Somalis fleeing to Yemen prompt new worries in fight against al-Qaeda

KHARAZ, YEMEN — Thousands of Somali boys and teenagers fleeing war and chaos at home are sailing to Yemen, where officials who have long welcomed Somali refugees now worry that the new arrivals could become the next generation of al-Qaeda fighters.

As the United States deepens its counterterrorism operations in Yemen, officials are concerned that extremists could find growing Somali refugee camps fertile ground for recruiting. U.S. and Yemeni authorities also fear that Islamist fighters from Somalia could slip into the country among the throngs of refugees, deepening ties between al-Qaeda leaders in Yemen and the particularly hard-line militants of Somalia.

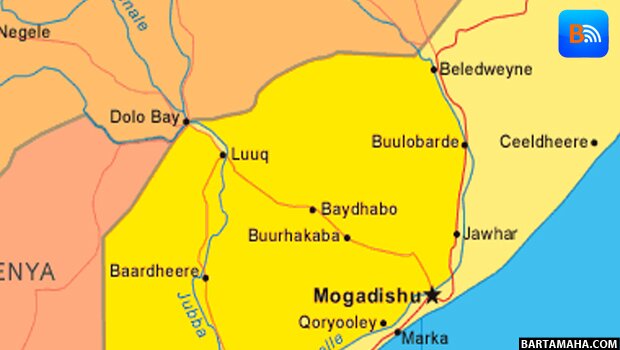

Fleeing a failed state for a failing one, the Somali youths arrive daily in this refugee outpost, which is filled with rickety tents and tales of misery, in the vast desert of southern Yemen. They bring stories of brutality and forced conscription by al-Shabab, an Islamist force battling Somalia’s U.S.-backed transitional government.

“They ordered us to fight the nonbelievers,” said Abdul Khadr Salot, 19, a burly ex-fighter with a thin scar across his cheek who escaped from a militant training camp. “Even if your father tells you to leave the Shabab, you must kill him.”

But this longtime haven is becoming increasingly inhospitable since the United States bolstered its operations here, largely in response to the Yemeni al-Qaeda connections of the Nigerian man who allegedly tried to bomb a U.S. airliner over Detroit on Christmas Day, and to the links of an extremist Yemeni American cleric to the Nov. 5 shootings at Fort Hood, Tex.

Yemen’s fragile government fears that Somali fighters from al-Shabab will swell the ranks of Yemen’s Islamist militants at a time when links between the Somali group and al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula are growing, according to Yemeni officials and analysts.

As it quietly wages war against extremists in the Arabian Peninsula and parts of Africa, the Obama administration could find itself confronting a unified, regional al-Qaeda on two continents. This would further stretch U.S. resources as Washington fights major conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. It could also push Yemen — beset by mounting internal strife, poor governance, extreme poverty and dwindling resources — even deeper into a downward spiral.

“Somalia for Yemen is becoming like what Pakistan is for Afghanistan,” said Saeed Obaid, a Yemeni terrorism expert who wrote a book on al-Qaeda’s Yemen affiliate.

Leaders of al-Shabab, which the United States has labeled a terrorist organization with links to al-Qaeda’s central body, said last week that they will send fighters to help al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. That prompted Yemeni Foreign Minister Abu Bakr al-Qirbi to issue a stern warning through the state-run Saba news agency that Yemen will not allow “any terrorist elements from any country to operate in its territory.”

In recent days, Yemeni security forces have staged raids on Somali refugee communities, detaining suspected loyalists of al-Shabab, which means “The Youth.” Overnight, an atmosphere of fear has gripped the community, which numbers more than 1 million.

“The climate has changed, and it is heating up,” Mohammed Ali, a top leader of the Somali community in the Yemeni capital of Sanaa, lamented over a glass of Somali coffee.

An estimated 74,000 African refugees, mostly from Somalia and Ethiopia, arrived in Yemen last year, 50 percent more than in 2008, according to statistics from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. UNHCR officials say 309 either drowned in capsized boats or were killed by smugglers.

In September, a gang of al-Shabab fighters grabbed 14-year-old Saber Ahmed at his father’s shop in Mogadishu, the Somali capital.

They blindfolded him and took him to a nearby militia base, he said. There, they brought out recruits he knew from his neighborhood, who urged him to join. The peer pressure didn’t work. Then, an al-Shabab commander gave him an ultimatum.

“He said, ‘We will kill you if you don’t join us,’ ” recalled Ahmed, tall and lanky with a soft voice and chiseled face.

After 20 days of training, he was sent to the front lines. Within hours, he said, a battle erupted; Ahmed was shot in the leg. He managed to crawl to his house. His father took him to a hospital. When Ahmed regained consciousness, his father gave him $100 and ordered him to flee to Yemen.

In the Somali port of Bossaso, he handed the money to a smuggler, who placed him on a crowded boat headed for a treacherous sea. As the boat neared Yemen, it flipped over. Ahmed swam nearly a mile to the shore. He later learned that seven passengers had drowned.

Ahmed’s experience is a familiar one, according to Somali community leaders and officials at the UNHCR, which runs the camp here in Kharaz. Parents often say they bring their children to Yemen to prevent them from one day joining al-Shabab. “It’s very easy to brainwash youth. They tell them, ‘We’ll give you money. We’ll give you power,’ ” said Rocco Nuri, a UNHCR official in Aden.

When told that former al-Shabab fighters were in Kharaz, Nuri expressed concern but said it was “impossible to monitor this” in an open camp where residents come and go freely. Nevertheless, he expressed confidence that the camp is not a haven or recruiting hub for Somali militants.

In Yemen, Somalis are worse off than Yemenis. Jobs are scarce. Thousands of Somali youths eke out a living washing cars. They sleep under trees and bathe in public water tanks. Most Somali refugees view Yemen as a transit point to richer nations such as Saudi Arabia. But in recent months, a war between the Yemeni government and Shiite Hawthi rebels in the north has stemmed the migration.

Salafist schools, which teach a puritanical brand of Islam, have attracted several hundred young Somali refugees with offers of free food and lodging, said Somali community leaders. They fear some could join al-Shabab.

“Some boys did return back to Somalia,” said Deka Muhamed, a Somali elder in Sanaa. “We’ve heard they’ve been killed, but we don’t know how or why.”

Yemeni officials, meanwhile, worry that al-Qaeda could lure Somali ex-fighters into their ranks with promises of money or aid. But so far, there has been no evidence of this, say Western diplomats and Yemeni officials.

In an audiotape last year, Osama bin Laden exhorted al-Shabab to overthrow the Somali government. Radical Yemeni American cleric Anwar al-Aulaqi, whom the United States has linked to the suspect in the attempted Christmas Day bombing and to the gunman charged in the massacre at Fort Hood, has also expressed support for al-Shabab.

Yemeni officials and analysts say there is regular communication between al-Qaeda militants in Yemen and al-Shabab. Last week, Somalia’s state minister for defense declared that Yemeni militants had sent al-Shabab two boats filled with arms. They have also traveled to Somalia to fight.

“Some elements went to Somalia. Some were killed there,” said Rashad al-Alimi, Yemen’s deputy prime minister for security and defense.

Foreign Minister Qirbi, in an interview before the failed Christmas Day attack, urged Western nations to provide greater support for Yemen’s coast guard to protect its shores from militants entering or leaving. “We also need better surveillance of refugees in the country,” he said.

‘All become suspects’

Many Somali refugees refuse to leave their houses at night, fearing they will be picked up in a security sweep. “Nobody carries a Shabab I.D. It’s not written on our foreheads,” said Ali, the community leader. “We have all become suspects.”

Most Somalis, he noted, practice a moderate form of Islam that stresses tolerance.

At the Somali Refugee Council office in Sanaa, more than 20 refugees have reported losing their jobs in the past week, said Mohamed Abdi Gabobe, its chairman. The council, he said, is planning a demonstration to show solidarity with Yemen, in the hopes that this will lessen the pressure on the community.

But many refugees are worried about their futures. They say they have become the latest victims in the U.S. counterterrorism campaign.

“When two elephants fight each other, it is always the grass that is destroyed,” said Sadat Mohamed Yusuf, a Somali community leader. “We are the grass.”

Source: The washington Post

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar