High Court Addresses Samatar vs Bashe case

The Supreme Court heard arguments Wednesday over whether foreign leaders are entitled to legal immunity in the U.S. for their official acts, in a case that some justices suggested could hold ramifications for former American officials.

The court is seeking to reconcile two U.S. laws in apparent conflict.

The Torture Victim Protection Act of 1991 authorizes lawsuits against people who allegedly committed torture or extrajudicial killing “under actual or apparent authority…of any foreign nation” when the home nation lacks adequate remedies for such offenses. But the 1976 Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act exempts “agencies” and “instrumentalities” of foreign governments from being sued.

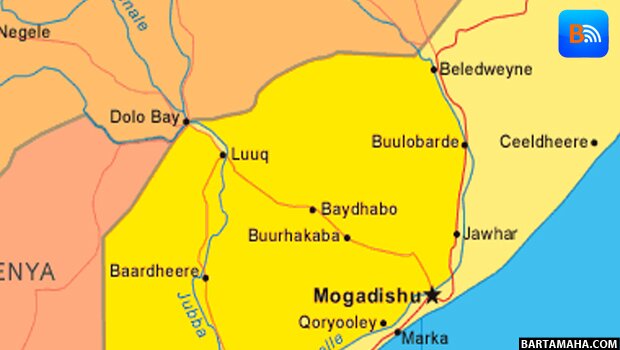

The case involves a former Somali prime minister, Mohamed Ali Samantar. Five Somali natives, including two U.S. citizens, claim that they or their relatives were abused or killed by forces under Mr. Samantar’s command.

Mr. Samantar, who now lives in Fairfax, Va., contends that because he was prime minister or defense minister from 1980 until the Somali regime’s 1991 collapse, he was an “instrumentality” of government and thus immune from liability.

In a ruling last year, the Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed. The Richmond, Va., court said the Immunities Act was designed to cover entities such as national airlines and other state-owned businesses, not individuals.

Other appeals courts have read the Immunities Act more broadly, and the Supreme Court seemed similarly divided over how to construe the law.

Shay Dvoretzky, a lawyer representing Mr. Samantar, said there was no way to distinguish between a foreign government and the individuals who ran it. Congress immunized “foreign officials for acts taken on the state’s behalf, because such suits are the equivalent of a suit against the state directly,” he told the court.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg didn’t seem persuaded, saying: “The act is aimed at torturers. The remedy comes out of the private pocket.”

Patricia Millett, an attorney representing the plaintiffs, said that if Mr. Samantar was right, then the Torture Victim Act “was a very empty statute.”

Chief Justice John Roberts countered: “The only way a state can act is through people. And you are saying: ‘Well, the state is insulated, but the people who do the acts for the state are not.’ I don’t see how that can work,” he said.

Deputy Solicitor General Edwin Kneedler said the law’s ambiguity was intended to leave discretion with the executive branch, which could advise courts whether any particular torture lawsuit should be allowed to proceed. “There are a lot of diplomatic sensitivities about whether immunity should be recognized in a particular case or not,” Mr. Kneedler said.

Justice Antonin Scalia questioned whether the executive branch should be given such authority, suggesting that if other countries adopted that standard it could put U.S. officials at risk.

Last year, Baltazar Garzon, a Spanish magistrate, opened an investigation into torture allegations against six former Bush administration officials, including two aides to former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld.

Justice Scalia said to Mr. Kneedler, “And what you say is that that’s perfectly okay. It’s up to the Spanish government” to block the magistrate from proceeding, “and if it doesn’t, it’s perfectly okay?”

No, said Mr. Kneedler. “The United States would…assert immunity, and expect that to be respected,” he said.

A decision in Samantar v. Yousuf is expected before July.

____

LA Times

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar