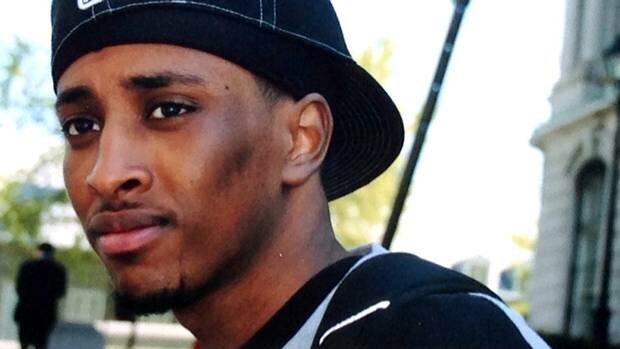

Music lover escaped war-torn Somalia to defy the odds in Vancouver

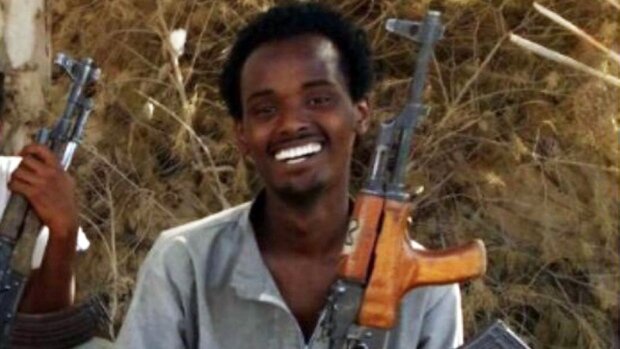

METRO VANCOUVER — His musical tastes were eclectic: He loved the sensual melodies of American R&B, the rhythm of reggae, the upbeat tempo of bhangra. He incorporated his wide-ranging tastes into songs he wrote himself, and into the music he taught to several bands whose songs he directed.

But living in Mogadishu, Somalia, Gaandi Muhamed Sufi’s love for music was a dangerous one.

Devoid of an effective central government since the fall of President Mohamed Siad Barre in 1991, the war-torn nation has become a casualty of the conflict between rival warlords, the country plagued by human-rights violations, famine and disease.

In April, Islamist militants Hizbul Islam, one of the country’s two main insurgent forces, issued an explicit warning to Somali radio stations demanding they stop playing music, which they deemed “un-Islamic.”

“The Islamist [insurgents], they don’t like to hear someone, he makes songs, he makes films,” Sufi said in broken English. “Then I [was] scared myself. I run from Somalia…. If you live in Somalia now, you can’t sleep well. Always, you’re scared. Next to village, two groups fighting.”

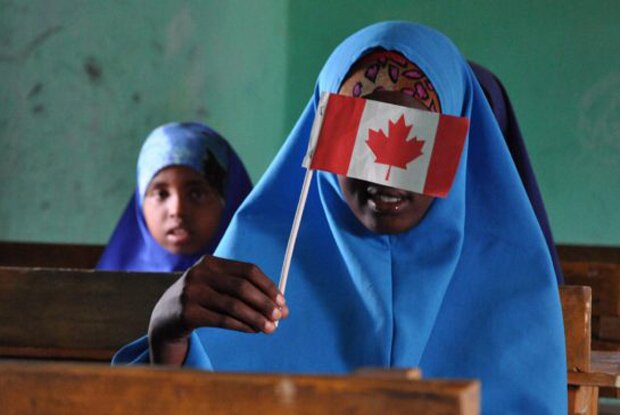

With the support of his wife and five children, Sufi set off to seek a better life for himself and his family. In January 2007, Sufi took a ship to Istanbul, Turkey, contacted the United Nations Refugee Agency and asked for help. He said the agency connected him with the Canadian embassy, which helped bring him to Vancouver in July.

Between January 2005 and December 2009, the federal government, through the Department of Citizenship and Immigration Canada, brought 4,026 people from 46 countries to B.C., according to a new report by the Immigrant Services Society of B.C. Of those, 251 were from Somalia.

The majority of the Somali government-assisted refugees stayed in Metro Vancouver, while about 25 per cent ended up settling in Edmonton, Alta., and Hamilton, Ont., the report stated. Of those who stayed in Metro Vancouver, 145 settled in Surrey, while 30 settled in Burnaby.

As part of Canada’s Resettlement Assistance program, refugees are eligible for up to one year of income support through Citizenship and Immigration Canada, at rates that mirror provincial welfare rates.

The vast majority require support their first year, then transition to provincial income assistance for reasons such as pre-existing medical conditions and differing levels of literacy, said Chris Friesen, director of settlement services at the Immigrant Services Society of B.C.

Sufi arrived in Vancouver on July 20 and for two weeks stayed at the ISS’s taxpayer-funded Welcome House in downtown Vancouver, the temporary accommodation provided to refugees to help with the transition.

He said he remembered joking with a Welcome House employee who was explaining crosswalk signals.

“She said, ‘When you see the man, you can go. When you see the hand, you have to stop.’ When I saw the hand, I made the hand,” he said, holding up his hand and laughing.

“She laughed and I said, ‘No, I kidding you.’ “

Sufi eventually settled into a one-storey home, which he now shares with four other tenants on Renfrew Street in East Vancouver.

His modest bedroom, for which he pays $425 per month, is littered with trinkets from his past and present: On his television set sits a small photo album filled with family snapshots; next to it is a stereo, on which he plays all the music he likes. Pinned to the lilac wall above the bed hangs a large Canadian flag – an item left behind by a previous tenant that Sufi found fitting to keep.

“I say, ‘I’m in Canada now.’ I keep it,” Sufi said, smiling.

On the wall behind his door hangs a Freshslice Pizza hat, part of the uniform he wears to work, eight to 10 hours a day, six days a week, making pizza dough to be delivered to individual restaurants. It’s a job he got less than two months after his arrival in Vancouver, defying the odds.

Sufi said he will never forget the night he was scheduled to start work.

“The SkyTrain, I didn’t get,” he recalled with a smile. “It was 12 midnight. Until [2 a.m.] I didn’t get. Also, I have no money in my pocket. So, two hours I run around Gilmour and Canada Way. I couldn’t see the police, because if I see them, I can say, ‘Please help me. I’ve lost my way.’ Then you know the bus station? I sleep there until morning.”

Fortunately, his employer was sympathetic and gave him another shot.

A few months in, Sufi told the citizenship department he no longer needed financial assistance.

“I got the job, I started. I said, ‘Now, enough. I don’t need your money,’ ” he said. “They send me e-mail, they say, ‘Thank you. We never see like you.’ “

Sufi said he would one day like to visit Toronto, where there is a large Somali population, and perhaps pursue a career in music again. But for now, his immediate goals are to get a second job and save up enough money to help bring his family to Canada.

“When your family, your wife and your children, are not with you, you worry,” he said quietly. “When they come, my heart and my brain and my mind, everything will be all right.”

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar