Yo, ho, ho and a million-dollar McMansion in Kenya

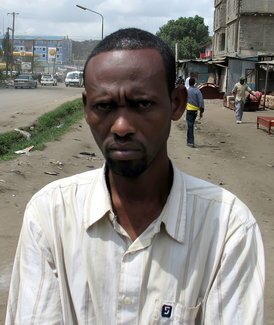

Ali Abdinur Samo, 26, a retired Somali pirate, now lives in Eastleigh, a ramshackle enclave in Nairobi, Kenya.

NAIROBI, Kenya — Young, newly rich and restless, Ali Abdinur Samo wasn’t long for his dead-end homeland of Somalia. The 26-year-old recently decamped to Kenya, East Africa’s land of opportunity, to put his wealth to work.

“I’m looking around,” said Samo, whose close-cropped hair is already flecked with gray, an occupational hazard in his line of work. “I know people who are buying shops, hotels, properties. The economy is strong here, not like back home.”

Samo, if you hadn’t guessed, is a Somali pirate.

“Was a pirate,” he corrected. After earning about $116,000 in two heists, Samo bowed to his worried parents’ pleas and took early retirement in Nairobi, the Kenyan capital, where the fast-growing yet shady economy has quickly become a favorite haven for pirates to spend their ransoms.

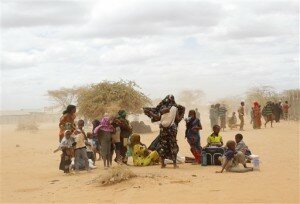

The pirates often describe themselves as saviors with AK-47s, an ad hoc coast guard that’s retaliating against foreign countries for fishing illegally off Somalia’s coast while civil war consumes the government. Follow the trail of their multimillion-dollar booty into neighboring Kenya, however, and you grasp the pirates’ capitalist ambitions.

Rather than investing in their wrecked homeland, pirates are laundering huge sums through property, hotels, shopping arcades and trucking companies in Kenya, according to family members, real estate brokers, money traders and pirates themselves.

They say that ransom money is being funneled to pirate custodians — often well-connected Somali businessmen or religious leaders — through the extensive and largely unregulated Islamic cash-transfer network known as hawala.

“Pirate money is definitely being reinvested in Kenya,” said Stig Jarle Hansen, a Somalia expert at the Norwegian Institute for Urban and Regional Research. “There’s a boom among Somali businessmen in Kenya, and it’s easy to hide the money because there’s so much coming in. And I don’t think Kenyan authorities control or monitor this.”

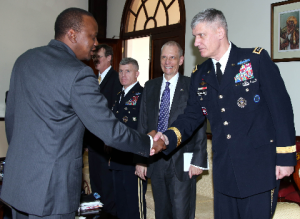

Numerous interviews indicate that Kenya, which Johnnie Carson, the ranking U.S. diplomat for Africa, recently called East Africa’s “keystone state, economically, commercially and financially,” is awash in ransom money.

Experts think that the pirates, who’ve hijacked some three dozen ships in the Indian Ocean this year, have pocketed tens of millions of dollars.

There’s almost nothing worth buying in Somalia, however. Kenya, with its large Somali population and lax authorities — who often are more enthusiastic about taking part in illicit dealings than they are about stamping them out — is a better place to blow through cash.

The sums involved are impossible to pinpoint because little of the money will ever be deposited in savings accounts or recorded by a bank.

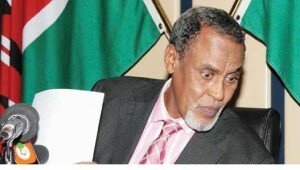

“To avoid the money trail, the ransoms are laundered in goods,” said Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah, the top United Nations diplomat for Somalia, who’s based in Nairobi. “In Kenya, it’s very easy for pirates. They can pay in cash everywhere.”

Ahmed Nur Daud, a 43-year-old Somali refugee in Kenya, bitterly described how his pirate cousin, Suleiman, sent tens of thousands of dollars to a Nairobi businessman who imports big-rig trucks from Abu Dhabi.

“When I saw him the last time he couldn’t buy lunch,” Daud sneered. “Why doesn’t he build his country before investing in another country?”

The answer, it seems, is that many pirates are after hefty returns, not philanthropy. After all, for a young Somali man with guts and little else, setting off to sea with an automatic weapon is the ultimate act of self-interest, a chance to build a house, pay for a wedding and make a down payment on a decent future.

Samo, the retired pirate, put it more simply: “If you have money in Somalia, everyone likes you. No matter what you look like or where you got it from. The more money, the better.”

For a shrouded but unmistakable glimpse inside the pirate money network, visit Eastleigh, a dilapidated, Somali-dominated section of Nairobi dubbed “Little Mogadishu.”

The starting point is often a one-room, Somali-owned hawala bureau such as the one where 34-year-old Abdirahman works, in a crowded shopping arcade on a noisy dirt road that turns to muck in the rain.

Abdirahman, a round-faced clerk in a yellow dress shirt and fraying khakis, met a McClatchy reporter after work and asked that his full name be withheld for his safety. He estimated that over the past several months his office has transferred more than $10 million from Puntland, the lawless northeastern Somali region where most pirate groups are based.

One day in February, one person received $500,000.

The cash came from four different names in Garowe, the Puntland regional capital, and Bossasso, a wild port city. The recipient was a simply dressed man with a Muslim cleric’s long beard.

He stuffed the bricks of cash into his socks, belt and waistband and disappeared.

Where such sums go is difficult to know, but at the nearby al Habib shopping center, 28-year-old shopkeeper Hassan Said Abdullah said that more than a dozen local traders had been evicted recently when a Somali businessman bought up their stalls.

“Someone came to the owner of the building with a lot of cash, and suddenly the rent for those stalls went from $300 or $400 to $1,500,” Abdullah said. “We’ll all be flushed out, those of us with little money. This kind of big money brings problems.”

Clothing and textile shops, often supplied from Dubai, are popular money-laundering avenues for pirates, Somalis say, as are trucking companies that transport goods across East Africa.

Some pirates are paying top dollar for a piece of Nairobi’s booming real-estate action. Osman Guyo, a veteran real-estate agent, recently took a Somali man to see an empty lot in Westlands, an upscale Nairobi suburb that expatriates favor. The seller wanted about $125,000, but was waiting on an assessor’s estimate.

No matter, Guyo’s client said. He offered $1 million on the spot and signed the papers a few days later.

Guyo once overheard the client — who’d been referred by a friend in Eastleigh — talking on his cell phone about the MV Faina, a Ukrainian-flagged weapons ship that pirates had held hostage for 134 days.

When Guyo asked his friend who the man was, he answered, “These are Muslim brothers. Don’t worry about where the money comes from. You’ll get your fee.”

“I expect this is pirate money,” Guyo said in an interview. “Kenyans don’t have this kind of money.”

With such riches on the table, experts said, pirates are unlikely to abandon the business anytime soon, despite worldwide condemnation and an international fleet of warships patrolling the Indian Ocean.

Some, like Samo, are cashing out, however.

He’d been working as a dockhand in Bossasso last year when he was recruited into a pirate gang and tasked with guarding hostages. After two jobs, he’d had enough of the searing heat and heart-pounding risk. He feigned illness and walked away.

He proposed to the mother of his young child and spent $5,000 on their wedding. He assuaged his parents’ anxiety about his career choice by buying them two modest homes and handing over most of his earnings.

Then, with $15,000 in his pockets, he set off for Eastleigh, where he’s renting an apartment with three other former pirates and trying to find his niche.

One day he visited a clothing shop that a slightly older pirate he knew had acquired recently. Samo scanned the neat aisles with their colorful fabrics and tried to imagine his future.

“It was nice,” he said later. “The guy sells ready-made men’s clothes from Dubai. There was an old man running the store, maybe his relative.

“It looked like a nice business. Something to think about.”

Source: MCCLATCHY NEWS

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar