Twenty-nine young Somali men – all from Ontario – have been killed

Somali-Canadians caught in Alberta’s deadly drug trade

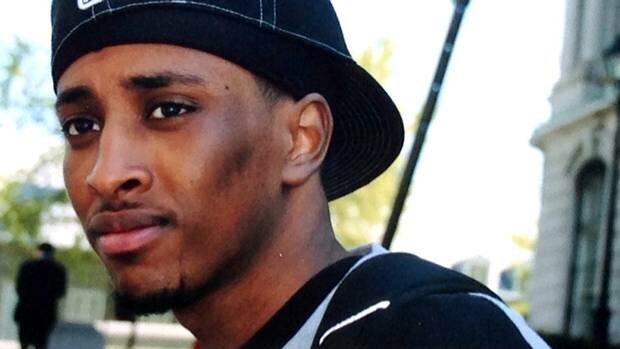

EDMONTON — Four months after he left Toronto, 21-year-old Abas Abukar was dead.

EDMONTON — Four months after he left Toronto, 21-year-old Abas Abukar was dead.

On Halloween morning in 2008, the former Humber College student’s body was found in Northmount Park, a wooded area in this city’s north end. Abukar had been shot a few hours earlier, an autopsy concluded. He was victim number 19.

A month later, Abdulkadir Mohamoud, 23, was found stripped, beaten and shot to death in a park. He, too, had moved from Toronto, about two years earlier.

That same day, Ahmed Mohammed Abdirahman, 21, was gunned down outside a seedy townhouse complex. They became victim numbers 20 and 21. Eight more would be killed after that.

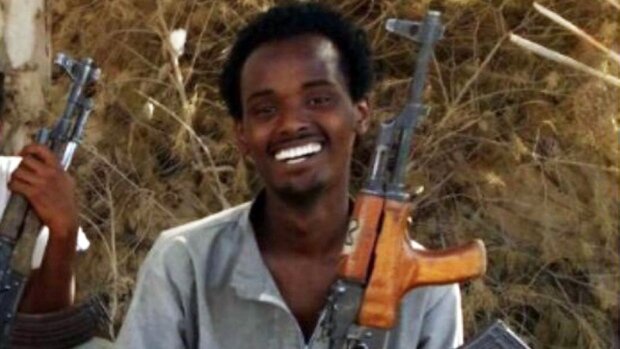

Since the summer of 2005, 29 Somali-Canadians ranging in age from 17 to 28 have been murdered in Alberta, in what police are calling an escalating gang and drug turf war amid the province’s booming oil economy. Some, however, have simply been killed in the crossfire, a situation of hanging out with the wrong people at the wrong time. The killings have occurred primarily in Edmonton, Calgary and Fort McMurray.

The victims were all from Ontario, mostly from the Toronto area, and almost all were either born or raised in this country.

Some moved to Alberta with their parents who, faced with an unemployment rate of 22 per cent in Toronto, the highest of any ethnic group, sought legitimate high-paying jobs while their kids succumbed to the lure of easy drug money. At least half, according to news reports, were known to police, in some cases small-time drug peddlers in Ontario who moved west to make better money in a lucrative drug market.

Edmonton police Chief Mike Boyd says his officers are working closely with investigators in Ontario cities to track the movement of gang members and drugs between the two provinces. But so far arrests have been made in only one case and members of the Somali community, having fled their own war-torn country, are growing anxious.

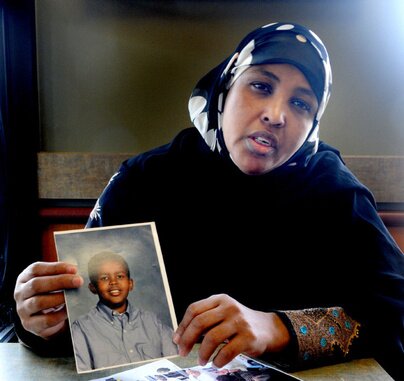

“I wish we had never moved to Edmonton,†says Faduma Arab, Mohamoud’s mother, who has since moved back to Toronto with her five other children.

“My son might have still been alive.â€

——————

Drug trafficking is dangerous anywhere but in Alberta, Canada’s most prosperous province, it has become increasingly more perilous.

In Alberta, the drug business is worth over $5 billion annually and is controlled by well-established gangs such as Hells Angels, native gangs and Asian triads. According to criminal experts, the ‘newbies’ — what the Somali-Canadians are called — are running headlong into other groups, rubbing people the wrong way and triggering turf wars in which they are coming out the losers.

Edmonton police and criminologists suspect Somali-Canadians aren’t even part of true gangs with guns and backup — just young naïve men in loosely organized groups.

Some Somali-Canadians have been recruited by other gangs and are being used at the lowest level as peddlers or mules to deliver drugs, says William Pitt, a former RCMP officer and now a professor of criminology at Grant MacEwan College in Edmonton.

“That makes them a disposable commodity — if the police get them, they don’t know much or have large quantities (of drugs) on them; and if they die… they are no loss to the gangs,†he says.

Gang war has hit Edmonton streets before.

In the late 1990s, Vietnamese gangs in the city battled each other and other crime groups to gain a slice of the city’s drug trafficking, prostitution and gambling. At least 10 people were killed over five years.

Somali-Canadians are easy targets: they are a small Black minority, the largest African group in Edmonton; they typically don’t carry guns; and they likely don’t know the nuances of the established drug trade, says Cathy Prowse, a former police officer, gang expert and criminal anthropologist at Mount Royal University in Calgary.

“There are some rules among gangsters… you never encroach on anyone’s territory, never steal others’ clients or drastically change the price,†says Prowse, who retired from the Calgary Police Service after 25 years.

The new kids on the block aren’t familiar with such subtleties.

“Young people also think they can make some money (in drugs) and get out if there are any problems,†says Prowse. “They are delusional. It’s easy to get in, tough to get out.â€

——————

“Come work for me. You’ll be rich,†says a tall man with a goatee, flashing a wad of notes at the three young Somali-Canadian men.

“It’s easy money.â€

Jamal Yusuf, 16, a student at J. Percy Page High School in southeast Edmonton, says he had heard of teenagers being offered money to peddle or deliver drugs, such as crack cocaine and heroin, but it was the first time he had been approached.

It was during a house party last summer — a K’naan number was blasting, Yusuf was sipping iced tea and grumbling about homework when the stranger made the offer.

Speechless for a moment, Yusuf says he smiled and declined.

He has been approached at least half a dozen other times with similar offers since moving from Toronto with his family in 2007. Each time, he has refused.

Yusuf, an easygoing teen with a quick smile, knows the dangers of the drug-related business, but says he wonders why others haven’t noticed the spike in funerals. “Everyone knows what’s going on… I don’t know why people still get involved.â€

But according to one small-time drug dealer on the streets of Edmonton who gave his name as Bilal Ahmed, the lure of easy money is difficult to resist.

——————

Ahmed, 19, says he grew up in Toronto’s Kipling and Rexdale Aves. area and moved to Edmonton in 2007 along with his older brother. He never sold drugs in Toronto, he says, but was peddling ecstasy pills within weeks of arriving in Edmonton.

Someone he knew was selling cocaine and offered him the pills to sell, which go for $5 to $20 each. The money was too good to refuse, he says. On a good weekend, he claims to make as much several thousand dollars, although criminologist Pitt says a mid-level drug dealer can make up to $10,000 selling coke or heroin in a single evening. Ahmed says it is also an easy way to make friends, blend in with the crowd, gain acceptance.

Ahmed doesn’t know when or why the violence started but it hit home on Nov. 29 last year when his cousin, Robileh Ali Mohamed, 23, of Ottawa, was killed near a Somali restaurant in downtown Edmonton.

“I thought I was going to be next…â€

Somali community leaders in Alberta say many victims appear to be related or knew each other beforehand; indicating one may have lured the other into the drug trade. Just last month, two cousins, Saed Adad, 22, and Idris Abess, 23, both from Toronto, were found dead in a Fort McMurray apartment.

——————

After his cousin’s death, Ahmed fled to Calgary, but returned two months later and is back selling on the streets. On this particular night, it’s about 2 a.m. and –10 C. The street lights are blazing at 107th Ave. near 105th St., close to the downtown core and its shiny corporate high rises, and a block away from a police station. The traffic never stops on the street, where hookers and pimps are known to hang out, and drugs are just a phone call away.

Ahmed, dressed in baggy jeans, a black sweatshirt and an Oilers hat, is sitting in a black Honda Civic in a shopping plaza parking lot where large billboards advertizing a nightclub, a liquor store and a massage parlour jostle for attention.

He’s waiting for a pick-up.

At 2:15 a.m., an SUV pulls up and the driver rolls down a window. The man nods and Ahmed steps out to meet him. Within a minute, money and pills have exchanged hands.

A year ago, Ahmed would have been cavalier — he says he may have hung around for another deal. Now he delivers pills to people he knows well and never stays in one place for long.

He is careful about his movements, never really feels safe. “It’s gonna get bad… like s**t… I’m ready to run back to Toronto,†he says.

—————

Edmonton’s Somali-Canadian community, pegged at 12,000 people, is the largest outside Ontario.

It is now under intense scrutiny, says Mahamad Accord, executive director of Edmonton’s Alberta Somali Community Centre. What angers him is when people call the murders a Somali problem. “It’s not — almost all of these men were born and raised in Canada,†says Accord. “It’s got nothing to do with their ethnicity.â€

He acknowledges too many young men are being drawn to crime but says “marginalization combined with a lucrative drug trade in an oil-rich economy has drawn these young men.â€

And, he adds, Alberta is less tolerant of diversity than Ontario. “If you are a person of colour, you will be treated differently… doesn’t matter whether you were born here or in Africa.â€

Accord and Ahmed Hussen, president of the Canadian Somali Congress, who met with police and Somali community groups in Alberta late last year, say they are trying to educate people and find ways to help Somali youths fit in by starting up homework and sports clubs.

A year ago, faced with criticism over the handling of the murder investigations, Edmonton police assigned Sgt. Patrick Ruzage and Const. Ken Smith, of the city’s gangs and drugs squad, as community liaison officers. Ruzage was sent to Ontario for a week to learn from Toronto police how to work with the Somali community. The two officers spend time mingling with the teens and organize friendly soccer games to try and build trust with the families.

“We are educating them… telling them how they can call Crime Stoppers, help solve a crime and stay anonymous,†says Smith, admitting there has been little success so far. “People are terrified of being snitches and then getting targeted.â€

There have been a couple of small victories. The officers, both of whom are black, have been approached by a few young Somali-Canadians about how to become police officers.

—————

Faduma Arab has sworn off Edmonton. Just talking about the time her family spent there chokes her up and her eyes fill with tears.

“I wish we had never moved there… I lost my son there,†says Arab, who now lives in a highrise in south Mississauga.

She phones the detectives on her son Abdulkadir Mohamoud’s case every week; she flies there every few months to see if there is any progress.

“Abdulkadir did not traffic drugs. He was the kind of a son who would clean up the house and cook if I wasn’t there.†She pulls out photos, school report cards of Mohamoud — he got straight As.

One of her younger sons concedes Mohamoud may have hung out with “the wrong people†and was targeted. “I don’t think he even knew that,†says the 17-year-old who did not want his name published. “My brother was a role model for all of us – we looked up to him.â€

He never wants to return to Alberta. “I can’t even remember the number of times I was chased from school because people thought I would have drugs… because I’m Somali.â€

Mohammed Aden is another devastated parent trying to make sense of his son’s death.

Abas Abukar was only three when the family moved to Canada in 1991 and settled in Etobicoke. He enrolled in the business program at Humber College and worked at Home Depot and Rogers in summer.

He moved to Edmonton in June 2008 “because he wanted to earn tuition money,†says Aden. Abukar had heard from his friends about well-paying jobs and wanted to spend a year working. “I didn’t want him to go… but his words were: I’m 21, I’m a man. I can do this,†says Aden, adding that he spoke to his son every day.

And then one day, he got a call: his son was dead

For the four months that Abukar was in Edmonton, he lived with his sister and her husband. She was pregnant and visiting her parents in Ontario when he was killed. She has since refused to return to that city and her husband has found a new job in Toronto.

“They were shattered,†says Aden. “…we were all broken.â€

_____

Toronto Star

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar