Somalia’s tentative recovery

FINALLY, some good news from Somalia: according to a new issue of the French weekly Paris Match, the Somali shilling has doubled in value against the dollar over the last two years. The international airport at Mogadishu has been refurbished, and now boasts of a duty-free shop. Turkish Airlines operates three weekly flights to Istanbul as a result of a visit by Recep Erdogan, the Turkish Prime Minister. Tellingly, the immigration form for arriving passengers no longer contains the old entry for firearms being carried in.

FINALLY, some good news from Somalia: according to a new issue of the French weekly Paris Match, the Somali shilling has doubled in value against the dollar over the last two years. The international airport at Mogadishu has been refurbished, and now boasts of a duty-free shop. Turkish Airlines operates three weekly flights to Istanbul as a result of a visit by Recep Erdogan, the Turkish Prime Minister. Tellingly, the immigration form for arriving passengers no longer contains the old entry for firearms being carried in.

The same issue of the magazine informs us that the price of fish has shot up because of new restaurants opening up to cater for the increasing number of foreigners and returning expatriate Somalis. A new six-story hotel is coming up in the capital. Male and female students are returning to schools and university.

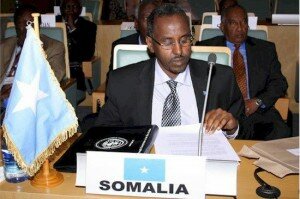

In large measure, this return to normalcy is due to the defeat of the terrorist group Harkat al-Mujahideen al-Shebab by the forces of the African Mission for Somalia established by the Organisation of African Unity (OAU). This force, sanctioned by the UN, has been very successful in pushing the terrorists out of Mogadishu, and from other towns as well. The effort to eject the extremist thugs out of the country began last year, and has made steady success.

The other factor underpinning the Somali success story is the return of some 300,000 migrants who had been forced to leave their country due to the complete breakdown of law and order. With their money and their entrepreneurial spirit, the rebuilding of Somalia is under way. Scattered across North America and Europe, this diaspora made its mark by dint of hard work and self-help.

Considering that Somalia was for years synonymous with our notion of a failed state, this recovery is nothing short of miraculous. For decades, the country was caught up in murderous tribal warfare that destroyed much of Mogadishu. A slice of this mayhem was captured by the Nineties film Blackhawk Down that depicted the failed American effort to restore some order and bring in food supplies. In the event, Bill Clinton pulled out US forces after they lost a number of soldiers. The Pakistani contingent sent as part of a UN peacekeeping force also sustained heavy casualties.

Whatever was left was demolished by the Shebab in their bid to impose a Taliban-like theocracy on Somalia. These holy warriors modelled themselves on the Afghan and Pakistani Taliban, banning everything from music to sports. Symbolising the return to sanity is the reopening of the National Theatre, a building earlier used by the Shebab as an arms depot and then as a public toilet.

I went to Mogadishu in the mid-Sixties for a vacation from university when my father was sent there by Unesco to establish a university and a public education system for the newly independent state. It was a small, sleepy town then with proud but friendly people. I recall being very struck by the fact that when our driver brought my father home from work, he would come and chat with us in the living room for a little while. His brother, my father told us, was the education minister.

Since that trip, I have followed the travails of the country with growing dismay. Repeated bouts of famine, in part caused by the civil war, only hastened Somalia’s descent into chaos. After a provisional government was established with international support, the country was again subjected to yet another round of violence when the Shebab attempted to take control. For years, Mogadishu was a divided city with the young terrorists calling the shots.

The country is also plagued by a nest of pirates who prey on ships sailing hundreds of miles from the coast. Their links to the Shebab have been reported, and their depredations have been the subject of widespread international concern and action. The success of these pirates illustrates what happens when a state loses control, and has some parallels with Pakistan’s tribal areas.

The return of a tenuous stability augurs well for this east African state. If it can build democratic institutions, it might well emerge from decades of violence and abject poverty. Luckily, it has many well-wishers: the West as well as its neighbours realise that a collapsed Somali state means trouble for the entire region.

Being a gambler and an eternal optimist, after I read the Paris Match article, I sent a text message to my son in Karachi, asking him to buy me some Somali shillings in the expectation that they would rise further in value. He must have thought I had lost my mind here in Sri Lanka, and replied: “Hahaha!” No doubt he remembered an earlier punt when I bought five thousand rupees worth of Afghanis just before the Americans attacked Afghanistan some 10 years ago. I calculated that the Afghan economy had no way to go but up, and the Americans would pour in aid to put the country back on its feet. Sure enough, the Afghani proceeded to gain in value. When I thought I’d take my profit, I discovered that there were three different kinds of Afghanis out there, and inevitably, I had the wrong sort…

One lesson from Somalia is that given political will and firm military action, the extremist scourge can be defeated. The reality is that jihadis, whether in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen or Somalia, have very little public support. Even though they fly the Islamic banner, they are actually fighting for power and money. They recruit poor, gullible young men to their cause, but the leaders are cynical killers who use religion as a ploy to silence their opponents.

In Somalia, the Shebab faded away when confronted with well armed and disciplined troops. While they killed and terrorised unarmed civilians, they were no match for the OAU force. In Swat, Mullah Fazlullah’s gang melted away when the Pakistan army finally went in.

So while rejoicing in Somalia’s recovery from Islamist terrorism, let us draw the relevant lessons to apply in Pakistan.

Source:- Dawn

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar