Going back to the land: Somali Bantu refugees learn organic farming business

PAUMA VALLEY — Something more than carrots and kale is growing at Tierra Miguel farm in Pauma Valley.

PAUMA VALLEY — Something more than carrots and kale is growing at Tierra Miguel farm in Pauma Valley.

The future is taking root.

Once a week, a group of Somali Bantu refugees drives 45 miles from the City Heights neighborhood of San Diego to this remote agricultural valley in North County.

Their mission is to learn local growing techniques and start an organic farming business that can help them support their families.

Organized by the International Rescue Committee, the program started in October and is designed to help refugees adapt the traditional farming methods they used before civil war drove them from their East African country nearly two decades ago.

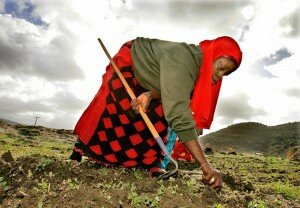

As Sitey Mbere pulled weeds along a row of lacy carrot plants last week, she recalled the several acres of sesame, nuts and corn she once grew. She said through an interpreter that she is happy to be able to farm again.

“We’re remembering Somalia and what we were doing there,†Mbere said in the Kizigua dialect of Swahili.

Like the other 18 people in the program, Mbere fled Somalia after war erupted in 1991 and spent a dozen years in refugee camps in Kenya before coming to the United States in 2004.

As a minority group in Somalia, the Bantu had long been discriminated against and marginalized. War and continuing chaos heightened the violence against them, forcing them to flee.

In 2004, about 480 Somali Bantu refugees came from camps in Kenya to San Diego. Nearly one-third have since moved away because of the region’s high housing costs and recession-plagued job market that is especially hard on refugees with little education and English-speaking skills, said Hamadi Jumale, president of the Somali Bantu Community Organization of San Diego.

Poverty often leads to poor nutrition, Jumale said.

“It’s very hard for people to get healthy because of all the (cheap) junk food,†Jumale said. “A lot of the food we’re getting is not organic.â€

The International Rescue Committee, which assists people fleeing violent conflict, has received two federal grants to help boost nutrition and income in San Diego’s refugee community.

The agency recently opened its 2.3-acre New Roots Community Farm in San Diego’s Chollas Creek neighborhood, dividing the land into 80 small plots where refugee families grow produce for home consumption.

Many of the Somali Bantus with plots said they wanted more space to grow crops to sell. That led to a partnership between the Rescue Committee and the Tierra Miguel Foundation, which operates an agricultural education center and organic farm in Pauma Valley.

“We wanted a training program that would give the refugees skills to sell produce at farmers markets,†said Jaime Garza, manager of the Rescue Committee’s Refugee Entrepreneurial Agriculture Program.

Tierra Miguel farm manager Milijan Krecu said 5 acres have been set aside for the program, which will bring in a new refugee group every 15 weeks. The initial course focuses on choosing crops, preparing the soil and learning organic methods of growing produce by hand. Instruction on planning, bookkeeping and marketing also is on the agenda.

Later courses may focus on identifying the best moneymaking crops, controlling insect pests, and using tractors and other timesaving equipment.

“We didn’t want to, in the process of teaching them, alienate them from the practices they know and love,†Krecu said. “What we would like to do is have the first group help teach the second group, while the first group also learns more complicated work.â€

The program is still being developed, and Garza said he hopes to find acreage to farm closer to the refugees’ homes.

“We need to get the word out that land is needed,†he said.

On Tuesday, men and women chatted as they pulled weeds and thinned the small plants that had sprouted in the rich soil over the previous week or so. A chill wind blew through the narrow valley, where lush citrus and avocado groves climb the hillsides.

Halima Sowa said she and her six children came to San Diego in 2004 after 12 years in a refugee camp in Kenya. Her husband was killed when he left the camp to visit Somalia, she said.

Although coming to San Diego meant safety, trying to do everyday tasks such as finding a grocery store and buying unfamiliar food was overwhelming, Sowa said.

“I’m feeling better now. The IRC helps a lot,†she said in Kizigua, translated by fellow refugee Salah Muganga.

Sowa’s four youngest children, who range in age from 8 to 20, live with her in City Heights. She said she makes sure they have food, clothes and time to do their homework. They tell her they want to become a teacher, a doctor or maybe a pilot.

And she tells them about the food she once grew in Somalia — beans, corn, pumpkins, watermelon. Sometimes she brings them to the New Roots garden and to the Tierra Miguel farm.

Muganga said that’s not uncommon for the Somali Bantu mothers.

“They don’t want their kids to forget this,†he said, nodding toward the earth.

____

Source: Sign on San Diego

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar