In Hunt for Funds, Somalia Found Trouble

War-Torn Nation Enlisted U.S. Law Firm to Recover Overseas Assets, but Corruption Allegations, Resignations Followed

When Somalia’s government wanted to rebuild the country’s war-shattered economy in 2009, it hired lawyers to recover what it believed was more than $100 million of government funds frozen by foreign countries during two decades of civil conflict.

Things didn’t go according to plan. Over the past five years, the drive to reclaim the missing money has spawned corruption allegations and led to the resignation of two central bank governors. The fragile Somali government is now tussling with American lawyers over the funds.

Ugandan soldiers patrolled in Mogadishu, Somalia, after an attack by suspected militants on Aug. 31. Reuters

So far, the recovery effort has yielded only about $12 million, has imperiled the country’s relations with Western donors, and exposed disarray in the Somali government. After decades of conflict, Somalia is constantly teetering on the edge of chaos. Additional strife could destabilize the fragile country and a region trying to unite to fight a rising terrorist threat.

Somalia needs foreign aid and military support to fight al Qaeda-aligned militants. The corruption allegations have diminished donors’ appetites for funding the government, said Ken Menkhaus, a Somalia scholar at Davidson College.

Somalia is “a sieve for revenue,” he said. “It’s a place where it’s very difficult for external donors to ensure that funds are properly spent.”

Follow the Money

Key dates in the Somalian government’s attempts to reclaim assets.

- 1991: As fighting breaks out in Somalia, foreign countries freeze Somali government assets held in their countries to make sure they aren’t seized by any of the warring clans.

- 2009: Somalia’s former central bank governor begins talks with U.S. law firm Shulman Rogers about helping the new government reclaim the assets.

- Feb. 17, 2010: Date of contract between former Somali central bank governor and Shulman Rogers for the asset recovery.

- July 12, 2013: United Nations monitoring group releases report accusing government officials of using central bank as a ‘slush fund.’ Also date of renegotiated contract, which is signed three days later.

- Aug. 30: The Somalia government releases a report from Shulman Rogers concluding that allegations of financial mismanagement at the central bank are ‘false and contrary to the overwhelming weight of evidence.’

- September: Mr. Omer resigns. Yusur Abrar is named central bank governor.

- Oct. 30: Ms. Abrar resigns, alleging she was pressured to take actions to sanction the contract that would ‘open the door to corruption.’

- July 14, 2014: The central bank’s new governor, Bashir Issa, cancels contract with Shulman Rogers.

- Aug. 12, 2014: Shulman Rogers lawyer Jeremy Schulman holds a news conference in Minneapolis, apparently on behalf of the Somali government, promising litigation against U.N. monitors.

Five years ago, few expressed qualms about a nascent Somali government trying to fund its recovery from a long civil war between warring clans. But no one knew exactly how much money was abroad. Somali officials estimated it exceeded $100 million, enough to fund the annual budget at the time.

To spearhead the effort, interim President Sharif Sheikh Ahmed enlisted a trusted ally, Ali Abdi Amalow, who had been central bank governor when fighting broke out in 1991. Mr. Amalow turned to American law firm Shulman Rogers Gandal Pordy & Ecker PA. Jacob Frenkel, a partner at Shulman Rogers, said the firm has expertise in international asset recovery. “This is not a bunch of street-corner lawyers,” he said. “This really is the kind of sophisticated work that we do.”

In 2010, the Somali government agreed to pay the firm $50,000 a month; a bonus of 3.5% on recovered funds; and all costs, according to a contract signed by Mr. Amalow and the law firm that was filed with U.S. regulators. Some Somali officials balked at the contract’s open-ended terms.

“It was a blank check,” said Bashir Issa, who headed the newly reopened central bank from 2006 to 2010 and was recently reappointed to the post.

Mr. Frenkel said the terms were justified because of the high costs of the complex investigation.

But when the firm asked foreign governments for the money, they met resistance. Some governments queried why the contract was signed by a presidential adviser rather than Somalia’s central bank governor, said a Western European diplomat. A presidential spokesman didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The diplomat said his government ignored the request, hoping it would go away.

Shulman Rogers didn’t go away. Mr. Frenkel said the firm made “reasonable progress” but that political bickering inside the Somali government slowed the investigation. Somali officials have said they didn’t impede the effort.

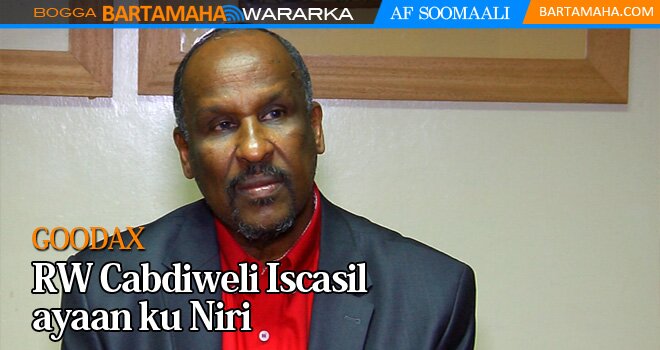

After two years of waiting and with fees piling up, Somali officials pushed to renegotiate the contract—this time with a signature from the central bank’s newly appointed governor, Abdusalam Omer.

But Mr. Omer was also being closely watched by the U.N. Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea, tasked with evaluating the massive international effort in the country. In a report issued July 12, 2013, they accused him of running the central bank as a “slush fund” for politicians. Mr. Omer resigned two months later amid the scandal. He denies the allegations and no criminal charges have been filed against him. He now lives in Nairobi and does consulting work.

Before he quit, Mr. Omer signed a new contract with Shulman Rogers that reduced the fees, but added a 6% charge to Somalia for “mutually agreed costs and expenses reasonably incurred by or on behalf of the central bank” beyond those already covered, according to a copy viewed by The Wall Street Journal. The 6% charge wasn’t further explained.

In July, the U.N. monitors wrote to the U.N. Security Council suggesting the 6% fee sought to conceal kickbacks to three presidential advisers. The Somali government has said there were no improper payments.

In an interview, Mr. Omer said the two sides agreed to set aside the 6% for extra possible expenses, such as hiring lawyers or other facilitators in countries where assets were found—or for travel by government officials to those countries. Mr. Omer said he renegotiated the contract to give the Somali government a better deal, which essentially waived $3 million in old fees.

Mr. Frenkel of Shulman Rogers calls U.N. allegations of kickbacks “untenable and ludicrous.” He denied the firm made any improper payments.

Soon after, Shulman Rogers recovered $12.3 million. Mr. Frenkel said he didn’t know exactly when the money was recovered or from which countries. The firm deposited $9.6 million in a Somali central bank account in Turkey, which is used to deposit foreign currency—including donor funds, said the current finance minister, Hussein Abdi Halane. Mr. Frenkel said he didn’t recall how the remaining $2.7 million was accounted for, and Shulman Rogers didn’t respond to follow-up questions.

A breakdown on Shulman Rogers letterhead—supplied to the Somali government and viewed by the Journal—shows almost $2 million of the remaining $2.7 million was used to pay fees and expenses. The rest was labeled as “6% expense set aside.” No further explanation was provided in a document labeled “fees and expenses calculation.” The law firm didn’t respond to an email asking it to verify the document.

The U.N. monitors allege the funds were funneled through companies that provided kickbacks to the president’s advisers.

The U.N. monitors weren’t the only ones to allege wrongdoing in the asset-recovery effort. Yusur Abrar, a former Citigroup C +2.09% executive the Somali president appointed to lead the central bank after Mr. Omer’s resignation, challenged the contract. But she only lasted seven weeks before leaving Somalia. In a resignation letter she sent from Dubai, Ms. Abrar said she had “been asked to sanction deals and transactions that would contradict my personal values and violate my fiduciary responsibility.” She said she had refused to approve the new contract because it “put the frozen assets at risk” and opened “the door to corruption.”

Ms. Abrar declined to elaborate on her resignation. The presidency said at the time that Ms. Abrar—who had lived mostly abroad—had been unprepared for the challenges in Somalia. A presidential spokesman didn’t respond to requests for additional comment.

About a week after Ms. Abrar’s departure, a group of senior Western diplomats flew into Mogadishu. They met President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, who took office in 2012, at the U.N.-protected airport and implored him to clean up his government, said a Western official briefed on the meeting. Otherwise, they warned, the billions of dollars of donor cash propping up Somalia would dry up. Mr. Mohamud promised more transparency and accountability, the official said. He pledged to publish all secret government contracts, create a financial oversight board with international representatives and seek World Bank advice in the asset-recovery effort. The finance minister confirmed these overhauls were being undertaken.

In July, Mr. Issa, the current central bank governor, canceled the contract with Shulman Rogers in a letter sent by air courier and viewed by the Journal.

In August, the firm’s lead on the Somalia effort— Jeremy Schulman —told reporters at a news conference that the firm had identified $33 million in assets so far. Most of that money was in the U.S., he said, without giving details on what was being done to obtain it. Another $50 million to $75 million was waiting in Europe, he said. He didn’t mention the canceled contract.

Finance Minister Halane and the bank chief, Mr. Issa, have since urged the president to distance himself from the American law firm.

In early September, Mr. Schulman traveled to Nairobi and met with President Mohamud at a hotel, said Awes Hagi, the president’s senior policy adviser. Mr. Hagi wasn’t at the meeting but said he was informed by those who were that Mr. Mohamud told Mr. Schulman that the contract was terminated. The president urged Mr. Schulman to discuss the contract with Somalia’s finance minister.

Meanwhile, Mr. Issa has accused Shulman Rogers of withholding a list of overseas assets the law firm’s probe yielded, and has threatened to sue for that information. “We know where some of the assets are,” he said. “A very few of them.”

Mr. Frenkel insists the Somali government is still a “valued client” and that the firm’s relationship with them “remains very amicable and open.”

Asked about the cancellation, he said, “It is certainly reasonable to believe that Shulman Rogers could be doing work for some ministries—including the office of the president—but not other ministries.” He declined to elaborate.

Asked about the accusations that the firm was withholding information about the assets discovered, Mr. Frenkel said the information may have gone to some parts of the government but not others, since not everyone in the government would be entitled to see the list, but declined to confirm either way.

“Merely because someone within the government asks the question that does not mean that person is entitled to the answer,” Mr. Frenkel said. He didn’t respond to questions about the threatened suit.

Source: Wall Street Journal

Write to Heidi Vogt at

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar