Somalia key to safer seas

Experts: Land stability beats military might against piracy

By Geoff Ziezulewicz, Stars and Stripes

European edition, Monday, February 15, 2010

Elizabeth Allen/Courtesy of the U.S. Navy.

A Coast Guard team, with members of the visit, board, search and seizure team stationed aboard the USS Farragut, investigate a Somali skiff in the Gulf of Aden on Feb. 2. Attacks on commercial ships in the Gulf have increased significantly, from 13 in 2007 to 116 in 2009.

RAF MILDENHALL, England — Solving the Somali pirate problem plaguing the Horn of Africa and the Gulf of Aden seems like a no-brainer: The might of the world’s navies surely will prevail against criminals armed with AK-47s and riding in skiffs.

In fact, it isn’t so simple, experts say.

Because of the seemingly endless miles of open ocean that need to be patrolled, military limitations and the anarchy that has troubled Somalia for nearly 20 years, piracy will not be going away any time soon. And it won’t be stopped by the myriad military task forces and assorted navies now sailing those vital commercial shipping corridors.

“You cannot hope to tackle piracy in any kind of serious way without any kind of change on the ground in Somalia,” said Roger Middleton, a maritime analyst with London’s Chatham House think tank. “This is not started on the ocean, and it’s not a problem that can be solved on the ocean.”

Pirate attacks off Somalia rose from 19 in 2008 to 80 in 2009, according to the International Maritime Bureau. The Gulf of Aden logged just 13 attacks in 2007, but reported 116 in 2009.

The number of attempted hijackings is likely greater, but ship owners are reluctant to report the incidents out of concern that it will lead to an increase in their insurance premiums and result in lengthy, costly post-attack investigations, according to testimony last year by RAND Corp.’s Peter Chalk to the House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee.

In response to the increased threat, the U.S. in early 2009 announced the creation of Combined Task Force 151, a Bahrain-based coalition. On average, the task force has 24 ships conducting counterpiracy operations in the Gulf of Aden, Indian Ocean and Arabian and Red seas at any given time, said British Royal Navy Lt. Cmdr. Francesca Woodman.

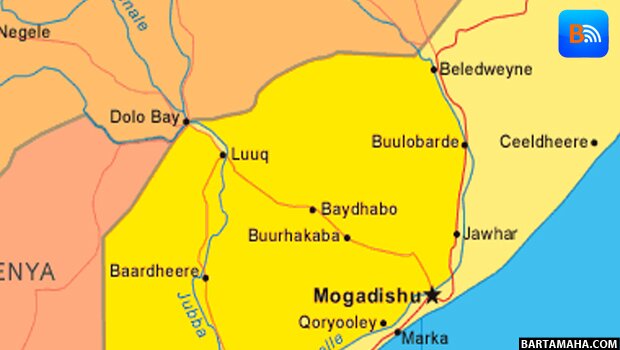

But having more materiel than the opponent does not guarantee victory. A military presence on the waters will not end the threat, because these navies can’t be everywhere at once, analysts say. Those 24 ships are patrolling an area of 1.1 million square miles, roughly four times the size of Texas.

Commercial ships transiting the Gulf — many carrying oil — do not carry armed guards for fear of setting the oil ablaze.

The pirates sit in small skiffs in the Gulf and attack any vulnerable ship. They strafe the ship’s bridge with AK-47s to warn the vessel to stop. The pirates climb aboard using ladders and grappling hooks and secure the vessel, working from the bridge down through the ship.

Piracy is a threat because it bites into global maritime commerce and the “enormous volume” of commercial freight moved by sea, Chalk said in his 2009 testimony. Anywhere between $1 billion and $16 billion is lost to piracy each year. Somali pirates are projected to have netted “at least” $20 million in ransoms in 2008, Chalk said, including $3 million for the release of one Saudi-registered vessel.

“For many gangs, the prospect of windfall profits such as these far outweighs any attendant risk of being caught or otherwise confronted by naval or coast guard patrol boats,” Chalk said.

The sophistication of piracy has jumped markedly in recent years, especially in the waters off East Africa, Chalk said.

“Gangs now routinely hijack large ocean-going vessels and have exhibited a proven capacity to operate as far as 500 nautical miles from shore,” he said.

In October, for instance, pirates hijacked a Chinese vessel some 800 miles off Somalia’s coast.

Nevertheless, piracy simply isn’t at the top of the international community’s to-do list, despite the very visible effects, Middleton said.

“It’s nowhere near as high up the list of priorities as it would need to be,” he said.

Somali pirates have managed to stay apolitical and are largely a criminal enterprise, Middleton said. If they were to associate themselves overtly with the al-Shabaab Islamist group in Somalia or other militant organizations, they’d likely become a higher priority for the international community, especially as concerns mount over Somalia becoming a terrorist haven.

Piracy was born largely out of Somalia’s lawlessness. The country has been without a functioning government since Mohamed Siad Barre’s regime collapsed in 1991, ushering in anarchy and factional fighting that continue to this day.

There is a U.N.-backed government that controls a small portion of the country, but until Somalia’s security and governmental capacity is strengthened, piracy will continue to be a viable livelihood for some Somali men, said Jason Alderwick, a maritime analyst with London’s International Institute for Strategic Studies.

“The international contribution, whilst welcome, is currently not enough,” he said.

And until this void in regional governance is decisively filled, Chalk said, “the waters off the Horn of Africa/Arabian Peninsula will remain a highly attractive theater for armed maritime crime.”

Source Stars and Stripes.

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar