Stranded, abandoned, abroad

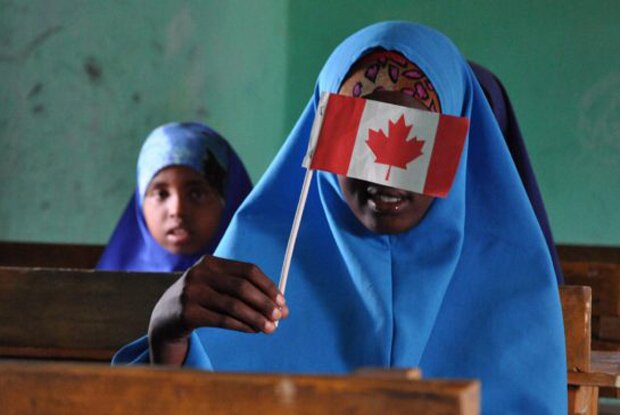

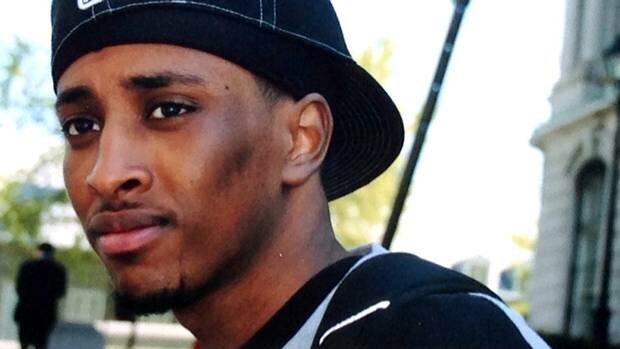

Anab Issa’s 25-year-old autistic son, Abdihakim Mohamed, is stuck halfway around the world in Nairobi, Kenya, stateless and without proper care, while she fights to prove he’s a Canadian citizen so she can bring him home.

Sound familiar? It’s yet another story of a lost Canadian, among scores abandoned by the federal government and dumped among the world’s stateless pariahs.

It’s been a frustrating, multi-year battle for Issa, and she’s terrified for her son’s safety. A big man who can turn aggressive when frightened, he’s been bloodied by street gangs and harassed by police in Nairobi. “If you run, they shoot at you,” she says.

Issa describes how she juggles two $9.30 an hour cleaning jobs to send much needed “bribe” money to Kenya. “Very sad, very desperate,” she says, by phone from her Ottawa home. “I am all the time afraid.”

Her Somali-born son is Canadian, living most of his life here until fate put him in a Kafkaesque situation in Kenya. When Issa tried to apply for a new passport for Mohamed in 2006, Canadian officials in Nairobi denied his identity.

In 2008, Passport Canada wrote to Issa to advise: “You are the subject of an investigation … concerning your involvement in attempting to obtain a passport for an impostor in the name of your son, Abdihakim.”

Just last weekend, Suaad Hagi Mohamud, 31, flew home to Toronto from three horrid months in Nairobi, after DNA testing finally proved to Kenyan and Canadian officials she wasn’t an impostor. The Canadian diplomat who handled her case was recalled from Kenya last week and Public Safety Minister Peter Van Loan announced an investigation. Mohamud’s home due to public pressure, and that same pressure might help Issa’s son. Late Thursday, a spokesperson for Foreign Affairs Minister Lawrence Cannon, touting how closely Ottawa “continues to work” with him, allowed that Passport Canada will issue a travel document once an application has been received.

“Another application?” says Issa incredulously. She’s cautiously optimistic, saying: “I get the passport, I believe it.” It’s unclear whether additional affidavit evidence is required on top of what she has already provided.

Sadly, the amateur-hour diplomacy of these cases appears the norm, not the exception. There are too many tales of discarded Canadians, stuck in foreign hellholes.

Reflect on Brenda Martin’s two years in a Mexican jail on a shaky money laundering conviction. Under a prisoner transfer agreement, Martin returned to Canada May 1, 2008 to serve her sentence, and was released from custody a week later.

William Sampson smeared the walls of his Saudi Arabian cell with his own excrement during 32 months in jail, tortured into confessing to crimes of terrorism and recanting only upon release in 2003. He saw Canadian diplomats as betrayers.

Abousfian Abdelrazik flew back to his family in Montreal in late June, after being stranded for six years in Sudan – including 20 months behind bars, where he was interrogated and tortured but never charged. Although a Canadian Federal Court judge expedited his return, he remains on the UN no-fly list and is still fighting to clear his name.

“I don’t think (the Conservative government) values Canadian citizenship,” says Liberal consular affairs critic MP Dan McTeague (Pickering-Scarborough East). “The moment you leave Canadian airspace, there’s a complete reversal of who you are as a Canadian, and you’re convicted by an Orwellian jury composed of cabinet.

“There is no form of accountability when it comes to consular services and it’s a secret approach to helping Canadian citizens. Canada won’t do what other countries do as a matter of course. Their attitude is, `Throw them to the lions.’ “

Cases are endless. Each day at noon, Jirina Kuliskova, a young Vancouver mother, keeps a vigil outside the Mexican consulate in Vancouver to protest the imprisonment of her husband, Pavel Kulisek, 43, in Mexico. A Czech-born Canadian citizen, he’s been in a maximum security prison in Guadalajara on drug-trafficking and organized crime charges for 17 months, without trial and without any show of evidence.

The couple, with daughters, Isabella, 7, and Annie, 5, had taken a few months off to live in Mexico, where Kulisek met alleged Tijuana Cartel thug Gustavo Martinez at a motorbike track. A YouTube video shows armed-to-the-teeth Mexican soldiers arresting several men, Kulisek among them, wan and blinking in cut-offs and flip-flops, replying to reporters: “From Canada … I’m on holidays.”

Kuliskova isn’t asking for proclamations of innocence, but pleads with Canadian diplomats to get involved. “I’m asking myself how long, or what else will I have to do, before somebody in the government is going to help me?” she says, on a website for her husband. “Am I asking too much? Is it too much for our government to apply pressure to the Mexicans so Pavel can receive a fair and speedy trial?”

McTeague unsuccessfully appealed several times in Parliament recently to Peter Kent, minister of state for foreign affairs, to “convey to the Mexican government some concern. … Canadians need to know that their government will protect them if they end up in trouble abroad – and this government has failed terribly at that.”

Toronto immigration lawyer Guidy Mamann shakes his head. “When a Canadian is in trouble, the clear message should be to err on the side of caution. But that’s clearly not the culture that exists among foreign service officers.”

What he found despicable in Suaad Hagi Mohamud’s case was “the Canadians sided with the Kenyans to bury her … The role of our government should be, at the very least, not to do harm to its citizens.”

Other countries act differently. It’s commonplace to witness Sweden, for example, pulling out all the stops to help Swedes abroad. It’s rarely so for Canadians. In Mexico in the late 1990s, Canadian officials hurried to agree with a Mexican suicide verdict after a Canadian was found hanged in a jail cell. By the time the British consul proved the feat was logistically impossible, the body had been cremated.

Mamann remembers his former life as an airport immigration officer watching Americans often react with outrage when stopped and questioned by Canadian officials. They came “with all six-guns blazing,” he says, “telling us we’d be soon hearing from their congressman or lawyers.”

There’s little rhyme or reason to be found in Canadian actions. Increasingly, there appears to be friction and confusion between the post-9/11, U.S.-style Canadian Border Services Agency, and Citizenship and Immigration Canada, with responsibilities ill-defined. CBSA is the big kid on the block. Several lawyers were baffled when the agency stepped in on the Mohamud case when they’d assumed CIC would do the heavy lifting.

Rules seem erratic. Sometimes DNA evidence is accepted; other times not. In the case of two women stranded in Buffalo, CBSA officials flatly rejected DNA evidence in a case that, by its nature, allegedly flouts Canadian law and the rights of their Canadian relatives.

Ethiopian citizens Sayoo Omar Abubaker and Fozia Mohammed Hassen, both mothers in their early 30s, are trying to enter Canada to apply for refugee status. Both say they face persecution for political activities in Ethiopia; government forces have already killed family members. Both qualify for entry into Canada under the Canada-U.S. Safe Third Country Agreement that allows only people with relatives in Canada to do so.

With the help of U.S. lawyers, they travelled to CBSA offices in Fort Erie, carrying DNA evidence of kinship to Canadian citizens. “They were told, `We have no protocol or procedures for DNA. We don’t deal with it,’” says U.S. advocate Peter Murrett, from Buffalo’s Vive La Casa refugee house.

Mamann last week filed appeals for both women in Canadian Federal Court. “The government turns a blind eye to its own law,” he says. “They don’t seem to have any interest in the truth.”

Not all cases of statelessness involve grimy foreign jails. Don Chapman, a B.C. rights advocate, estimates there are thousands of “Lost Canadians” stripped of their citizenship, either through arcane laws (despite a recent overhaul of citizenship legislation) or disregard by obdurate bureaucrats. “Right now, this government and, in particular, this immigration minister (Jason Kenney), are not doing justice to the reputation of this country,” Chapman says.

There are many examples, many defying logic:

- Two cousins were born two years ago, Lillian Miller in Germany and Casey Neal in Oregon. Lillian’s parents can obtain Canadian citizenship for her because a grandfather was Canadian. Casey’s parents are denied that right because her link to Canada lies with a grandmother. Chapman contends such decisions contravene a Supreme Court ruling against gender bias.

- Jane Cotton was born in Canada, lost her citizenship when she moved to the U.S. with her Canadian mother and English father but was repatriated after changes to the law. Now living in Ottawa, she can’t get citizenship for her son, James Pemberton, 18.

- Magali Castro-Gyr, 50, is 10th-generation Canadian, descended from the Daniels who arrived in Quebec in 1624. She’d already gone through four passports when, after living abroad with her Swiss husband, she discovered she not only couldn’t get passports for her two teenage boys, Julien and Brannen, but had lost her own citizenship. It’s been an 18-year struggle, at a cost of over $30,000 and forcing a 2003 move out of Canada after the government offered her only immigrant status, requiring her to sign a gag order to boot. She declined.

Finally last week, she was told a permanent passport is ready.

- Jackie Scott, 64, and living in B.C. found out she isn’t Canadian because she was born out-of-wedlock to a Canadian father and British mother. She, too, has fought for years and has been rebuffed several times in efforts to get a passport.

Meanwhile, Anab Issa will spend coming days waiting for good news. Her story began innocently enough when she brought her son to live with her mother-in-law in Somalia in 2004. She erred in bringing his passport back with her to Canada for safekeeping, placing her under immediate suspicion when it was found by officials at Pearson airport and confiscated. Still, no action was taken. By 2006, her mother-in-law was sick and Issa wanted to bring Mohamed home.

She accompanied him to Nairobi and sought help at the Canadian High Commission. “Every time she obeyed (the Canadian government), they moved the goal posts on her,” says Ahmed Hussen, national president of the Canadian-Somali Congress. “The most bizarre was after they told her they had an impostor in Nairobi, they actually asked her, `Can we have your help?’ He was her son.”

Neighbours in Nairobi try to protect Mohamed, says Issa. They tell police: “He’s a poor boy, he’s sick, please, please, don’t hurt him.” But there are no guarantees.

So what’s the solution?

Issa’s problems – along with those of other Canadians – could be eased with a clear protocol for identifying and protecting citizens, according to immigration lawyers. It would be a start.

It’s clear Canadians expect their embassies and consulates to work on their behalf and are outraged when, time after time, so little help is offered. When Canadian officials responded sluggishly to the 2006 murders of Thornhill residents Dominic and Nancy Ianiero in Mexico, readers inundated the Toronto Star with their own stories of outrage and neglect, although not so horrific, in foreign locales.

“Maybe it should be an election issue,” says Mamann, stressing it’s up to Canadians to demand the service they want from officials and set the rules for government. If they don’t get it, there’s always the democratic option of throwing the bums out.

“Perhaps some of the blame should be laid at the feet of the Canadian public,” Mamann sums up. “Too many citizens believe all these immigration and citizenship problems don’t affect them – until they do.”

Source: TheStar

By

Photo:

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar

From Mexico to Nairobi, they wait in vain for help from ‘amateur-hour’ Canadian officials

From Mexico to Nairobi, they wait in vain for help from ‘amateur-hour’ Canadian officials