Somalia: Can Kenya’s invasion of Kismayo put an end to al-Shabab for good?

KISMAYO, Somalia — Incredibly, this small port city, a study in ruin in a country that is a parable of ruin,boasts two airports. There is the new airport, as it’s known, laughably to all who touch down there, which lies 10 miles inland and consists of a couple of mostly tarmacked runways and the carcass of a terminal. Kismayo International Airport, in blue block letters, is just barely visible above the building’s sun-bleached cornice. Stencil-painted on the wall below that, and more legible, is the flag of the Islamist insurgent movement that until recently controlled Kismayo, Harakat al-Shabab al-Mujahideen, or al-Shabab — a black rectangle over white classical Somali script that reads “There Is No God But God.”

KISMAYO, Somalia — Incredibly, this small port city, a study in ruin in a country that is a parable of ruin,boasts two airports. There is the new airport, as it’s known, laughably to all who touch down there, which lies 10 miles inland and consists of a couple of mostly tarmacked runways and the carcass of a terminal. Kismayo International Airport, in blue block letters, is just barely visible above the building’s sun-bleached cornice. Stencil-painted on the wall below that, and more legible, is the flag of the Islamist insurgent movement that until recently controlled Kismayo, Harakat al-Shabab al-Mujahideen, or al-Shabab — a black rectangle over white classical Somali script that reads “There Is No God But God.”

A half-hour drive away, hidden among the sand dunes just outside Kismayo, is the long-dormant “old” airport. It offers one dirt runway and, in the place of a terminal, a half-century-old army personnel carrier, rusted to the color of primeval toast, left over from the days when Kismayo was part of Italian Somaliland. What it lacks in infrastructure the old airport makes up for in exclusive coastal access. The beach nearby was once popular with European sunbathers, but after two decades of civil war, it’s so deserted one could walk along the Indian Ocean for days without encountering another person.

Both airports now belong to the Kenya Defense Forces (KDF), which swept into Kismayo in early October with three mechanized battalions, backed up by soldiers from the Somali National Army and a local militia called Ras Kamboni; they are the poles in the southern axis of Sector 2, as the KDF calls its new domain in Somalia, which spans the country’s Lower Juba and Gedo provinces. The southern axis is one of the more cinematic war zones Africa has to offer at the moment; aside from the airports, it includes an encampment overlooking the ocean and the Kismayo port, which on most days calls to mind a Turner painting, with carved-wood barges tethered two deep to its dock.

Operation Linda Nchi is the first combat deployment ever undertaken by the KDF; until now it has been confined to supporting U.N. peacekeeping missions. The original aim of Linda Nchi, which means “Protect the Nation” in Kiswahili, was to keep the al Qaeda-affiliated al-Shabab out of Kenya. But the KDF has now been in Somalia for over a year. It has 2,500 troops here and plans to deploy 2,000 more by next year. According to commanders, the new mission is to “mop up” what is left of al-Shabab — that is, to end the Islamist insurgency for good.

The KDF soldiers have made a convincing show of going to war. At headquarters, at the new airport, they’ve dug hundreds of bunkers into the red earth and undergrowth and have set up tarp-roofed tents and makeshift showers. Artillery guns and tanks sit among them in a manner that suggests imminent battle; but the troops here haven’t seen action in months. Lots of green plastic sandbags are everywhere, as well as trucks and armored personnel carriers with AU, for African Union, printed on their doors. A surveillance drone sits in the hangar.

Nearby is the officers’ lounge, a thatched hut outfitted with thermoses of lemon tea and a television with satellite-dish service. In early December, Col. Adan Hassan, commander of the 3rd Battalion, who oversees the airport, greeted me and three other reporters there. A tall, stoop-shouldered man, Hassan wore well-pressed fatigues and wire-rim glasses. By way of introduction, he told us that the area around us was still alive with al-Shabab holdouts. “They usually start firing in the evening. When they fire, don’t move; just look there,” he said, pointing vaguely toward the desert. He looked at the female reporters. “For the ladies, you can sleep in the armored personnel carriers if you want.”

At the far end of the hut a bedsheet was draped on the wall. A projector sat before it. A soldier at a laptop, his helmet strapped on tightly, a semiautomatic rifle leaning against his chair, brought up a PowerPoint presentation. A series of slides outlined the obstacles facing Kenya in Somalia. Hassan read them off. Commenting on a slide titled “Demography,” he pointed out that, in Somalia, “Loyalty revolves around clan” and “Clan is unifying and divisive factor.” Under “Challenges in Local Areas,” he listed “nonexistent government structures” and “vastness of sector.”

I asked Hassan how many al-Shabab fighters Kenya had killed or captured on its march to Kismayo. “I don’t have the number at my fingertips, but I assure you we degraded them,” he said. “When we entered this town, it was deserted. Many people had fled. But now, you wouldn’t believe it. They are welcoming us. It’s because of the confidence we’ve given them, the security we’ve given them.”

All the officers in the hut, I noticed, including Hassan, wore new white-and-green AU armbands with gold trim. They were clearly fresh out of the box, meant to emphasize to us that the Kenyan troops are part of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM). I asked Hassan how Kenya’s and AMISOM’s objectives coincide, or don’t. They are one and the same, he assured me. “We’re not an occupational force,” he said. “If the Somali people are secure, we’re secure.”

Kenya’s particular security interests kept creeping back into his answers, however. When another reporter asked how a spate of recent bombings in Kenya, believed to be al-Shabab-related, influenced the operation, Hassan made clear that “what is happening in Kenya has nothing to do with what we’re doing here.” But then, he added, “We’ll finish them here in Somalia; then we’ll look for them in Kenya.” Asked about Kismayo, he said it “was not an objective of the KDF. It was an AMISOM objective.”

This both is and isn’t true. Since AMISOM decided to assemble a multinational force to go after al-Shabab in 2010, taking Kismayo has been viewed as the endgame, at least of the military phase of the mission. The city was al-Shabab’s base and the port its economic engine, providing an estimated $35 million to $50 million a year to the group. And as the interests of the United States and European Union, Somalia’s largest bilateral and multilateral donors, respectively, have shifted in the last few years from targeting high-value al Qaeda in East Africa figures to degrading al-Shabab and shoring up Somalia, Kismayo began to be viewed as a priority by them too. In the West, the capture of the city is now seen not just as a win against Islamist political extremism, but a symbolic victory in the battle for what may be the world’s most dysfunctional country. The United Nations covers AMISOM’s budget, and most of that outlay is covered by Europe. Washington has put at least $500 million into AMISOM and the Somali army since 2007. The Pentagon and CIA, which have hugely increased operations in Somalia since the 9/11 attacks, provide intelligence support to AMISOM, along with the British, French, and Israelis. Despite all this help, Kenya’s victory in Kismayo was greeted with surprised joy. No one expected the KDF to prevail so quickly.

But it is also the case that Kenya was never interested in pitching into the bloody battle for the capital, Mogadishu, which has killed over 500 AMISOM troops. Kenya has always wanted to get in and out of Somalia as quickly as possible, and it has known all along that taking Kismayo, just 180 miles from the Kenya-Somalia border and the nearest city, with a massive show of force could be the way to do that. Capturing Kismayo was “significant for Kenya because there were serious questions about its willingness to fight,” a Western diplomat told me.

More of a mystery is why Kenyan President Mwai Kibaki chose to launch Linda Nchi to begin with. The question is still a matter of gossip among Kenya’s political class over a year after the operation began. Theories abound. There are the strange politics of the African Union, which has few of the dictates for cooperation that bind EU countries and at least as much fractiousness. Some think AU members, particularly Ethiopia, browbeat Kibaki into providing troops. Some think he has been watching with growing anxiety the rise of Rwanda and Uganda (the latter has contributed and lost the most troops in Somalia), whose soldiers-turned-presidents have turned their small countries into economic performers and darlings of the West, while the poverty and corruption in Kenya, once East Africa’s leader, have worsened. Still others think Kibaki was so humiliated by the election violence that overtook Kenya in 2007 — official estimates are that 1,400 people were killed — and by the International Criminal Court indictments that followed, that he jumped at the chance to edit his legacy with a patriotic war against Islamists in the run-up to an election year. (The Kenyan elections have since been postponed to 2013.) Some believe it all. “Kenya’s very vulnerable right now,” a U.N. employee who works on Somali issues told me. When I asked in what way, this person said, “In every way.”

Then there are the usual noises about murky monetary interests. Kenyan businessmen want to wrap up the black market that flows through Kismayo, it is said, or energy companies want Kenya to control disputed coastal waters so they can tap unproven hydrocarbon reserves offshore. One certainty is that Kenya is trying to attract investment to a new port on the island of Lamu; the more trade it can siphon off from Kismayo, the better for Kenya.

But “Protect the Nation” can be taken at face value too. The mess of security and humanitarian problems caused by Somalia has become a national obsession in Kenya. A half-century ago, the tribal domains that span the two countries were ineptly split, resulting in a long-running border dispute. Today, roughly 2.5 million Somalis live in Kenya, many in dire poverty. Half a million of them inhabit camps around the town of Dadaab, just across the border with Somalia, in what may be the world’s largest permanent refugee crisis. Since al-Shabab came to power in southern Somalia in 2009, it has taken advantage of a 400-mile-long porous border to sow a campaign of terror in Kenya. According to a report by the U.N. Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea, al-Shabab recruits disaffected youth from refugee camps and Somali slums in Nairobi, Mombasa, and other cities (along with Muslim and Christian Kenyans) to carry out bombings and shootings in Kenya. Churches, police stations, and city buses have been targeted. The last month has seen a series of grenade attacks in Nairobi’s Somali-dominated Eastleigh neighborhood, including one on the night of Dec. 7, at a mosque, that killed five people and maimed a member of parliament.

Kenya had a real and pressing need to pursue al-Shabab, in other words, and particularly to target Kismayo. And walking around the KDF camp at the airport, talking to soldiers, I found they all repeated the same mantra: We’re defending our home. Contrary to what Hassan had said, the attacks in Kenya had everything to do with the mission, as they saw it. (The similarities to the arguments one heard in the run-up to the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq — “we’ll fight them there so we don’t have to fight them here” — were striking.)

Personal pride was involved too. I spoke with soldiers who’d been in the KDF for 20 and 30 years. They had watched their army progress from a barely trained, ill-provisioned afterthought to one of the most professional fighting forces on the continent. They wanted the world to know about it. “We’re ready to fight a real war now,” one longtime enlisted man told me.

Even with that advantage, though, President Kibaki could hardly have arrived at the decision to invade Somalia more awkwardly. Certain members of his government had encouraged him to respond to al-Shabab by annexing part of Somalia’s southern borderland, in an effort to create a kind of Kenyan protectorate that would be known as Jubaland. The United States and the European Union, however, discouraged the plan. Still, beginning in 2008, Kenya trained and equipped the Ras Kamboni militia, which is believed to have several hundred men around Kismayo. In a scenario that invited visions of the Bay of Pigs invasion, the KDF drew up plans to assemble an army made up of Ras Kamboni militiamen and (taking a cue from its enemy, apparently) Somalis from refugee camps to launch a proxy war against al-Shabab. Kenya’s Western allies refused to sign off on that scheme. “We saw it as very risky and potentially illegal,” one Western diplomat told me.

Kenya had good reasons for staying out of Somalia, and one very good reason in particular — Ethiopia. In 2006, Ethiopian troops invaded, with U.S. military support, after years of cross-border incursions by Somali militias. They fought their way impressively to Mogadishu, where they joined up with Somali national troops in an attempt to pacify the city. It was a disaster. Thousands of civilians were killed; several hundred thousand were displaced. Attacks on Ethiopian troops increased, as did attacks in Ethiopia. Troop morale plummeted, and by 2009, al-Shabab had the Ethiopians on their heels. Somalia was turning into another graveyard for empires, it appeared to Kibaki. If Ethiopia, with its soldiers hardened by years of civil war and with its American helicopters, could find itself in such a quagmire, he worried, what fate awaited Kenya?

Then something unexpected happened: Somalia began to turn around. The populace began turning on al-Shabab. The African Union stood up its army, and slowly but steadily it cleared the Islamists from Mogadishu. The Ethiopians regained their composure and took control in the fractious southwest border region. Thanks to international maritime patrols, piracy off the coast abated. And the United States and European Union poured funds into the effort. For the first time in 20 years, people started talking about Somalia showing promise. After decades of default cynicism toward Somalia, “There’s now a fresh look being taken,” the U.S. special representative for Somalia, James Swan, told me.

By the fall of 2011, the African Union had 12,000 troops in Somalia, most in Mogadishu, and Kibaki faced a choice: Either he could play it safe and disappoint his regional partners and the growing chorus of Kenyans calling for a war with al-Shabab, or he could get involved and risk a campaign of reactionary attacks in Kenya, along with television news scenes of Kenyan soldiers dying in the Somali desert — all of it in the run-up to an election. After a spate of al-Shabab-sponsored kidnappings of European tourists and aid workers in Kenya, the choice was all but made for him.

Kibaki announced the invasion in October 2011 — two days after it had started. Kenya’s neighbors were taken aback; few of them had been consulted, it seems. No one was as surprised as the Transitional Federal Government in Mogadishu, which publicly questioned Linda Nchi. Only after a round of frenzied post-facto shuttle diplomacy with Nairobi did it voice approval. Even the African Union had its doubts. The KDF force wasn’t formally admitted to AMISOM until four months later, in February of this year.

Linda Nchi’s opening went as badly as its planning. For reasons that escape comprehension, the KDF moved in as the fall rainy season began. Vehicles got bogged down in rain and mud. When Kenyan Prime Minister Raila Odinga traveled to Israel to ask for help, al-Shabab had a public relations field day. Not only was Kenya a stooge of the West; it was now engaged in a war against Islam. Before a shot had been fired, the Somali populace was turning on Kenya.

But, after a series of false starts, the Kenyan forces found their rhythm. Thanks to a special agreement with AMISOM, they were allowed to bring in bombers and warships. They pounded al-Shabab positions across Lower Juba, Middle Juba, and Gedo, and then moved north, taking town after town. After a stiff 10-day fight at the village of Miido, the KDF turned east and raced for the coast. In the early-morning hours of Sept. 28, special-operations forces units landed on the beach and parachuted into the interior. They were followed later that day by two mechanized columns, including Ras Kamboni and the Somali National Army, which converged on Kismayo from the west and south, while an amphibious detachment landed on the beach. They quickly overtook a contingent of al-Shabab fighters holed up in caves in a lime quarry on Kismayo’s northern outskirts.

The assault on the city was well choreographed — and, as it turned out, overkill. A field commander told me, “The opposition was not what we expected.” When I asked why that was, a faint smile overtook his lips, and he said, “Maybe they knew they were up against a better force.” The truth, however, is more complicated. Al-Shabab had no intention of defending Kismayo.

Mogadishu is famous for its destroyed infrastructure. By contrast, Kismayo, home to about 180,000 people, is striking for its lack of infrastructure. Locals will tell you this is because Kismayo, a medieval fishing settlement that evolved into a spur of the Swahili-coast livestock trade during the colonial era, has changed hands so often. In the 1890s, the sultan of Muscat ceded Kismayo to Britain, which in turn gave it to Italy. After Somalia won its independence in 1960, Kismayo’s business elite turned its port into a regional trade hub, but when the civil war began in 1991, the city was flung between warlords. U.S. Marines occupied it, with little effect. It was fought over for more than a decade by local militias, the Transitional Federal Government, the Ethiopians, Ras Kamboni, and al-Shabab’s predecessor, the Islamic Courts Union, which shifted its base from Mogadishu to Kismayo in 2006. Al-Shabab, the extremist wing of the Islamic Courts Union, took full control of the city in late 2009.

The day after arriving at the airport camp, we piled into an armored personnel carrier in a military convoy. At the front of the line of vehicles was a SUV containing a machine that jams radio frequencies used to detonate improvised explosive devices. The KDF soldiers wore body armor and helmets. Riding heedlessly alongside us in a “technical” — the battlewagon of choice in Somalia, a stripped-down pickup truck mounted with a Russian-made DShK anti-aircraft gun — was their Ras Kamboni escort. The only thing the gunner had on for protection was a pair of earphones.

We passed by an open-air dump where garbage smoldered, by encampments of domed huts made from tree branches and cloth, and then into Kismayo’s dirt streets, which are lined with one-story stucco buildings. Al-Shabab insignias were still prominent on walls, a reminder of the suffering inflicted. When al-Shabab came into southern Somalia, it helped decimate what had been the country’s breadbasket by taxing and harassing farmers and pastoralists, and it then forced out aid agencies that were trying to feed the population. Kismayo’s nameless main road, the only paved one, runs through Liberty Square, where a toppled monumental column erected after independence now lies on the ground in blocks. Under al-Shabab, Liberty Square became a stage for public floggings, dismemberments, and executions. When its police wanted to bury people up to their necks and then stone them to death, as they did to a young woman accused of adultery in 2008, they used the softer ground of the nearby soccer stadium.

At the Kismayo port, freighters from India, Pakistan, and Syria were docked, unloading shipments of fruit juice, chewing gum, milk, and sugar. Al-Shabab derived most of its revenue from taxing the goods that went in and out of it. No great fans of al-Shabab, the merchants nonetheless allowed it to rule Kismayo because it was good for business — al-Shabab simplified the bribery system and did away with competing militia roadblocks set up to extort trade. Now the KDF occupies the port’s warehouses and inspects every ship.

A delegation of merchants and community leaders met us in one of the warehouses. One by one, they came before us to list their grievances. “We ask for things from the central government, but they don’t give us anything,” one man complained. “The world is doing nothing for us.”

A port administrator I met, Abduli, said that though al-Shabab was good for business in certain ways, it wasn’t worth the toll the group exacted on Kismayo. “In the port, in the market, Shabab always, ‘Give money, give money, give money.’ Shabab tax hundred dollars per shipment!” he said. “Shabab kill everyone. Kill mothers, kill babies, kill everything.” When I asked whether he was affiliated with a particular militia or other group, Abduli admitted he was a member of Ras Kamboni. But, he said, “Now clan is over. Tribe, over.”

“What comes next?” I asked.

“Is come tourism!” he said. “Is come tourism to Kismayo. Kismayo beautiful. Every culture, black and white, come. I want life, you know? I want the government. I want the administration. Shabab attacking is problem only.”

Al-Shabab is still attacking. The week before we arrived, gunmen shot up the home of a local security official. Three days later, grenades were thrown into a crowd. The victims were brought to Kismayo General Hospital. They lay in beds in the hospital’s courtyard, under a tree, surrounded by refuse. I spoke with a woman whose head and leg were bandaged. A grenade hit her near the temple, she told me, and then landed in the lap of a man sitting near her. It killed him, but she somehow survived. “I was very lucky,” she said. An even worse wound was caused by a bullet to her leg, which didn’t come from the attackers. After the grenades were thrown, Ras Kamboni troops present at the scene shot indiscriminately into the crowd and the air. Two other casualties I met at the hospital were uninjured by the explosions but were shot afterward by the militiamen.

After returning from the hospital, I walked out to the wire at the new airport camp. A line of small bunkers with machine gun nests faced an expanse of sand and shrubs. I spoke to a pair of Kenyan soldiers who were playing checkers with soda bottle caps. I asked what they thought of their counterparts in Ras Kamboni and the Somali National Army. Their feelings were mixed, they said. All the Somalis were ill-equipped, badly trained, and badly paid (if paid at all), but some were more disciplined than others and some knew how to fight al-Shabab.

“In guerrilla warfare you don’t need training,” one of the soldiers told me. “You just need to know how to shoot and duck.”

I asked whether he trusted the Somalis. “We have no choice,” he said. It’s well-known to the troops here that Ras Kamboni’s leader, Sheikh Ahmed Madobe, was a high-ranking administrator in al-Shabab before turning against them. Indeed, Ras Kamboni was an Islamist insurgency before al-Shabab was even created. Many families in the area have members in al-Shabab and others in Ras Kamboni or the Somali army. The Kenyans suspect they tip one another off about operations. But there’s little he can do about it, the Kenyan soldier said. “Now we are brothers.”

Some Ras Kamboni fighters have been tasked with guarding the villages around Kismayo, where they live among the population. Others man the airport terminal. They stand out starkly from the KDF troops. They wear tattered solid-green fatigues and have no body armor, helmets, or, often, boots — they’ve grown used to facing al-Shabab head-on in sandals, with old single-shot rifles. In the terminal, whose halls smell of urine and excrement, they sleep on blankets on the floor beside walls decorated with graffiti left by al-Shabab. One picture shows an al-Shabab technical shooting at a helicopter. It looks like a child’s rendering of a scene from Black Hawk Down, and indeed it may be. Al-Shabab reportedly recruited children from Kismayo to put on the front line. (And the 1993 episode has become part of the national mythos.)

Ras Kamboni and the Somali national troops have been accused of mistreating Somalis. So has the KDF. So far, Kenya has refused to allow human rights investigators into the places under its control; nonetheless,Human Rights Watch has advised Somali refugees in Kenya who fled the fighting to not return yet, because they may face abuse by the KDF.

This is precisely what President Kibaki wanted to avoid. Perhaps for that reason, after taking Kismayo, Kenya has cooled its heels. Hassan spends most of his time these days sitting in a hut near his tent sipping tea and speaking on a cell phone. The KDF soldiers appear to be mostly concerned with keeping a neat camp. One day, I watched a group of them sweep a runway — for two hours. I asked how they liked life during wartime. “I’ve been here for six months,” one soldier said. “Can you find me an American wife?”

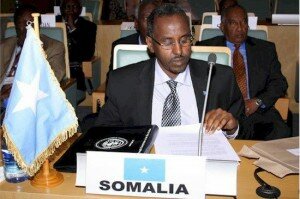

It’s generally assumed that success in Somalia, particularly in the south, depends on the ability of the African Union and the new Somali president, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, to help the country’s desperate population as quickly as possible. They’re already behind. Despite a budget that will approach $800 million this year, AMISOM has only just begun to think about planning for the peace — in part because it thought the fighting would drag on much longer. “They never expected to win this fast. They thought they’d have time to figure out the civilian component,” says Alex Rondos, the EU special representative to the Horn of Africa. “They’re victims of their own success.”

When Linda Nchi began last year, an editorial in the Daily Nation, Kenya’s leading newspaper, pointed out that after troops captured territory, “Kenya’s biggest challenge is to prosecute an effective counter-insurgency campaign to degrade Al-Shabaab.” Everyone I spoke with, from AMISOM officials to diplomats, agreed with that analysis. They also agreed that al-Shabab is probably not in retreat from southern Somalia so much as it’s in retrenchment. With contributions from the Somali diaspora drying up thanks to its growing unpopularity, al-Shabab knew, long before the KDF reached Kismayo, that it didn’t have the manpower or money to face a conventional army. So its fighters have blended into the population, where they are recruiting young freelance assassins and waiting to see what AMISOM does next. Al-Shabab fighters have studied the Taliban and Iraqi insurgencies, and in some cases contributed to them. “Shabab has been preparing for this onslaught for a long time. They’ve been preparing to sink in, to make the leadership mobile,” an intelligence analyst involved in operations against al-Shabab told me. “Time is not on our side.”

Yet neither AMISOM nor the KDF appears to have a long-term counterinsurgency strategy. One possible reason for this is that senior officials in the new Somali administration and AMISOM are involved in negotiations with al-Shabab to disarm. Another, more obvious, reason is that Kenya has no experience in counterinsurgency (its Anti-Terrorism Police Unit investigates al-Shabab affiliates in Kenya). But probably the most important reason is that Kenya doesn’t want to get embroiled in a guerrilla war like the one in Mogadishu. “We’re seeing a caution about going beyond areas they can control,” one diplomat said.

At the same time, Kenya is attempting to demonstrate, with a pitiable lack of subtlety, its allegiance to Ras Kamboni and other powerful elements in the south that are suspicious of Mogadishu and President Mohamud’s centralizing tendencies. Last week, Mohamud and a Somali delegation were supposed to have met with Kenyan officials in Nairobi. The day of their flight, Kenya informed them they’d be denied entrance.

At the airport camp, Hassan said that his mission now is to “mop up” al-Shabab holdouts. But when I asked whether he had men collecting intelligence among the population, he said that was being left to Ras Kamboni. I asked on two occasions whether he was conducting regular patrols. The first time he said no. The second time he said yes, but admitted that they were mostly meant to secure the airport. Asked whether he was conducting systematic house raids or attempting any other standard counterinsurgency measures, Hassan offered: “We’ve cordoned villages.” I asked how many. “Two,” he said.

When I asked why, in the two months since the KDF took Kismayo, no local al-Shabab higher-ups had been captured, even though they are all personally known to Sheikh Madobe and others in the area, he said, “I don’t know. That’s a question for the international community.” He added, “I’m only doing what I’ve been told to do.”

——————————————————————————————————-

James Verini is a Nairobi-based contributor to Foreign Policy.

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar