Hope and fear

They were four friends bound for Washington, D.C. to witness Obama’s inauguration. But around the same time they left Ottawa in a rented car, an informant walked into a U.S. embassy with a vague but alarming tip that would ricochet in unexpected directions and change their lives

They were four friends bound for Washington, D.C. to witness Obama’s inauguration. But around the same time they left Ottawa in a rented car, an informant walked into a U.S. embassy with a vague but alarming tip that would ricochet in unexpected directions and change their lives

More than a million people stood proudly in the January chill of Washington’s National Mall. The streets of D.C. were filled with 7,500 soldiers, 10,000 National Guard troops and 25,000 police.

The FBI was reported to have 600 agents on inauguration duty, although not all had been assigned to the jubilant crowds. Half a dozen agents had Ahmed and his friends surrounded in his uncle’s living room in the suburbs.

The FBI, Homeland Security and the Metropolitan Police had descended on the home where the Canadians were staying the previous day, guns drawn and sirens wailing. They’d questioned everyone and searched their car. On inauguration day, the agents had returned and the grilling continued: Are you really Canadian? Why are you here? Do you have enemies in Somalia?

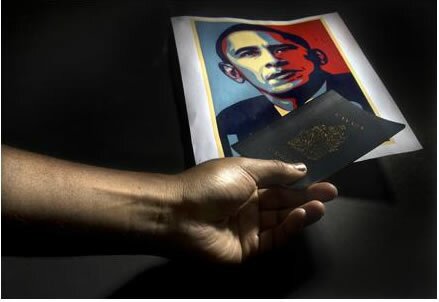

A television was on. They paused to watch as Obama was sworn in.

Ahmed felt joy and confusion. “Most of all, I felt sad,” he says. “We should have been there in the crowd.”

-

What Ahmed and his friends didn’t know was that some time around Jan. 17, 2009, the day they left Ottawa in a rented Chevrolet Impala, an informant had walked into an overseas U.S. embassy with a vague but alarming tip. The warning, which a Canadian source close to the investigation has confirmed to the Citizen, said Canadian disciples of al-Shabaab, the Islamic militant group in Somalia, planned to detonate high-power explosives at the inauguration.

The alert sparked a massive FBI probe. News of the threat leaked almost immediately, although the Canadian angle has only surfaced recently. The FBI soon determined it was a bogus tip, the result of clan rivalries in Somalia — but not soon enough for Ahmed and his friends.

They fear their names are now on security watch-lists. The only two who have travelled to the U.S. since the inauguration were detained at the U.S. border and questioned for hours about what happened in Washington.

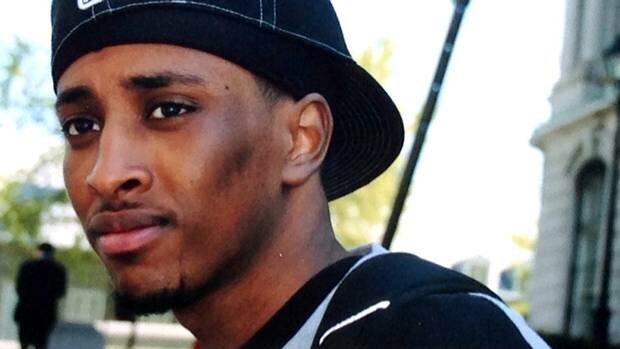

Ahmed is not his real name. He agreed to tell his story only if it left out identifying details. He and his family are deeply fearful of being linked publicly to a terror threat, be it in the secret files of CSIS or the eyes of their friends, neighbours and co-workers.

None of the American or Canadian security agencies involved would comment on Ahmed’s story. But Ahmed wants the story told because he wants to shed light on what happens when you’re collateral damage in the war on terror. He and his friends want back what they had before: Clean records and lives without fear — fear of harassment at international borders, fear of being linked to terrorism, fear of encounters with security and intelligence agencies.

“The FBI told us they were sorry, that it had all been ‘a grave misunderstanding,’” says Ahmed. “I have to make it clear, I don’t object to security agencies doing their job. I’m all for investigating tips. But how credible were those tips?”

-

Ahmed went to Washington because he believes in Obama’s promise of hope. “My parents taught me — ‘Yes, you can.’ If you work hard, plan well and contribute to society, you can do whatever you set your mind to.”

It’s been more than 20 years since Ahmed’s family fled the fighting in Somalia. He has since graduated from an Ottawa university and is working to save money for graduate school. Polite, hard-working and ambitious, he is well-connected in the city and respected for his volunteer work.

He is also a young man of Somali origin, which on its own is enough to make him extremely interesting to the security and intelligence community.

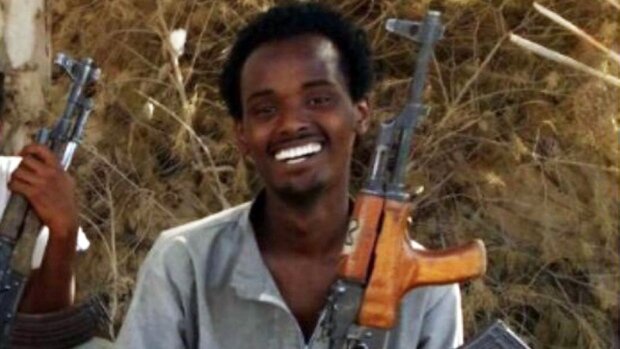

The rise of al-Shabaab — the youth, in Arabic — has put Somali immigrants in the crosshairs of western intelligence agencies. During the past three years, several Americans have reportedly travelled to Somalia to train with the group. It is said that some have accepted suicide missions within Somalia. Several young Somali-Canadians disappeared from Toronto recently. Intelligence sources believe they are al-Shabaab recruits.

In November 2008, two CSIS agents contacted Ahmed. As a young man with a large network, he might hear of growing Islamic radicalism among Ottawa’s Somali youth — would he let CSIS know if he noticed any extremist behaviour?

“I couldn’t even fathom that they felt they had to ask me to keep a watch out,” Ahmed says. “I’d be the first to tell them if I saw something. This is my country, too.”

Ahmed offered to help create dialogue to overcome the mistrust between the security agencies and the Somali community. “They said they’d tried that before in Toronto and it didn’t work.”

Two months later, Ahmed’s aunt and uncle invited him down to Washington for the Jan. 20 inauguration. Ahmed’s uncle, a civil servant, and his wife, a stay-at-home mom with young children, have lived in the U.S. since the 1980s. They had plenty of room for guests in their four-bedroom, semi-detached house on a quiet cul-de-sac in the suburbs.

Ahmed rented a car, picked up three friends and hit the road on Saturday, Jan. 17. They crossed the border with ease and arrived at his uncle’s house late that afternoon.

After dinner, Ahmed and one of his friends drove downtown. They toured the sights, snapping photos on the National Mall, by the Lincoln Memorial and Capitol Hill. The next day, Sunday, all four went back for more.

“It was incredible — like being on Parliament Hill for Canada Day,” says Ahmed. “We were taking pictures with people we didn’t even know just because they were so happy.”

Monday morning over breakfast, Ahmed’s aunt told her guests that two FBI agents had appeared at the house around 11 p.m. the previous night. The agents asked for her husband, who was out, so they presented their cards and asked for him to call. Before leaving, the agents showed the aunt photographs of some Somali men, none of whom she recognized.

“My aunt was shaking when she told us about it,” Ahmed says. “We thought (the FBI visit) was weird, but we didn’t think it had anything to do with us.”

At around 5 p.m., with Obama’s inauguration less than 24 hours away, the Canadians decided to go back downtown. Three were sitting in the Chevy Impala in the driveway, waiting on the fourth, when the air filled with the sound of sirens. Unmarked cars and vans sped onto the cul-de-sac and blocked the driveway. The Canadians heard shouting: Turn off the car. Stay where you are. Hands on your heads.

“In my rear-view mirror I saw a whole bunch of guys dressed head to toe in black — helmets, flak jackets, pants — holding these big guns, running straight at us,” says Ahmed.

Confused, he rolled down the window and poked out his head.

“Is everything OK?”

The FBI agents, led by two men in jeans, were waving off the armed men. “We just need to ask you some questions,” they said, almost apologetically, as they directed the Canadians back to the house.

Inside, Ahmed’s aunt was visiting with a friend and her children. Both women trembled as they ushered their small children to the basement. The four Canadians, plus more than half a dozen agents from the FBI and Homeland Security, crowded into the open-concept living room and dining room.

An FBI agent called Ahmed’s uncle and asked if he wanted to come home or meet elsewhere. He told them he’d come home. They advised him to call when he was close — he’d need an escort to get through the roadblock at the end of the street.

One agent sat with the aunt in her dining room, another sat with the Canadians in the living room. The agent showed Ahmed’s aunt more photos, and she recognized two men: the previous owner of the house, and the uncle’s nephew, who stayed with them for a while.

“They were questioning my aunt about people who had lived in the house before,” says Ahmed. “They asked us what we were doing in the United States, how long had we lived in Canada and if we were planning on attending the inauguration.”

Every now and then, a new agent would arrive and ask the same questions.

Even as he handed over his passport and the rental agreement for the Impala, Ahmed didn’t make a connection to his CSIS encounter months before. “They seemed to be more focused on the homeowners,” he says. “I figured it was a misunderstanding.”

Ahmed says he gently chided the lead FBI agent for the unnecessary display of force. The agent apologized but did not explain.

About an hour into the questioning, an FBI agent asked to search the house. Of course, replied Ahmed’s uncle, assuming you have a warrant. They didn’t. No search.

A Homeland Security officer asked to search the Impala. They didn’t have a warrant for that, either, but Ahmed relented. Outside he found the car surrounded by four FBI agents.

“All I could think was that maybe one of them planted something,” says Ahmed. “My heart was pounding. Then I told myself I’d been watching too much Prison Break.”

The agents shone a flashlight in the trunk, flipped through some textbooks in a bag and said they were done. Ahmed and his friends asked again what it was all about.

“The Homeland Security guy says, almost joking, ‘Do you have anybody who hates you back home in Somalia?’” says Ahmed. “I remember one of us said, ‘Are you serious?’ We told him we all came to Canada as kids, we haven’t been back to Somalia, Canada is all we know.”

Finally, Ahmed recounts, three hours after arriving, the lead FBI agent apologized again and told them there’d been “a grave misunderstanding.”

“He thanked us for our co-operation, told us we were free to go, and even started suggesting tourist spots we should check out.”

Once the agents were gone, Ahmed’s uncle opened his laptop to his homepage — the local newspaper. “It was the big ‘Aha’ moment,” Ahmed recalls. The screen revealed news that security agencies were investigating a possible threat to the inauguration by Somali militants.

“That was the first I ever heard of al-Shabaab,” says Ahmed.

It was now about 8:30 p.m. Exhausted and upset, the Canadians were still determined to make the most of their time in D.C. Against his uncle’s wishes, Ahmed and the others got back into the Impala to head downtown. They were barely out of the neighbourhood when they realized they were being followed. They counted seven unmarked sedans and SUVs.

“It was so obvious, we were all laughing,” says Ahmed. “But it was also frightening. We’d been told we’d be left alone.”

They didn’t notice anyone following them as they walked around downtown, but on the way back to the suburb that night, the unmarked cars followed them through a McDonald’s drive-through. Once home, the cars sped off, leaving one to park in front of the house.

“We talked over and over about whether or not to go to the inauguration,” says Ahmed. “What if something happened? My uncle said, ‘You came all this way to be a part of this historic moment. Don’t let this experience spoil it for you.’”

-

Tuesday, Jan. 20. Inauguration day. People across Washington and beyond were on the move early to get a good spot on the National Mall. Ahmed’s uncle gave the Canadians a lift to the nearest subway station, their excitement building even though they noticed right away that they were being followed.

“My uncle drops us off and drives away,” says Ahmed. “We walk toward the Metro and suddenly a police officer runs towards us, calling out, ‘Hey guys, stop.’”

It’s as close as they got to the inauguration.

“Some Secret Service agents asked me to stop you,” Ahmed recalls the officer saying. “We stand there for a few minutes, embarrassed and humiliated as all these people go past us heading downtown, staring at us.”

The Canadians were sent back to the house for more questions. In the dining room they were greeted by a handful of the same agents from the day before, plus a few new ones from the FBI, Homeland Security and the Secret Service. Again they asked to search the house, again with no warrant. This time, Ahmed’s uncle conceded.

The Canadians were questioned in the living room. The aunt and uncle were interrogated in the dining room. They showed the aunt and uncle more photos of Somali men; they recognized the same two as the day before.

Meanwhile, the same questions were directed at the Canadians: What have you been up to in Washington? Where did you rent the Impala? Are you really Canadian citizens?

Ahmed’s aunt made tea for the agents, his uncle cracked jokes. But as the clock neared 11, his uncle asked the lead FBI agent if they might stop to watch Obama take the oath of office. The search was suspended and some of the agents joined the family in front of the TV.

“I remember total silence in the living room, even the kids,” says Ahmed. “But in the kitchen, a couple of the FBI guys were whispering and writing on their BlackBerrys.”

The search resumed after Obama took the oath of office, but soon after 1 p.m. — more than three hours after they’d arrived and mere minutes after the end of the inaugural ceremony — the agents looked at their BlackBerrys, then at each other, and declared they were done.

“They hadn’t even finished the search,” says Ahmed. “They apologized some more and said everything was over, ‘You won’t see us anymore.’”

But it wasn’t over. On the way out for lunch, the family spotted an unmarked car. Ahmed’s uncle approached the agent, who said he’d been instructed to follow “the kids from Canada.”

The agent, who sat on the other side of the restaurant, came over in the middle of the meal.

“It’s really over now,” he said. “You won’t see me again.”

But it still wasn’t over.

The Canadians decided to get home as quickly as possible. The next day, they had a nerve-wracking drive north, relaxing only once they crossed back into Canada with no problems. When Ahmed returned the rental car, he was told that RCMP officers had been at the rental agency on Monday, asking questions of the clerk, also of Somali origin.

“They wanted to know if I was a good guy, if I had a beard, if I go to a certain mosque,” says Ahmed.

In the year since the inauguration, two of the four Canadians have been stopped at the U.S. border. One was arrested crossing into Detroit, held for six hours and questioned repeatedly about Washington. Another was detained at Ottawa airport for two hours while heading to New York on business, and also grilled about Washington.

“This is what happens to us, even though we were told we’d done nothing wrong, that there was a ‘grave misunderstanding’ and thanked for our co-operation,” says Ahmed. “What does this mean for me and my family, my future?”

Ahmed and his friends know their story poses more questions than it answers. Why them, why so much force, why the lingering suspicions?

Learning a few weeks ago that the al-Shabaab tip had been deemed bogus, Ahmed was relieved, and frustrated.

“Now I wonder, will there always be a question mark next to my name, because of a bogus tip from the other side of the world?”

____

Ottawa Citizen

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar