Piracy opened world’s eyes to war-torn Somalia

Recent pirate attacks in the Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden finally have turned the world’s attention on Somalia after years of the war-ravaged country being ignored, East African experts say.

Piracy is the unfortunate, albeit headline-grabbing, symptom of a much larger concern of a nation rocked by poverty and governmental instability.

While there are some short-term solutions to fighting piracy, a military offensive won’t resolve the issue, experts say.

“It’s not a military solution,” said Roger Middleton, a Horn of Africa expert with the Royal Institute of International Affairs Chatham House think tank in London.

“There are things a military can do to make it safer, harder for pirates, but that’s not the solution.”

The first thing that needs to happen is changing the approach to Somalia’s problems, he said.

“When Somalia hasn’t been ignored, which, in fact, it has mostly been ignored … there were attempts to contain Somalia without attempting to help it,” Middleton said in a telephone interview. “That approach has failed.”

There have been nearly 20 peace processes in Somalia, but none has been successful, he said.

“There has never been high-level engagement by the world, such as there have been in places like Sudan,” Middleton said.

But the swell of successful pirate attacks now is topping international agendas.

“The problem of piracy has opened the eyes of those who have forgotten Somalia,” Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah, a U.N. special representative for Somalia, said during an international conference last month in Brussels.

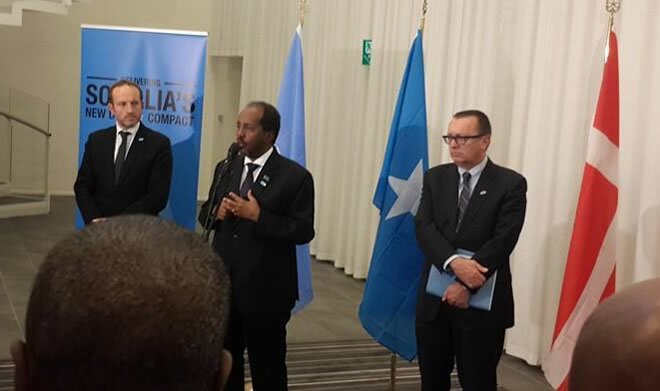

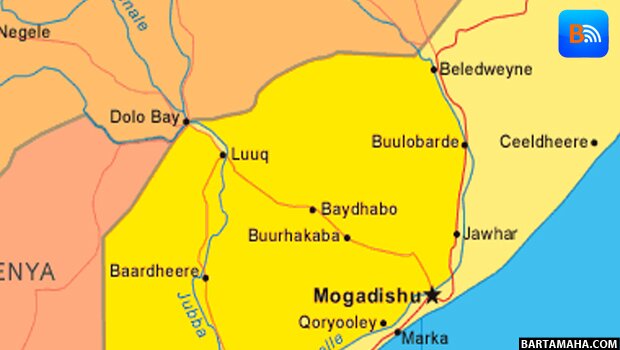

World leaders pledged $213 million during an April 23 fundraiser co-sponsored by the United Nations and European Union, an opening step to aid the East African nation that is slightly smaller than Texas.

The money will go toward security to fund African Union forces in Somalia and the development and training of a Somali security force.

Somalia hasn’t had a long-term functioning federal government since dictator Siad Barre died in 1991.

After 15 years of warlords and militias fighting a brutal chess match for power, the stern Islamic Courts Union took control of the capital of Mogadishu in 2006.

Backing the government, currently led by President Sheikh Sharif Sheikh Ahmed, and funneling cash into the nation — to create jobs, rebuild infrastructure and stimulate growth — will go a long way toward quelling the piracy problem, experts said.

“There isn’t a short-term solution,” Middleton said.

“This will take years, possibly decades, to work itself out.”

However, there are some short-term options — even a few where military forces might play a vital role, said Peter Lehr, a lecturer in terrorism studies at the Center for the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence at the School of International Relations at University of St. Andrews in Scotland.

For example, strategically positioned, big-deck warships can serve as landing platforms for helicopters that can patrol the area, he said.

Satellites and drones also can be used to spot the so-called “motherships” that serve to replenish pirates who operate in smaller skiffs to board and hijack commercial vessels, Lehr suggested.

“That would be a quick fix, make a dent in the piracy by denying them their long reach,” he said.

A more “midterm” solution to help stem the problem would be to create a regional anti-piracy patrol, headed by nations such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Oman; similar to patrols to protect against legal fishing in Southeast Asia among countries such as Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and Thailand, Lehr said.

In the 1990s, those Southeast Asia nations pooled resources to patrol the Strait of Malacca. And though it proved successful at the time, it was too expensive to maintain, and they ended patrols after about six months, Lehr said.

A scaled-back effort, with fewer warships, started again a few years ago, with nations relying more on technology, such as drones and radar, to accomplish the same result.

The reason behind having patrols spearheaded by regional countries is a matter of politics and strategy, Lehr said.

“If it is internationally led, or U.S.-led, it can be misconstrued as ‘forced upon them’ and yet another anti-Islamic effort,” he said.

“But if it is regional, … it steals al-Qaida and [extremists’] thunder.

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar