Spaghetti at gunpoint

A life of travelling to war zones leads Paul Watson to conclude that food always tastes better when fear is on the menu.

Good eating on the roads I travel usually owes more to hunger, and a healthy dash of fear, than to the cook’s skills.

The squatting Afghan hawker’s liver kebab, cooked in clouds of roadside dust and served on a scrap of newspaper, isn’t seared into my memory by a special marinade or the chef’s deft turn of hand.

Forgiving the bits of carbonized meat, and grains of sand, it was the most memorable Afghan kebab among many because I felt so alive after running the Taliban gauntlet through southern Zabul province.

For thoughts of pure flavor, nothing beats the steaming slice of raw seal liver I ate off the tip of an Inuit hunter’s knife, as the blood of the freshly killed animal pooled on the white snow.

But that was more an hors d’oeuvre than a meal.

My most unforgettable meal was in Somalia, I’m sorry to say, in the middle of an epic famine.

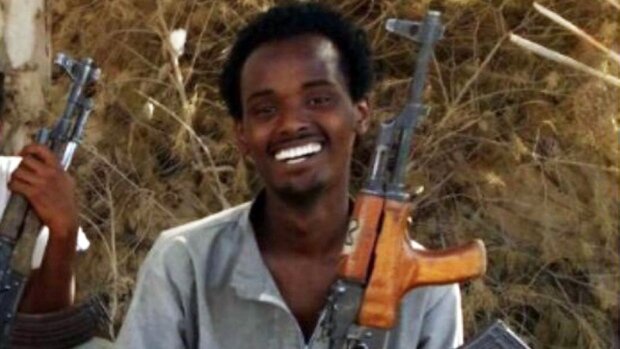

It was 1992, and the country had descended from civil war to anarchy. Gunmen were looting relief supplies and blocking aid deliveries in the hardest-hit areas.

I was working out of Baidoa, in south-central Somalia, where the starving died on the bare ground where they slept.

Each dawn, moving through moaning crowds waiting outside feeding stations, stepping over prostrate children or their parents, it was hard to know who had died in the night and who would soon awake.

We called it The City of Death.

The problem wasn’t a shortage of food, but the lack of security that the aid workers needed to feed the hungry without getting held up or killed.

In the blazing midday sun, unable to escape death’s stench, I had a choice between eating lunch or passing out. So I joined a couple of other Canadians at a gloomy pasta restaurant, a vestige of Italian colonial rule.

Even by Somali standards it was dark, lit only by slices of sunlight that broke through cracks and bullet holes. Not the kind of place where customers lingered.

When we finished our spaghetti, the only other patrons left were two Somali gunmen, their assault rifles propped against the back wall in deference to house rules.

They saw us pull out U.S. dollars to pay, grabbed their guns and levelled the barrels at our guts, demanding we empty our pockets and money belts.

I was more worried about my camera bag, which I tried to gently kick under the table. That started a tug-of-war between me and the closest robber, who grabbed the shoulder strap with one hand and aimed the rifle with the other.

The shouting roused our host from the kitchen. He must have imagined what the spilled blood, and lunch, of foreign customers would do to business. He bolted out to raise reinforcements.

The stickup men fled without a fight, leaving me high on the adrenaline rush of cheating death. An uninspired meal of spaghetti and meat sauce suddenly became a spiritual awakening.

So, when colleagues invited me months later for lobster in north Mogadishu, I gladly risked crossing the Green Line, where the most crazed Somali gunmen battled each other daily.

Fresh seafood, cold beer, great stories, all amid the shell-scarred ruins, with a view of the Indian Ocean.

Now that’s food to die for.

__

Toronto Star

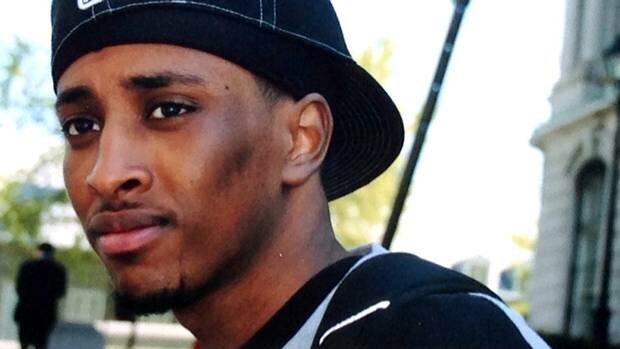

Paul Watson won a Pulitzer Prize for a photo of a blood-crazed mob in Somalia.

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar