Legal pitfalls in pursuing Al-Shabaab across border

Even in declaring war, the Kibaki administration has a dysfunctional trait unique in the community of nations.

Our men and women in uniform are sent to Somalia on a short notice and the commander-in-chief remains mum. He neither informs Kenyans, much less justify, the mission.

We hear the declaration of the war from the Minister in charge of police and administration police!

The legal basis upon which Kenya has invaded Somalia has not been elucidated by either the Foreign Affairs ministry or the Attorney-General. Kenyans, out of a nationalistic duty, rally behind our soldiers.

Still, the government needs to explain to Kenyans the legal justification and security rationalisation behind the invasion of Somalia. War has a huge propaganda component and the government must realise that.

In an era when both the International Criminal Court and the International Court of Justice can assume jurisdiction in relation to the acts of governments, Kenya must act very cautiously and engage the international community urgently.

The Minister for Internal Security has cited Article 51 of the United Nations Charter as the legal justification for the war.

A closer scrutiny shows that no such justification exits both under customary international law and even upon a liberal interpretation of Article 51.

The conflicting signals from Somalia further complicate our position. Only an unequivocal statement form Somalia requesting the assistance of Kenya in eradicating the Al-Shabaab menace will do.

It must be remembered that when Ethiopian forces crushed the Union of Islamic Courts in Somalia, the same was upon an express request by Somalia.

If no formal request is forthcoming from Somalia, Kenya can try to hinge its decisions on two concepts of international law. The first is the right to self- defence.

The second is the right of hot pursuit in international law. In both cases, Kenya must set a specific reasonable time frame for its incursion.

An open ended intrusion into Somalia, no matter how noble the pursuit, will be a clear violation of international law.

It will also establish both state and individual responsibilities for specific Kenyan officials in the chain of command.

One of the difficulties facing Kenya is that self-defence under Article 51 of the UN Charter is always subject to a supervisory control by the Security Council.

Kenya has no such authorisation. The second challenge is the judgment of the ICJ in the Nicaragua versus America case.

In this case the court, in dismissing America’s assertion that in laying mines in waters near the Nicaraguan coast, America was acting in collective self-defence with El Salvador, the court ruled that the acts that trigger the right to self-defence must be grave enough to amount to an armed attack.

Third, self-defence is limited to the right to use force to repel an attack in progress, to prevent future enemy attack following an initial attack, or reverse the consequences of an enemy attack that intends to end an occupation.

Kenya has a better case in basing its actions on the right of hot pursuit in international law.

This right is often allowed on the high seas. But this doctrine has been used quite often by countries like Israel and Turkey to justify limited incursions into the territory of a neighbouring state.

Kenya has a good claim to state that it is pursuing Al- Shabaab elements that crossed and kidnapped people in Kenya. For Kenya to persuade the rest of the world, a specific time frame must be set.

The strategic national interest of Kenya should ultimately inform and guide the mission. We must avoid an open ended and expensive adventure in Somalia.

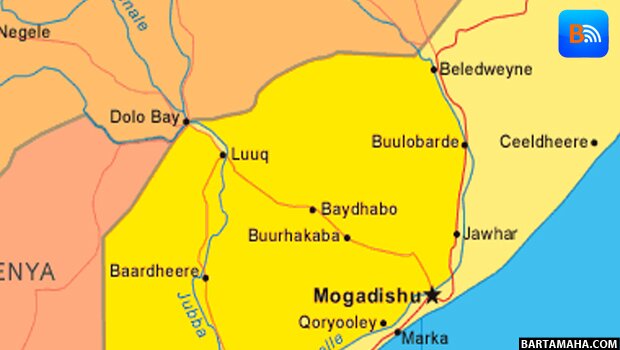

We must avoid the creation of semi-autonomous entities like Jubaland or Azania. President Kibaki must share with us his exit strategy. How long will our soldiers remain in Somalia?

Ahmednasir Abdullahi is the publisher, Nairobi Law Monthly [email protected]

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar