The compass fails

ACCORDING to a cable leaked last month, the European Union’s man in Ethiopia told his masters that “basic human-rights abuses are being committed by the government on a daily basis” and “the EU must respond firmly and resolutely.” That was in 2005. Neither the EU nor any other Western donor has done anything of the kind. The United States, Germany and Britain have continued to pour money into the country despite the arrest of opposition politicians on trumped-up treason charges, the harassment of ordinary citizens, the curbing of internet access, and heavy spying on universities and workplaces. Sweden is one of the few donors that publicly raises civil liberties.

ACCORDING to a cable leaked last month, the European Union’s man in Ethiopia told his masters that “basic human-rights abuses are being committed by the government on a daily basis” and “the EU must respond firmly and resolutely.” That was in 2005. Neither the EU nor any other Western donor has done anything of the kind. The United States, Germany and Britain have continued to pour money into the country despite the arrest of opposition politicians on trumped-up treason charges, the harassment of ordinary citizens, the curbing of internet access, and heavy spying on universities and workplaces. Sweden is one of the few donors that publicly raises civil liberties.

When outsiders do bring up such issues, Meles Zenawi, Ethiopia’s prime minister, responds tartly that, with famine again stalking the Horn of Africa, the right of people to food, shelter, a job and indeed to life itself depends on the stability of the state. To challenge this is sabotage.

Paul Kagame, president of Rwanda (another country where past horrors tweak Western consciences) is similarly defiant. Asked in Paris this week about his human-rights record he replied: “I don’t know what you are talking about.” Yet several Rwandan military officers, and a few opposition leaders, have died mysterious deaths; other senior figures have been jailed on charges of historical revisionism or sedition. Mr Zenawi and Mr Kagame both enjoy Western favour; they are ex-rebels who run their countries cleverly and ruthlessly, with contempt for the strictures of campaigners such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. Both men are adept manipulators of Western guilt, and like many leaders in such countries, they know that the rise of China as an alternative patron makes it easier for them to cock snooks at critics.

If Western largesse brings little leverage over such behaviour, opprobrium also carries little clout. The current, elected leader of the African Union—supposedly a guardian of the continent’s conscience—is President Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea, a venal strongman who has failed to spread his oil wealth. This week he played host to President Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea, a barefaced dictator who has muzzled the press and ravaged a generation of young men. Both are seen by Western governments as pariahs, but neither cares.

Twisting the spring

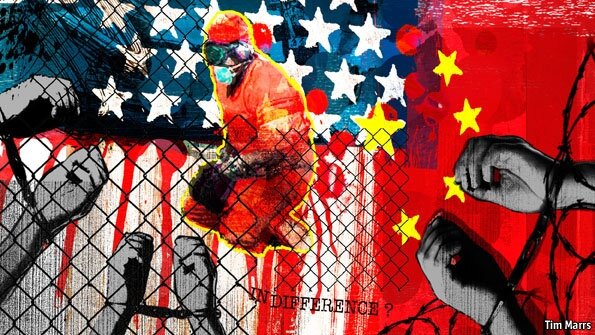

This depressing picture is not confined to Africa. Freedom House, a New York-based body that monitors a range of political and civil rights, reported that 2010 saw a net decline in liberty across the world for the fifth year in a row, the longest continual decline in four decades of record-keeping. It noted more “truculence” among authoritarian rulers. That was before the Arab spring—which, heartening as it was to believers in freedom, prompted many Asian regimes, from Iran to Uzbekistan to China, to intensify repression and curb the media.

For their part, Western governments have become shy about spreading the idea that certain human rights, enshrined in United Nations conventions, are universal. When they do preach that message, it often falls on deaf ears. The human-rights industry is alive and well, but deeply divided. A cacophony of rival talkfests in New York in the coming days will include a UN conference on “racism”—known as Durban III because it follows a meeting in South Africa in 2001—that will feature much tub-thumping from anti-Western leaders.

America, Canada and at least six EU countries will boycott the conference on the ground that it targets Israel far more than any other country. One bunch of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) supports the shindig. Another lot opposes it, blasting the UN for being hard on Israel and soft on anti-Western despots. Thor Halvorssen, founder of a gathering called the Oslo Freedom Forum, calls Durban III “the last act in a tragicomedy” that demonstrates the UN establishment’s subjection to “despotic regimes which speak pretty words about human rights while they kill, torture or jail their opponents.”

This broken consensus about which rights, and whose rights, matter most contrasts sharply with the halcyon days of 20 years ago. As democratic Russia emerged from the Soviet chrysalis it tried to outbid the West in its fervour for human rights. The talk was of a new liberty-respecting, democratic space stretching, at a minimum, from Vancouver to Vladivostok. Only a decade ago, the Clinton administration—flush with confidence after enlarging NATO, defeating Serbia’s ethno-nationalism and promoting free trade—spoke as if the final triumph of liberal, rights-observing democracy was just a matter of time.

The shift stems partly from the Western powers’ loss of global heft. Some powers now emerging—India, Brazil and South Africa—are robust democracies, but they still resist the idea of teaming up with the old West to back liberal values, notably in votes at the UN. Even in Western corridors of power, where promoting civil and political rights still commands lip service, other priorities have blunted zeal. Trade with China is one; the need for ex-Soviet states’ help over Afghanistan is another. American government efforts now focus on narrower areas: religious freedom, people trafficking and bonded labour, and (pace WikiLeaks) internet freedom.

Catherine Ashton, the EU’s foreign-policy chief, issues almost daily scoldings to nasty regimes. But tyrants hardly tremble at her tongue-lashing, or see any consistency in the application of tougher measures. Sri Lanka shrugged off criticism of its treatment of Tamil civilians in the war. EU sanctions on Uzbekistan, imposed after a massacre in 2005, were largely lifted in 2007, amid German hopes (which proved futile) for “constructive engagement”. A recent closed-door consultation between EU officials, NGOs and the Beijing authorities was overshadowed when a feisty New York-based NGO, Human Rights in China, was kept away. The stalling of EU expansion has dented its soft power to its east. The show trial of Ukraine’s opposition leader Yulia Tymoshenko has drawn no serious sanction from the EU. Both sides care more about trade.

Nor does the West’s moral clout in north Africa amount to much. A history of cosy ties with corrupt autocracies in Egypt and Tunisia and (for a time) Libya have left people suspicious of Western motives and unwilling to be lectured. Indeed, half-hearted human-rights diplomacy can backfire nastily. Criticism merely alienates incumbent regimes. But when they fall, the new lot say that by doing too little the West tacitly colluded with their torturers.

Yet promoting human rights in thick-skinned countries is not a hopeless cause. All tyrants want things from the West—from a haven for their ill-gotten gains (see article) to recreation for their families. When access to these goodies is withdrawn, it can send a powerful signal. In recent days, for example, New York’s Fashion Week cancelled a presentation of haute couture designed by Gulnara Karimova, the Uzbek ruler’s daughter after NGOs drew attention to her father’s human-rights record. Under similar pressure, RBS, a British bank, vowed to stop raising bonds for Belarus, Europe’s “last dictatorship”, which has jailed dozens of political prisoners. In July the rock star Sting cancelled a concert in Kazakhstan in protest at the violent treatment of striking oil workers. That was the sharpest rebuke the regime had received for a long time.

All these involved a Western partner forfeiting something—from bond-management fees to music or fashion royalties—for the sake of principles. So far the people who sell sports cars to President Obiang have not shown such self-denial. But when anybody feels strongly enough about a cause to make a sacrifice, that compels a certain respect. Lofty, cost-free moral lectures count for less and less.

___

The Economist

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar