace and cooperation at 11:30 a.m. at Highland Baptist Church.

“Most people here are peaceful,” Haleh Karimi, a Muslim member of the interfaith group’s board, said after hearing news of anti-Islamic acts in other communities. “I’m so happy to be part of this community.”

Almasalkhi, a native of Syria, said it’s sad to see mosque opposition around the country, but overall he’s proud to live in a country “that provides not just lip service but a true meaning to freedom of religion.”

Almasalkhi added that true Muslims flatly reject terrorism.

“Islam as a faith and teaching has never been responsible for the actions of extremists (and) what they have done on Sept. 11 in New York,” said Almasalkhi, who also chairs the Council of Islamic Organizations of Kentucky.

“Hopefully Muslims won’t feel afraid living in this country,” he added. “Hopefully they will continue to believe that the Constitution still means something.”

Serving a cultural mix

No one has a solid count of Louisville’s Muslims, but the city has at least eight mosques, and at least two of them opened or expanded within the past decade. They serve a mix of American-born and immigrant Muslims, including thousands of refugees from such lands as Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia and the former Soviet Union and Yugoslavia.

Semsudin Haseljic, president of the Bosniak-American Islamic Center on Six Mile Lane, said he isn’t aware of anti-Muslim activism here.

“I haven’t heard anybody else experiencing anything of that sort,” he said.

But Jahed lamented that the mosque controversies elsewhere show “we still don’t have cultural authenticity.”

“We are still seen as the foreigner,” he said. “It’s partly our fault. We haven’t made enough of an effort to really integrate.”

That’s due partially, he said, to the fact that Muslims in the past often consisted of immigrant groups just trying to establish homes and jobs in a new land. But now, he said, they need to contribute more to society at large.

“We can’t sit back,” agreed Dr. Asim Piracha, a Pakistani-American who practices ophthalmology. He cited steps in that direction — such as fundraising by local Muslims to help disaster victims in Haiti and Pakistan. “We’ve got to get involved, being active, productive citizens,” he said.

Reporter Peter Smith can be reached at (502) 582-4469

—————————————

Source:- Louisville Courier-Journal