Kenyan Motives in Somalia Predate Recent Abductions

NAIROBI, Kenya — The Kenyan government revealed on Wednesday that its extensive military foray into Somalia this month to battle Islamist militants was not simply a response to a wave of recent kidnappings, as previously claimed, but was actually planned far in advance, part of a covert strategy to penetrate Somalia and keep the violence in one of Africa’s most anarchic countries from spilling into one of Africa’s most stable.

NAIROBI, Kenya — The Kenyan government revealed on Wednesday that its extensive military foray into Somalia this month to battle Islamist militants was not simply a response to a wave of recent kidnappings, as previously claimed, but was actually planned far in advance, part of a covert strategy to penetrate Somalia and keep the violence in one of Africa’s most anarchic countries from spilling into one of Africa’s most stable.

For several years, the American-backed Kenyan military has been secretly arming and training clan-based militias inside Somalia to safeguard Kenya’s borders and economic interests, especially a huge port to be built just 60 miles south of Somalia.

But now many diplomats, analysts and Kenyans fear that the country, by essentially invading southern Somalia, has bitten off far more than it can chew, opening itself up to terrorist reprisals and impeding the stressed relief efforts to save hundreds of thousands of starving Somalis.

Somalia has been a thorn in Kenya’s side ever since Kenya became independent in 1963. Somalia has become synonymous with famine, war and anarchy, while Kenya has become one of America’s closest African allies, a bastion of stability and a favorite of tourists worldwide.

Kenyan officials said it was becoming impossible to coexist with a failed state next door. They consider the Shabab, a ruthless militant group that controls much of southern Somalia, a “clear and present danger,” responsible for piracy, militant attacks and cross-border raids.

When Kenya sent troops storming across Somalia’s border on Oct. 16, government officials initially said that they were chasing kidnappers who had recently abducted four Westerners inside Kenya, two from beachside bungalows, and that Kenya had to defend its tourism industry.

But on Wednesday, Alfred Mutua, the Kenyan government’s chief spokesman, revised this rationale, saying the kidnappings were more of a “good launchpad.”

“An operation of this magnitude is not planned in a week,” Mr. Mutua said. “It’s been in the pipeline for a while.”

Many analysts wonder how Kenya will be able to stabilize Somalia when the United Nations, the United States, Ethiopia and the African Union have all intervened before, with little success. They argue that the Kenyan operation seems uncoordinated and poorly planned, with hundreds of troops bogged down in the mud during seasonal rains.

Kenyan military officials also publicly said the United States and France were helping them, but both countries quickly distanced themselves from the operation, insisting that they were not taking part in the combat.

“The invasion was a serious miscalculation, and the Kenyan economy is going to suffer badly,” said David M. Anderson, a Kenya specialist at Oxford.

The Shabab, who have pledged allegiance to Al Qaeda, have killed hundreds in suicide attacks in Somalia and are now vowing to punish Kenya, much as they struck Uganda last year for sending peacekeepers.

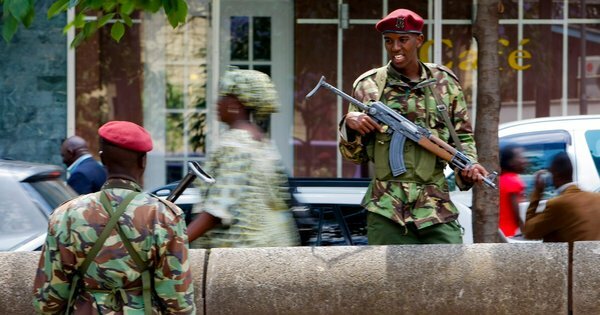

There have already been two grenade attacks in Nairobi, which Kenyan officials said were the work of Shabab members, and this usually laid-back capital city has shifted into war mode. Security guards peer into purses at supermarkets, shopping centers are deserted because many Kenyans are now scared to congregate in public, and the American government has warned of “an imminent threat of terrorist attacks” at malls and nightclubs.

Despite their close relationship with Kenyan security services, which receive millions of dollars in American aid each year, American officials said they had been caught off guard by the incursion.

“The United States did not encourage the Kenyan government to act, nor did Kenya seek our views,” said Katya Thomas, a spokeswoman at the American Embassy in Nairobi. “We note that Kenya has a right to defend itself.”

Pentagon officials are now watching cautiously. “This is not something that’s coordinated with us at all, so it’s not something we have much knowledge about,” a senior Pentagon official. “We want to see how this develops.”

Pentagon officials said the immediate impact of dispersing Shabab fighters was good. But without knowing much about the overall Kenyan strategy or long-term plan, they are a bit wary.

“It’s difficult to discern what’s the next step,” the official said.

Kenyan officials say the next step is marching to Kismayu, a port town controlled by the Shabab, who derive tens of millions of dollars a year in taxes from it.

But Lazarus Sumbeiywo, a former leader of Kenya’s army, said the Kenyans were erring tactically. “It should have been surgical strikes,” Mr. Sumbeiywo said, arguing for small teams of special forces to hunt down militants and eliminate them quietly.

In 1990, before he became chief of staff, Mr. Sumbeiywo said, he ran special operations to kill Somali gunmen who had infiltrated Kenya. He said that his men had worked in small units and that Kenya had been bedeviled by Somalia for decades. “It was like that all the way from the beginning,” he said, describing how Kenyan forces fought Somali militants in the 1960s and 1970s, losing hundreds of men.

Kenya has tried to use proxy militias in Somalia to push out the Shabab and create a buffer zone stretching to Kismayu. But the militias have been struggling, and Kenyan officials said their plans for a major port in Lamu, near Somalia’s border, were imperiled by the instability pouring out of southern Somalia.

“This isn’t about tourism,” said a senior Kenyan official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “This is about our long-term development plan. Kenya cannot achieve economically what it wants with the situation the way it is in Somalia, especially Kismayu.”

“Just imagine you’re trying to swim,” he added. “If someone is holding your leg and your arm, how far can you swim?”

Somali officials, despite being enemies of the Shabab, have been furious about the Kenyan incursion. Somalia’s president, Sheik Sharif Sheik Ahmed, called it an “inappropriate” encroachment on Somali sovereignty

The dispute has left Western diplomats to mediate between the two sides, but Mr. Mutua said that “a lot has been lost in translation” and that the Kenyans and the Somalis were still close.

Still, aid organizations are deeply concerned that the military operations will affect efforts to reach starving people in Somalia’s famine-stricken interior. The United Nations has said that tens of thousands of Somalis have died and that 750,000 could starve to death. The Shabab control many of the hardest-hit areas, and have blocked most Western aid groups from entering.

“Some of the drought-affected people who arrived from other parts of the country are now facing multiple displacements in the wake of the military activities,” a United Nations report said Wednesday. “Movement of humanitarian personnel and supplies are also likely to be restricted, subsequently affecting the timely delivery of assistance.”

___

NYTimes

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar