Somalia, Wobbly on Ground, Seeks Control of Its Airspace

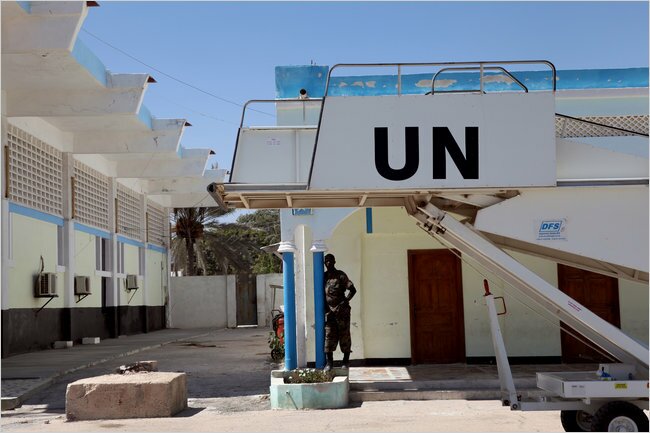

The United Nations controls Somalia's air traffic and collects its flyover fees, leaving little, Somalis say, to repair the decrepit airport in Mogadishu.

MOGADISHU, Somalia — With pirates running rampant offshore and Islamist militants boxing lawmakers into a corner of this bullet-ridden capital, the beleaguered Somali government does not control its land or its seas.

But Somali politicians are confident they can wrest at least one frontier from the grip of outside forces: the skies.

For almost 15 years, the United Nations has controlled Somalia’s airspace from a little office in Nairobi, Kenya, where an international staff of air traffic controllers sit quietly in front of computers to make sure the scores of commercial jets that crisscross Somalia each day — usually on their way to somewhere else — do not crash into one another.

Taking charge of this is far more than a matter of pride. Tens of millions of dollars in airline flyover fees have been handed over to the United Nations since the caretaker arrangement began, but Somali officials complain that very little of that has gone to Somalia itself.

So much of the money is spent paying the generous salaries of United Nations employees, they contend, that little is left over to train Somali aviation officials or repair the country’s decrepit airports. At Mogadishu International Airport, rats have chewed through the wires of X-ray machines, and chunks of concrete routinely break loose from the ceiling and crash down, frustrating Somali officials to no end.

“Definitely, we will reclaim that authority,” said Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, Somalia’s prime minister. “It’s very simple. The airspace belongs to the Somali people. We are a sovereign country. This isn’t just about the money.”

United Nations officials say they agree, in principle, with allowing Somalia to play a bigger role in managing its own airspace, but they are worried about handing over the keys to a complex and potentially dangerous operation to a government that is constantly teetering on life support.

Even in the little zone of Mogadishu that it loosely controls, the Transitional Federal Government of Somalia struggles to demonstrate that it can pay its own salaries and pick up the trash, let alone juggle several dozen jetliners hurtling through the air at 600 miles per hour.

“It’s fundamentally a question of safety and security,” said Denis Chagnon, spokesman for the International Civil Aviation Organization, the United Nations agency that took over Somalia’s airspace in 1996. Mr. Chagnon said that although the agency had stepped up in disaster zones before by, for example, temporarily managing the skies above Kosovo and Haiti, “nothing really compares to Somalia.”

“If you are going to hand over the control to installations in Somalia, you have to ensure that those facilities are up to par, that the personnel involved are well trained,” he said.

Talks have been going on between the two sides for months, but some Western diplomats are suspicious of the Somali government’s interest in the airspace fees. Transparency International recently ranked Somalia the most corrupt country in the world, and one Western diplomat contended that there was “a feeding frenzy now” because it is unclear how much longer the transitional government’s mandate will be valid.

Given the uncertainty over what will happen after that, some Somali officials are “going after any little pocket of money they can find,” said the diplomat, who was not authorized to speak publicly.

But the Somali officials counter that it is the United Nations that has been stealing from them.

“The U.N. has been using our money for luxury cars and villas,” said Capt. Mohamoud Sheikh Ali, who until recently was the general manager of civil aviation in Somalia. “They are looting our property.”

And therein lies another problem. Captain Mohamoud, a former Somali Air Force pilot who once crash-landed a Russian-made MIG on a Somali beach after he ran out of fuel, was abruptly dismissed in one of the frequent, wholesale change-outs of ministers and top civil servants in the endlessly bickering Somali government.

“We’ve been trying to find a transition,” said Álvaro Rodríguez, a United Nations official who works on Somalia. “But with the T.F.G. and all the staff changes, it kind of comes and goes,” Mr. Rodríguez said, referring to the Transitional Federal Government. In many ways, the fight over Somalia’s airspace is similar to the battle over its pirate-infested seas. The shipping lanes off Somalia’s coasts are vital to global trade, especially for oil tankers passing from the Middle East to Europe and the United States, prompting Western powers to send warships to patrol Somalia’s waters.

Because of Somalia’s strategic position at the crossroads of Africa and Arabia, about 90 flights enter its airspace every day. That traffic includes some of the world’s biggest airlines, like Air France and Emirates. And thanks to a little-known fact in the world of air travel, air navigation charges, every time a jetliner soars above this war-ravaged country — Air France from Paris to Réunion, Emirates from Dubai to Johannesburg, or El Al from Tel Aviv to Thailand, for instance — the authorities managing Somalia’s airspace get $275.

The Somali government used to collect those fees, now estimated at $4 million a year, but the government collapsed in 1991, suddenly leaving the airspace wide open.

The United Nations civil aviation authority stepped in to help, part of a huge peacekeepingmission. But when the peacekeepers failed to pacify Somalia, the flight information center was moved to Nairobi and the airspace fees were used to pay for the United Nations-run operation. As Captain Mohamoud pointed out, no Somalis appear to have been consulted.

Then again, nobody knew that Somalia would languish so long without a functioning government. So what was supposed to be a temporary caretaker arrangement for Somalia’s airspace is now pushing 15 years.

One of the main goals was to develop “an essential nucleus” for a Somali civil aviation department. But while Somalis have been hired to work in Nairobi, they complain of being treated like second-class citizens and say that few, if any, of them have been promoted to management positions — even though that was supposed to be a priority of the United Nations program. Many of the Somali employees make less than $1,000 per month, though Somali employees say some of the top international staff members make 10 times that much. United Nations officials declined to provide salary figures.

The Somali government has promised not to change the operation and to keep the Nairobi flight control center open. It merely wants the ownership of the airspace transferred back to Somalia; that way, Somali officials say, they will better manage the money generated by the flyover fees and make more improvements to Somalia’s airports.

“The right of Somalia to take over the responsibility” of its airspace “is undeniable in the light of international law,” read a letter from the previous prime minister, Omar Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke, dated last May.

Gesturing to the crumbling terminal building at Mogadishu International, where passengers wait for crews in grubby overalls to wheel up a decidedly shaky set of steps, Captain Mohamoud said: “You know, these people are collecting our money, using our money, and look at us. We just want to be like any other country and have a real airport.”

www.nytimes.com

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar