In Mogadishu, an enemy retreats but fear remains

For the first time in three years, al-Shabab militants no longer rule Mogadishu. But the African Union soldiers stationed in the city are still nervous.

For the first time in three years, al-Shabab militants no longer rule Mogadishu. But the African Union soldiers stationed in the city are still nervous.

On a desolate stretch of Bakara market, which al-Shabab used as a base, the soldiers walked passed houses pocked with bullet holes and shuttered shops during a recent visit. Young men of fighting age stared from rooftops.

“How do you tell who is the enemy?” said Maj. Paddy Akunda, spokesman for theAfrican Union force, gazing up suspiciously. “It’s difficult to know who is wearing a suicide vest.”

Al-Shabab suddenly retreated from most of the capital a month ago, leaving the city amid an uneasy calm. African Union and Somali government forces can now venture into the market, where the al-Qaeda-linked militia taxed merchants to fund its conflict.

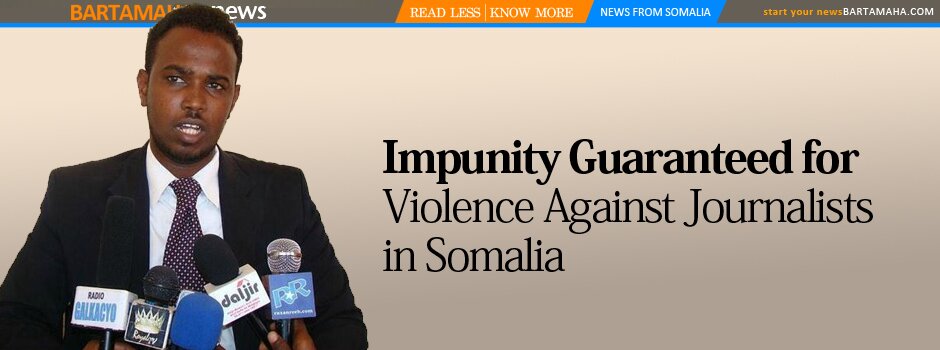

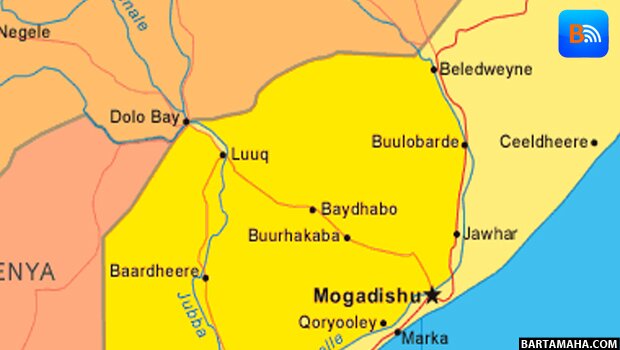

But hardly anyone is declaring victory over the militia. Al-Shabab still controls large swaths of territory and has vowed to retake the city, and many Somalis fear their country’s relentless civil war has entered a new phase in which an urban conflict with demarcated frontlines has turned into one with none, fueled by terrorist attacks by Shabab sympathizers who easily blend into the population.

The week Akunda’s troops visited Bakara market, there were five attempted car bombs or grenade attacks, African Union commanders said.

“The frontlines are no longer visible in Mogadishu,” Akunda said. “It’s more complicated now.”

The latest chapter in Somalia’s 20-year civil war comes as famine — the worst here in a generation — has already killed tens of thousands. Mogadishu is now filled with dozens of settlements of displaced people and long food lines, and the city’s hospitals are overwhelmed by starving children in desperate need of medical care.

During the past three years, al-Shabab grew strong enough to strike targets close to the seat of Somali’s government, paralyzing it. But why the Islamist militia, which once controlled 90 percent of the city, left seemingly overnight remains unclear. Some blame internal divisions; others say the African Union forces, trained by Western military trainers paid by the United States, pushed the it out with multiple offensives this year. And since the uprisings in the Middle East, less funding from Arab sympathizers was flowing into al-Shabab’s coffers, analysts say.

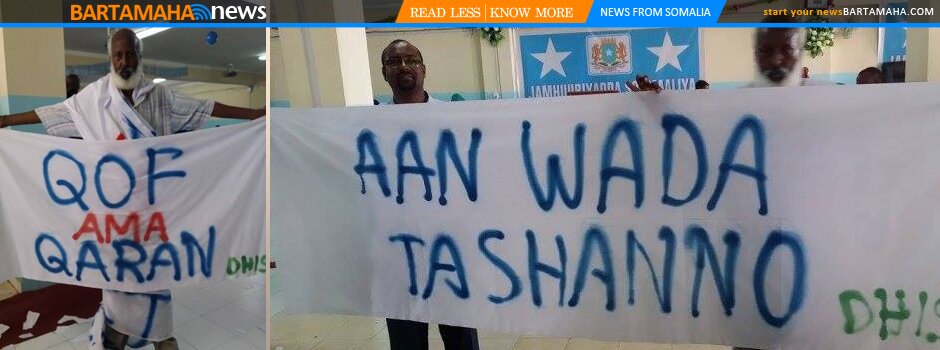

Whatever the reason, African Union officials and their international backers are hopeful Somalia’s weak transitional government can take advantage of the power vacuum. Under pressure from international donors, Somalia’s political and clan leaders agreed earlier this month to “a road map” to write a new constitution, reform parliament and take other steps toward building an effective government.

“Al-Shabab has served as a catalyst,” said Christian Manahl, the U.N. deputy special representative for Somalia. “It has helped bring together a number of parties and clans who have been fighting each other bitterly for years.”

The militia’s decision to ban international aid from entering southern Somalia, the famine’s epicenter, has also “delivered a blow to the militia’s credibility” among ordinary Somalis, he said. Fighters have stopped people from fleeing their areas, often at gunpoint, calling the U.N. declaration of famine exaggerated.

READ MORE

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar