OUR STORIES, OUR LIVES

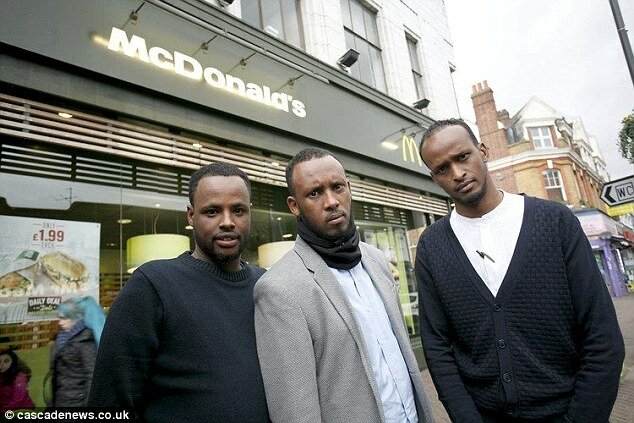

From left, Abdikadir Omar, Faisal Farah, Abdi Keynaan and Tooxoow Hirabe play dominoes as they and other cabdrivers await customers on a recent Sunday outside Omaha's Eppley Airfield. On slow days, the wait can be three or four hours for the next fare, Keynaan said.

The first cabdriver in line sleeps on the sidewalk behind the tall wood fence as airport-bound cars stream by and planes roar into the sky.

Another driver catnaps in his taxi, his flannel shirt stretched across the window to block the late afternoon sun.

A third sits on a pillow, staring at his cell phone screen where a sheik reads from the Koran. A fourth calls home, chattering in a language that sounds older than time.

The drivers have waited hours with few customers. About 20 others trade news, play dominoes, troll the Web from laptops or rib each other. A couple even do a friendly riff on race.

Bill, the White Guy, counts the other white drivers he knows are out there.

“There’s two or three,†just not today, says the 62-year-old in Birkenstocks, laughing. “We’re going to take it back over,†he declares to Mohamed, the Diplomat, who meets Bill’s laugh with twinkling eyes and raises him a good-natured jab:

“We have to give him minority rights,†Mohamed deadpans.

Thus another Sunday plays out in the taxi queue south of the main terminal at Eppley Airfield. The line and the cabbies stuck in it might as well be invisible to those who drive by to drop off relatives.

The cabbies are men digging into car trunks for bottled water to splash on their faces, feet and hands before prayer. Men in chinos and collared shirts kicking a soccer ball on an empty patch of concrete near the long-term parking. Men laughing, playing music. Men worried about families, about wives who are either stuck back in Africa or here minding the kids or working at meatpacking plants. Men wishing for shade and running water in this no-man’s land of fences and warning signs.

Men wondering when the green light will flash on, moving the line of taxis forward.

If foreign-born cabbies with thick accents are one measure of a city’s entree to the big time, then Omaha, with its growing number of Somali cabdrivers, can say it has arrived. Happy Cab counts nearly 40 Somalis among its 157-driver ranks, a corps that also includes drivers from places like Sudan, Ethiopia, Benin, Togo, Kenya, Nigeria, Liberia.

The Somalis have landed in Omaha because of friends and friends of friends and the city’s reputation among the Somali diaspora for jobs, schools and services. Mohamed Rage, a Somali community organizer, estimates the Somali population in Omaha to be 550.

It’s a fraction of the Sudanese, who started coming years earlier for the same reasons. And it’s about 10 percent of what Rage says is Nebraska’s 4,500-strong Somali population, which is spread among the state’s meatpacking towns: Grand Island, South Sioux City, Lexington, Columbus.

It’s difficult to get an accurate count of Somalis here. The last Census a decade ago occurred before a big wave of immigration — and the Census has historically undercounted refugees and minorities. A separate federal count only includes those who came here straight from Somalia, not from other states where they might first land. One local Somali advocate estimates Omaha’s number as much bigger — around 2,000. Rage last year did his own informal wcounts of Somali-heavy neighborhoods in Omaha, checked those over with several Somali merchants and stands by his number.

However many there are, those driving cabs in Omaha are learning that the city is no cabdriver’s gold mine — not when a significant portion of the city’s residents wouldn’t dream of putting Grandma or Aunt Sue or college friend Joe in a cab to the airport. Personal airport drop-off and pickup is a point of pride here, symbolic of the city’s larger disregard for public transportation.

ALYSSA SCHUKAR/THE WORLD-HERALD From left, Abdikafi Kheyre, Ali Abdi, Fathi Nor and Abdikadir Omar break their daylong fast during Ramadan while waiting for fares Aug. 23 outside Eppley Airfield. Omar brought food from home that his wife had prepared for him and for other drivers who have no family here.

Commutes are short enough, streets are open enough, parking is not the chore downtown that it is in other major cities.

Happy Cab knows this. That’s why the predominant cab company in Omaha (Happy owns Yellow and Checker and runs Cornhusker) has diversified. It contracts with school districts to pick up children, with organizations that serve the developmentally disabled and with a trucking firm whose drivers sometimes switch out trucks and need rides.

This helped Happy weather a recession that has hit bigger cab cities harder. John Davis, director of operations for Happy Cab, figures his drivers have seen a 10 to 15 percent drop in business — less than the 25 percent drop he has heard of elsewhere.

But though demand is down, supply is up. As more Somalis come to Omaha, more work as cabbies with flexible — albeit long —hours. The job also offers wheels for personal use. Drivers have to lease those wheels — usually for $400 a week — and pay for gas. Cab companies pay for maintenance.

They can pay an extra $10 a week for dispatch service that gives them customers in an assigned area, which some of the airport drivers choose to buy. Others prefer to hustle for themselves. In all, Davis estimates the company completes 1,100 trips a day.

What also draws Somalis to the job — especially those in the airport queue — is being in the company of others who speak Somali, worship Allah and provide a vital link to news about Back Home, even if Back Home for most of them is not Somalia but the neighboring African countries where they started to flee when Somalia’s brutal civil war began in 1991.

The queue may crawl, the conditions may not be four star, but there is an esprit de corps.

That’s something Davis admires. The majority of Somali drivers, he says, are family men whose obligations to each other appear to extend beyond kinship. They respect their elders, they share what they have.

We hardly even know our own neighbors, Davis says about Americans.

In the examples of the Diplomat and the One Who Made It, the American dream seems possible.

First, the Diplomat. Mohamed Rage is a veteran cabby (six years in Omaha; 11 years in the D.C. area) and a veteran immigrant (came to the U.S. in 1980). He has a college degree and runs a Somali community and advocacy organization. He is a fixer, a translator, a guide for both Somalis and Americans.

He is conversant in Somali, the ancient tongue of the country shaped like a figure 7 in the Horn of Africa. It is a place that has known triumph: centuries as a commerce center, a military power that successfully blocked several British attempts at invasion until finally losing, a country that valued literacy. Somalia also has also known disaster. Clashing clans. Unending civil war. Piracy, lawlessness and famine.

Mohamed is conversant in English and savvy in bridging not only language but culture.

Yes, he acknowledges, Omaha is not a cab city . . .

“But we are trying to convert it! We are just making Omaha to become a cab city!â€

And, yes, the cabdrivers sometimes sit for a long time.

“But this (job) allows you to wake up every morning and show your children you’re going to work!â€

There’s an example of that (call him Exhibit A): the One Who Made It.

Cali Hadafow doesn’t wait in the airport line for fares. He did that from 2001 to 2004 when, as he recalls, only 10 Somalis were driving cabs. The lines were shorter then, and people were more flush.

In 2005, he opened a midtown grocery store specializing in African, Middle Eastern, Indian and European foods.

This former history teacher — he graduated from Somalia National University in Mogadishu — fled when the war started and has not returned: “You are likely to be killed there.â€

Omaha, by contrast, “is a good place to be, a good place to raise a child,†he says.

The grocery store did well enough for Hadafow to open a restaurant earlier this year near Turner Boulevard and Farnam Street. Safari Restaurant might as well be in Mogadishu for how difficult it is to reach during rush hour because of the Midtown Crossing construction at Turner Park.

Yet it could be prime real estate once apartments, condos and a hotel fill up and moviegoers want to sample the halal fare (which meets Muslim rules) Hadafow makes with help from his wife and children, ages 18, 16, 14, 11 and 10.

Safari is a landing spot for tired, hungry cabbies, especially now during Ramadan, the month of fasting in Islam.

But back in the taxi queue outside Eppley, nightfall and the hours in which Muslims can break fast are hours away.

The line, dead still at 4 p.m., has begun to come to life an hour later.

The green light, which signals when cabbies are needed at the terminal, is flashing intermittently.

The Pharmacist, who had pulled his cab into the line at 8 a.m., has by 5:30 p.m. earned fares from two customers: one going downtown for $10 and another to 72nd Street for twice that amount.

Now Fathi Nor’s white cab sits again at the front of the line. It would soon be his turn again. The 30-year-old would rather study pharmacy and be doing that work, as he was before coming to the U.S. in 2000.

But English is still very hard. And college standards are different here.

He’s been driving in Omaha for three years.

As the light flashed green, Nor was kneeling on his prayer rug facing northeast on the sliver of sidewalk where devout Muslims take turns at prayer five times a day.

“LIIIIGHT!†yell the cabbies. Horns honk.

But the Pharmacist doesn’t move. The driver who was second in line pulls ahead and zooms toward the airport.

Nor finishes, slips his bare feet back into brown Top-Siders and hops into his cab.

The light flashes again.

And he is off to meet a customer.

__________

Source: Omaha World Herald — By Erin Grace

Photos by Alyssa Schukar

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar