Toronto school board sets higher improvement targets for students based on race, sexual orientation

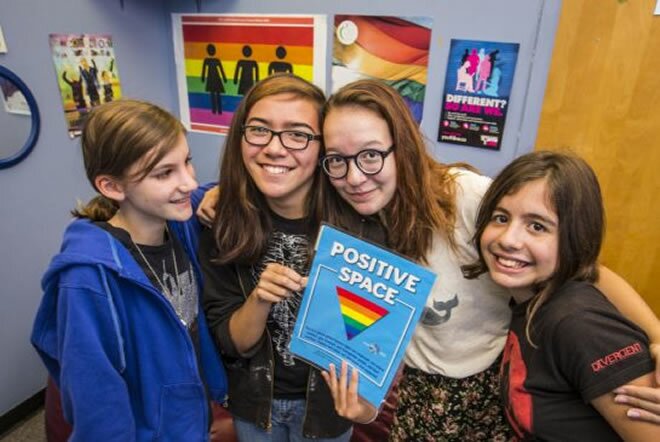

Students Charlotte Sulek 12, Nara Wrigglesworth, 13, Stella Racca, 13, and Irina Babayan,12, are members of the gay-straight alliance of Westwood Middle School, and they meet in the school’s Positive Space area together. The need for these bully-free zones has been proven by the Toronto District School Board’s detailed student survey.

For the first time in Ontario, a school board has set a different — and higher — target for raising the marks of students who are black, Spanish-speaking, aboriginal, Portuguese, gay or lesbian, than the target for its students overall.

The Toronto District School Board has pledged to boost the test scores and report card marks of students in these groups next year by 15 per cent compared to 10 per cent for all students, in a bid to shrink the learning gap it has found these students face and help them succeed at the rate of their classmates.

But such nuanced, colour-coded, even sexuality-based planning is possible only because of the goldmine of demographic data Canada’s largest school board dares to collect from its 200,000 students.

It showed, for example, that 32 per cent of students who identify as LGBTQ don’t graduate from high school, compared to 22 per cent of those who say they are heterosexual. And nearly half of LGBTQ students, 46 per cent, did not apply to college or university in 2012, compared to just 32 per cent of their straight classmates.

Call it the long-form census of the education world, and it, too, comes with controversy — revered by supporters, but dismissed by critics as intrusive and even stigmatizing.

“But everything we do to move students forward comes out of our census data, even at the highest level. We’re the only board in the province that sets different achievement targets for black, Portuguese, Spanish students, aboriginal and LBGTQ,” said Jim Spyropoulos, the TDSB’s executive superintendent of equity and inclusive schools. “This is a bold move.”

The board’s sweeping 40-question student survey drills deep into a student’s background and home life (identified by code number, not name, to protect privacy) and then links that information to the student’s marks and how they feel about school, to produce the mother of all flowcharts into how demographics can shape learning.

This deep level of data is the extreme example of a trend that is starting, gingerly, in schools across Canada.

Ontario now requires all boards to ask First Nations students to self-identify so educators can track what kind of support best helps them engage with school.

Nova Scotia now asks black students to self-identify for the same reason, and has begun analyzing test scores by neighbourhood income level.

Ontario’s testing body, the Education Quality and Accountability Office, has long broken down results for English language learners, boys and girls, and students with special needs.

A network of educators based at York University is running a “demographic data and student equity project” to encourage boards to collect this kind of information and offer tips on how to comply with human rights and privacy laws.

Ontario’s Ministry of Education now mentions “demographic data” in its vision statement, although it stops short of requiring boards to collect it.

The Peel District School Board is preparing a detailed demographic and attitudinal survey of its staff, though not students, next fall.

The TDSB survey probes deeply into a student’s life. There are 40 check-off boxes for cultural background, 12 choices for family make-up and 10 selections for sexual identity for students in Grade 7 and up. The survey also asks eight questions to determine how welcome students feel at school, plus questions on their home life such as “Do you take piano lessons?” and “Who helps you with homework?” The survey is then cross-referenced with students’ marks.

Yet such complex surveys are still a tough sell, even though the two boards that use them, Toronto and Ottawa, relish the findings and community groups across the province are clamouring for more boards to get over their fear and start using them.

It’s a tool some educators believe Queen’s Park should make mandatory.

“Because we know what the gap is with certain subgroups, setting the same improvement target for everyone would just keep all groups moving forward in lock-step and fail to narrow the gap,” said Spyropoulos. He points to a string of new programs this fall, sparked by the data, designed to help boost the engagement of these subgroups. The new programs include an entrepreneurial program for First Nations students and new Africentric lesson plans at the seven high schools and 10 elementary schools in Toronto with the highest percentage of black students.

Comments about being bullied from the first small batch of students to identify as LGBTQ helped prompt the board to promote more bully-free “positive spaces” and continue its support of gay-straight alliances.

“People at other boards often say to me, ‘We don’t need to spend money to find out this stuff; we already know our kids,’ ” Spyropoulos said. “But do we always know? You might assume a high school in an affluent community wouldn’t need a breakfast program, and then you ask them and find out 100 kids come to school hungry each day.

“With our census, it’s not just guesswork, it’s not about using city data, it’s not about relying on the government census — we have the information in-house.”

Moreover, in an era of accountability, Spyropoulos said it’s helpful to be able to point to the numbers when deciding whether to keep funding a program.

But not everyone has hurried to follow suit.

The York Region District School Board was poised to launch a similar survey of its 120,000 students in May — four years in the planning, with wide community support and other GTA boards watching closely — when it pulled the plug after some trustees expressed concerns about privacy and the cost.

Board chair Anna DeBartolo insisted the survey is just on hold until after the Oct. 27 election when trustees can get more details on which questions will be asked and how the board will protect students’ privacy.

“It really wasn’t on the trustees’ radar until this year and once it was, we decided we needed to have a more wholesome discussion,” said DeBartolo, adding she is “okay with asking these kinds of race-based questions; they give us a lot of information from students.”

Had York’s survey been circulated to students in May, as staff had planned, the board would be crunching numbers by now.

“There were going to be two questions on homelessness that we were really pumped about because we have no data on youth homelessness right now. Kids are often too embarrassed to admit they have nowhere to go,” said Michael Braithwaite, executive director of 360 Kids, an agency that helps homeless youth in York Region.

“Teachers can’t always tell that a kid who falls asleep at his desk may have spent the whole night walking around because something happened at home and he had to leave,” said Braithwaite. But if you ask, you might find out, he said, and get a clearer sense how to help.

“I hope the survey really is just on hold,” said Braithwaite. “We were disappointed at the delay.”

Cecil Roach is the York board’s superintendent of equity and engagement and a strong champion of collecting data.

“The things that are important are the things we measure, and you need to know who your students are. You cannot fully talk about supporting students unless you’re able to peel back the onion in order to see the inequities.

“You have some folks who say, ‘I don’t want to segregate kids by social identity,’ but that’s ridiculous,” said Roach. “We already know gay kids are more prone to suicide, but a lot of our knowledge is anecdotal. We need to know who our students are.”

York University education professor Carl James is such a believer in the value of gathering student data he has created a network of school board officials from Toronto, Peel, York Region and Ottawa to study the issue.

He would like to see Premier Kathleen Wynne call for a “learning gap strategy” like the one she requested this week to close the wage gap between men and women, and for this, surveys would be key.

“Such data would yield very rich information for the province,” said James, “and I would argue it would be of tremendous social and economic benefit.”

A spokesperson for Education Minister Liz Sandals said Friday her government is committed to have school boards “regularly use high-quality data and ongoing research to measure progress and guide programming,” especially after the scrapping of Ottawa’s long-form census, but “it is too early to tell what that will look like.”

But detailed surveys won’t be easy. A fierce split erupted this spring among Toronto’s Somali parents when the TDSB survey showed Somali students have a 25 per cent dropout rate, 10 points higher than the board average. While some Somali parents welcomed the information and joined a task force to examine solutions, others called it unfair labelling.

“These numbers can lead to uncomfortable conversations, especially about race and also sexual orientation,” admitted Spyropoulos, “but they’re conversations we need to have.”

• 75 per cent of children of professional parents say they feel they belong at school, compared to just 65 per cent of children of parents in unskilled jobs

• 79 per cent of black students say their school offers sports they like, compared to just 65 per cent of East Asian student

• 80 per cent of students live with two parents at home and one-third of families have three or more children

• 56 per cent of elementary students have at least one parent with a university degree

• 28 per cent — the largest proportion — of children from JK to Grade 6 live in families with annual incomes of less than $30,000

Source: Toronto Star

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar