U.S. trying new approach in Somalia to fight insurgency

Bartamaha (Stuttgart):- In the coming months, the U.S. will begin direct engagement with leaders of two northern Somalia breakaway regions with the hope that those political ties can stem the radical insurgency that threatens to spread beyond the lawless parts of southern Somalia, according to State Department officials.

Bartamaha (Stuttgart):- In the coming months, the U.S. will begin direct engagement with leaders of two northern Somalia breakaway regions with the hope that those political ties can stem the radical insurgency that threatens to spread beyond the lawless parts of southern Somalia, according to State Department officials.

The effort marks a significant policy change toward Somalia, which has become a safe haven for the Islamic insurgent group al-Shabab, an al-Qaida-linked faction that has been battling the weak, U.S.-backed central government.

In the last two years, the U.S. has spent more than $200 million trying to bolster Somalia’s Transitional Federal Government. And while that support will continue, the U.S. also will engage with leaders in Somaliland and Puntland as it looks to build on those regions’ relative political and civil stability.

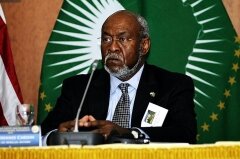

The U.S. will provide assistance that strengthens the regions and prevents them from being “pulled backward” by an al-Shabab incursion, Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Johnnie Carson told Stars and Stripes during a visit to U.S. Africa Command headquarters in Stuttgart last week.

“We want to encourage the TFG to be more than just a government in name only,” Carson said.

Working with groups in Somaliland and Puntland will help achieve “poles of stability that will create the kind of environment that will bring about more progress in dealing with radical extremism of Shabab,” Carson said.

Carson said the U.S. would not establish formal diplomatic relations with the two entities nor recognize their independence, but would help their governments with agriculture, water, health and education projects. By doing so, the U.S. hopes to shield these regions from the influence of al-Shabab, which seeks to impose its own harsh form of Sharia law across Somalia.

However, some Africa experts believe that the new approach is unlikely to quell any of the violence in the contested southern part of the country. It also is unlikely to spur reform within the country’s weak government.

“I’m not sure if investing more in the north helps secure the south … or furthers the goal of a united Somalia,” said Richard Downie, an Africa policy analyst with the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “But that goal is so far off right now as to be unobtainable, so the new focus I think is more on the short to medium term.”

The U.S.’s two-track approach is more a reflection of the incompetence of the TFG than a recipe for uniting Somalia, Downie said.

“It doesn’t make sense to have all the policy eggs in one basket,” he said.

Somaliland declared independence in 1991, and Puntland declared itself an autonomous state in 1998. While each has established its own political and law enforcement institutions, no other nation formally recognizes them.

But these territories could serve as bulwark against al-Shabab, according to Carson.

The decision to engage with other political elements in Somalia — other than the TFG — could signal a willingness for the Obama administration to adapt as the U.S. grapples for ways to contain the growing threat from groups like al-Shabab.

“I think it is a positive development, but like all policies, the devil is in the details,” said Ken Menkhaus, a leading Somalia scholar from Davidson College in North Carolina.

While U.S. development agencies and others in the international community have done work in Somaliland before, direct political engagement is something new. The challenge will be making sure that America’s involvement with Somali leaders outside the TFG doesn’t undermine efforts to build up a central government, according to Menkhaus.

“But if it’s done correctly, it reinforces the central government,” he said, adding that the policy shift will be unlikely to include a U.S. military component.

Support for the TFG remains the first priority, Carson said.

The African Union’s contingent of more than 7,000 troops, mainly drawn from Uganda, which protects the fragile TFG from being overrun by insurgents, will continue to receive U.S. backing, he said. Meanwhile, U.S. Africa Command continues to provide training and logistical support to deploying AU forces.

However, the Somali government needs to do more to bring together different factions in the country, according to Carson.

While there are no concrete initiatives yet, U.S. officials will begin to meet on a periodic basis with government officials from Somaliland and Puntland to discuss development issues, including health, education, agriculture, and water projects, to help ensure their capacity to govern and to deliver services to their people.

In addition, Carson said the U.S. will look to engage with smaller groups — clans and sub-clans — which deliver services to the population and oppose the ideology of Shabab, but are not aligned with the TFG.

For 20 years Somalia has been without a functioning government and during most of that time, the international community has been disengaged.

Ever since the deadly Battle of Mogadishu in 1991, which left 18 U.S. soldiers dead, the U.S. has had a largely hands-off policy toward Somalia. By 1992, all western troops pulled out of the country and diplomatic and development work was limited. However, during the past couple of years, that has been slowly changed as new threats have emerged.

“We’ve seen this localized cancer become a regional cancer,” said Carson. “We also see outflows of small arms across the border, feeding criminality and lawlessness.”

And with the influx of foreign fighters who are taking up arms alongside al-Shabab, including some Americans of Somali descent, the cancer has “metastasized” into a global malignancy, Carson said.

The long-term goal of one Somalia operating under something that resembles a democracy is a long way off, Carson acknowledged.

“It is first stability,” he said. “Second, it is to help create the conditions and environment to end the recurring cycle of humanitarian disaster and create an environment where development can take root.”

But while Carson will not say it, the TFG is probably not the political entity to bring that about, Downie said.

The decision to work with other political groups is a sign that the U.S. is getting more pragmatic in its approach, broadening what has so far been a narrow strategy, he said.

“It reflects the fact that the TFG is probably a doomed project,” Downie said.

=========================

Source:- stripes.

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar