Lawyers vs. Pirates

As if catching pirates weren’t hard enough, now we have to figure out what to do with them. And no, they can’t all just walk the plank.

Somali pirates have not exactly had a banner month. Last week, 11 pirates charged with firing on two U.S. Navy warships were hauled into a U.S. federal court in Norfolk, Virginia, where they could be sentenced to life imprisonment. Other Navies have also captured their share of buccaneers, including the French, who nabbed six, and the Spanish, who took another eight. Dozens of ships from various countries are currently patrolling the Gulf of Aden and parts of the Indian Ocean, looking to round up marauders.

Unfortunately though, better (albeit still very imperfect) enforcement is leading to its own headaches. Yes, it looks great for the United States and other countries to be tossing more and more pirates into the brig. But the problem of what to do when the pirates land there is turning every pirate-hunter into a scholar of international law, and may make all the heightened security look a bit useless.

At least in theory, there should be no legal ambiguity about putting pirates behind bars. Pirates, after all, have been regarded from time immemorial by the Law of Nations (jus gentium) as enemies of the entire human race, subject to the universal jurisdiction of any state that could get its hands on them. That spirit was codified in the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, which has been ratified by 160 countries (albeit not by the United States).

And the U.N. Security Council has worked to shore up the international legal framework even further. Two years ago, a resolution authorized states cooperating with Somalia’s largely moribund Transitional Federal Government to “enter the territorial waters of Somalia for the purpose of repressing acts of piracy and armed robbery at sea, in a manner consistent with such action permitted on the high seas with respect to piracy.”

But the devil is in the details. Many countries either lack the right legal code to dub piracy a criminal offense or the procedural provisions to do so. Even in countries with the right laws are on the books, conducting successful prosecutions can be extremely difficult. There are few lawyers skilled in the minutiae of piracy law, gathering evidence at sea is logistically very hard, and transporting witnesses from the Gulf of Aden is no small task. The United States is about to learn this lesson now with the trial of Abduwali Abdukhadir Muse, the sole survivor of the four-man pirate gang who attacked the MV Maersk Alabama in April 2009 and held Captain Richard Phillips hostage for nearly four days. In fact, to avoid a complicated trial, prosecutors may allow him plead guilty to a lesser offense.

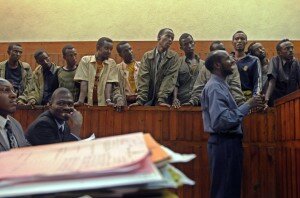

Up until now, Kenya and the Seychelles have taken the majority of the caught pirates, thanks to memoranda of understanding they signed with the anti-piracy fleet. But over the last year, they have simply reached their limit. Their judicial systems are overburdened as it is. It’s not just a matter of funding, although that has been one hold up: The two countries simply don’t have enough local prosecutors and defense counsels capable of handling these complicated cases. And in the case of Kenya, the country’s own restive ethnic Somali and Muslim populations were growing antagonized by a seemingly endless parade of Muslim Somali prisoners captured by Western warships.

All the legal hoopla meant that very few pirates actually made it to court. According to one U.S. tally, some 706 individual pirates were encountered by naval vessels of the ad hoc counter-piracy coalition between August 2008 and December 2009. Eleven of these were killed resisting arrest and another 269 turned over for prosecution. Just 46 have been convicted so far and 23 acquitted. All together, that means that nearly 60 percent of the pirates encountered were simply released.

This week, the U.N. Security Council stepped in once again, unanimously adopting a Russian-sponsored resolution on the matter. The resolution requires the secretary-general to report back with options for prosecuting and imprisoning pirates, including the creation of special international piracy courts. If countries can’t or won’t try the pirates, then darn it, the U.N. will.

The United Nations proposal is well-meant, but it may never come to fruition — or if it does, it may be too late for the current crop of pirate-hunters to take advantage. The secretary-general’s recommendations are still three months away and their implementation is still further in the horizon. And if past internationalized criminal proceedings are any indication, the courts will take several years to actually set up — and that’s assuming that the political will and money can be found to do so. (The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, for example, cost $376 million just for 2008 and 2009.)

Meanwhile, despite all the international community’s efforts, the pirates are still plying their trade. Just last week, they pulled one of their most daring heists to date, sailing some 1,200 nautical miles from the Somali coast — right past the naval task forces led by the United States, the European Union, and NATO, as well as the independently commanded Chinese, Russian, and Indian flotillas — to seize three Thai fishing boats along with their 77 crew members. In terms of distance offshore and sheer number of hostages taken, the raid broke all previous records.

For the buccaneers, the equation still works out in their favor: exceptionally high rewards — in January, a Greek-flagged tanker, the MV Maran Centaurus, was ransomed for a record $7 million — traded for an extremely low probability of ever being prosecuted, much less convicted and sentenced. No wonder the pirates just keep on coming.

———

Source:-foreignpolicy

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar