For Somalia, “Team Canada” means more money, fewer jobs

As the diaspora return in record numbers, tension is growing. Sending money from abroad is one thing, coming back to Somalia is another.

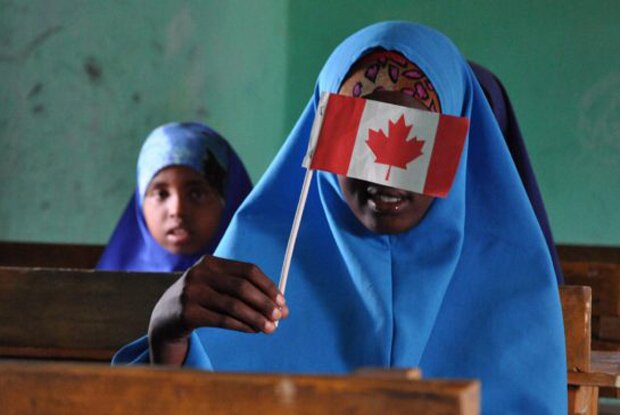

A young student hides her face with a Canadian flag at the Daynille school on the outskirts of Mogadishu. The school, which opened in 2013, was built thanks to remittances and fundraising in Canada.

MOGADISHU, SOMALIA—The tables start to fill inside the air-conditioned Maka al Mukarama Hotel cafe just before sunset. Hunks of black forest cake and frothy cappuccinos are ordered, as members of Mogadishu’s who’s who exchange nods and handshakes. They keep determinedly coming here even though the hotel has been hit twice by suicide bombers from Al Shabab.

Mohamed Ali Nur, arguably Somalia’s most important ambassador, sits at one table in the corner, soon joined by his compatriots. Canadian compatriots, that is.

There’s Abdurahman Hosh Jibril, a longtime Toronto community leader and lawyer who moved back to Somalia to become a member of parliament and political rainmaker. Hassan Abukar, a youth activist who once held a spot on Toronto City Hall’s Youth Committee, has come to his parent’s homeland, as has 20-year-old Ali Liban, who sits behind the hotel front desk in his Blue Jays cap.

The Canadians are everywhere.

When the government here collapsed 23 years ago, hundreds of thousands of Somalis left to seek refuge abroad. Many settled in Canada and much of the money they earned went back to relatives, providing a lifeline for at least 40 per cent of the country.

A 2013 study by Adeso, Oxfam and the Inter-American Dialogue found that Somalia receives approximately $1.3 billion each year in remittances — as money sent back home is known — which is more than foreign aid and investment combined. While the study does not break down remittances by country, Canada is considered a major contributor.

But the future of remittances in Somalia is uncertain.

As the country, and in particular the capital Mogadishu, begins to recover after two decades of war, those from the diaspora are returning in record numbers.

Where there used to be only a couple flights to Mogadishu a week, now there are sometimes five a day. There are so many returning that the government has created the Office of Diaspora Affairs.

That’s generally a good news story. Many bring with them much-needed expertise, education and international backing. But there is tension. Sending money is one thing; coming back to take jobs or reclaim property is another.

Police believe some recent assassinations have not been the actions of the Shabab, as many have claimed, but of those competing for business and political postings. There is much money to be made in Somalia and a deadly jockeying for power.

There is a deadly jockeying for power in resurgent Mogadishu, with Canadians holding many of the country’s most powerful positions. Here, a Somali soldier patrols at the Karan market after a bomb exploded on June 30.

Add to this another dynamic: hawalas. Somalia lacks a banking system, so remittances are delivered mainly through informal money services bureaus (MSBs), known as hawalas. Since the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks and the recent rise of the Shabab, MSBs have been under scrutiny as western governments target terrorist financing.

It has become increasingly hard for MSBs operating in Somalia to maintain accounts with major banks. Financial institutes are deciding that the risk of supporting MSBs is greater than the return.

But if the banks cut off the MSBs — as U.K.-based Barclays and the Merchants Bank in California have threatened — it could quite literally starve Somalia.

The returning diaspora, MSBs and remittances are intricately linked — and there’s a heavy Canadian component.

Canadians have been among the most successful here, populating almost every sector with positions in the government, business and humanitarian communities.

Somalia’s prime minister, Abdiweli Sheikh Ahmed, is Canadian, as is Mogadishu’s former police commissioner, General Abdihakim Dahir Saeed.

Nur, a Toronto native, is Somalia’s ambassador to neighbouring Kenya — the most diplomatically important country for Somalia. Relations with longtime rival Ethiopia are also vital; Canadian Ahmed Abdisalam Adan holds that ambassadorial post.

Nasra Agil, the owner of Mogadishu’s pristine new dollar store that opened near the city’s K4 thoroughfare, is an engineer from Toronto. The director of the women’s rights centre, founder of a primary school, deputy director of Mogadishu’s first think-tank, owners of one of the most popular restaurants, managing director of a major airline: Canadian, Canadian, Canadian, Canadian, Canadian.

Here’s a journalist’s secret: When visiting Mogadishu, my suitcase is heavier on arrival than departure, half of it filled with Tim Hortons coffee. It feels strange bringing coffee from Canada to East Africa, where some of the world’s finest beans are grown, but Timmy’s is a much-needed sip of Canada for the patriotic.

My deliveries here have been likened to dealing crack. Speaking of which: “How is our mayor?” Jibril, known more commonly as Hosh, asks at the Maka al Mukarama on that recent evening. Everyone leans in. No one wants to talk about the Shabab, or Somali politics, or the role of the diaspora, not until hearing the latest on Rob Ford.

This is the strange global village where we live, when sometimes it feels more like Canada in a Mogadishu hotel, and more like Somalia in a Rexdale coffee shop, where citizenship and patriotism can be complicated and where money is sent around the world with just a name and a promise to pay.

Stories about Canadians returning to Somalia are usually dire.

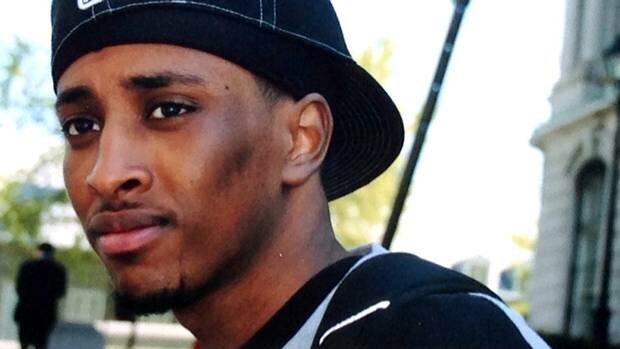

A University of Toronto graduate was convicted in Brampton earlier this year for the crime of attempting to join the Shabab, and counselling another to do the same.Mohamed Hersi was arrested at Toronto’s Pearson airport in 2011, as he was about to board a flight to Cairo. A jury found him guilty of planning to go from Cairo to Somalia — a claim he denied.

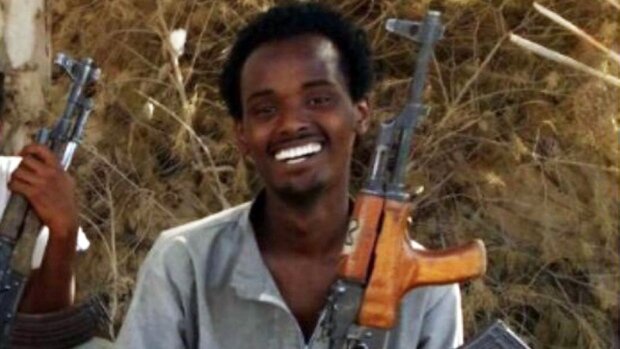

There have been examples of Canadians fighting with the Shabab, such as Mahad Dhore, who left his Markham home in 2009 and led a suicide bombing mission inside Mogadishu’s court complex last year, injuring dozens and killing 30.

Foreign policy regarding Somalia has been driven mainly by these terrorism concerns — the link between western fighters and finances fuelling the Shabab — which is unlikely to change as Al Shabab increasingly strikes outside Somalia’s borders, as it did last September with an assault on Nairobi’s Westgate Mall.

But restrictions that ultimately force MSBs out of business may have short-term counterterrorism benefits, but long-term consequences that would exacerbate conditions such as poverty that terrorist groups can exploit, argues Degan Ali, Adeso’s executive director.

“Somalia doesn’t have an alternative banking system. The MSBs act as the banks. If you don’t have MSBs, the whole economy will collapse,” she says, noting that businesses would have no way to transfer funds and that MSBs are the country’s third-largest earner of GDP.

MSBs operate much like Western Union, although usually charge less than five per cent commission and tend to be more efficient. Money sent from one of the MSBs in Toronto can reach a small Somali village in minutes. The local agent there will be notified and send a text message to the recipient. If the recipient doesn’t have identification, someone can vouch for their identity, although there’s a good chance the agent would know the person.

These funds have been life-saving in some of the most impoverished regions. “This is a country that’s just coming out of a famine,” says Ali. “The last two famines in modern history have happened in Somalia, so this is a place where we’re talking about 50,000 children at death’s door at the risk of dying. Almost three million people are food insecure.”

“If you now take away this lifeline, the source of income and survival for 40 per cent of the population, you’re going to have nearly all of Somalia food insecure, so that’s beyond the famine. That’s beyond a catastrophe.”

Drive outside Mogadishu city limits to Daynille, where the newly paved roads turn to sand, and out of nowhere a school comes into view. This area was once under control of the Shabab; there are still occasional attacks.

Children used to walk kilometres to reach a school in Mogadishu, if they could afford an education at all. But Daynille primary school, which opened last August, provides free education for its students, the majority of whom are orphans or from low-income families.

It is the latest project by Ishardo (International Society Horn of Africa Relief and Development Operations), started by three Somalia-born Canadians in 1998. The organization has also funded a hospital in the area, which provided critical care during the 2011 famine.

“We really see education now as the way to help the community,” said Toronto resident and Ishardo co-founder Mohamed Gilao, who has been fundraising in Canada for the projects for more than a decade.

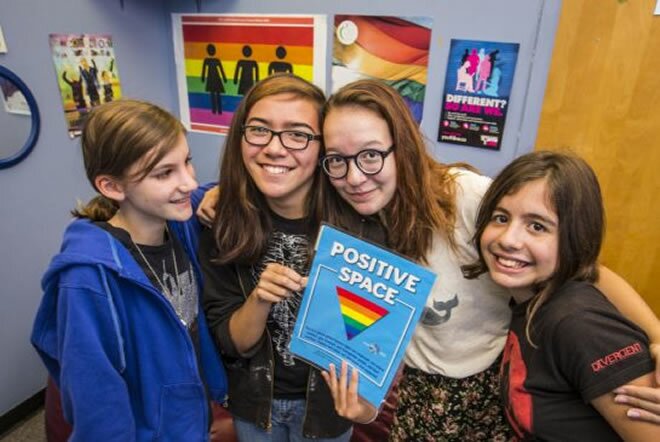

On the day we arrive, the students of Daynille primary school have heard a Canadian reporter is coming, so as soon as the principal ushers us into the first of five classrooms the children begin clapping and waving paper Canadian flags.

Gilao co-ordinates his work with local volunteers and members of his extended family who stayed in Somalia during the 20 years of war and who run the Canadian-funded projects. He travels back and forth to Somalia so he knows the tension that exists with the returning diaspora — and how the Shabab and other militant groups exploit this division.

“Sometimes the people of Somalia are held hostage by terrorist groups and their propaganda. They say the people from outside have lost their nationality, or their religion, or they’ll say they’re spies. This is the challenge.”

“We’re just hoping to peace-build through education.”

A study released last month by the Mogadishu think-tank Heritage Institute notes that “the relationship between returnees and locals in Somalia is complex.”

Security measures often keep the diaspora segregated since they are seen as influential, and therefore targeted by the Shabab. Also, as the report points out, “returnees often find it easier — and more advantageous from a professional networking point of view — to socialize disproportionately with other diaspora returnees.”

Of course the returning diaspora are not a cohesive group. “Generally, non-diaspora Somali communities grasp the diversity among the diaspora returnees,” writes report author Maimuna Mohamud. “They distinguish, for example, between the ‘good diaspora’ who have been successful in their host countries, and the ‘bad’ ones who failed to take advantage of the opportunities available to them.”

Al-Jazeera journalist Hamza Mohamed poked fun at the stereotypes of the returning diaspora by their country of citizenship, dubbing those from Canada who are not part of Mogadishu’s who’s who as “Team Canada YOLO (you only live once).”

“They are everyone’s friends. This group treats life as a party and Somalia as a dance floor,” Mohamed wrote in a column that went viral. “They usually arrive with few things — like a minor criminal record and a Mongolian scripture tattoo they got while under the influence on a night out in Toronto. It’s hard to find them talking about serious issues. Don’t mention school — they have usually dropped out of school and are sensitive discussing this subject. If you want them to unfriend you on Facebook, tag them in photos from your graduation ceremony.”

Back at the Maka al Mukarama Hotel, the Canadians laugh at the column, which also states the British like to put many titles on their business cards and the Americans, well, the Americans are loud.

As the sun sets, the group disperses. It is safer in Mogadishu than it has been in years, but the powerful are targets and travel carefully at night.

There are parting jokes about Ford and the upcoming fall election.

Source: Toronto Star

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar