For Novice Journalists, Rising Risks in Conflict Zones

OTTAWA — Amanda Lindhout was a waitress at an Irish pub in Calgary, Alberta, with a dream of becoming a journalist. But Ms. Lindhout, who has no formal journalistic training, did not join the ranks of citizen journalists who blog about their communities. Instead, she used her earnings from the bar to finance reporting trips to several of the world’s most dangerous war zones.

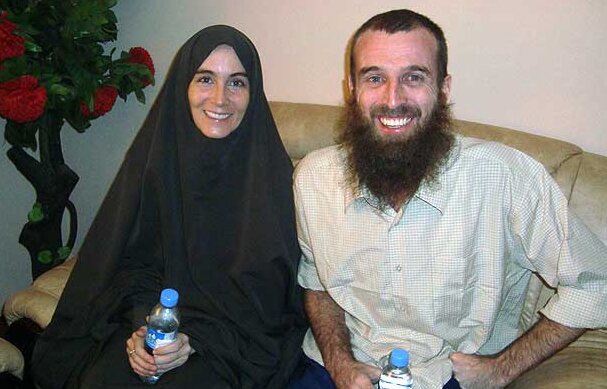

Last week, Ms. Lindhout and her Australian companion, Nigel Brennan, were released by Somali kidnappers, who had held them for ransom and abused them over the last 15 months. Despite the risks, suffering and capture, which reportedly ended with a payment of $600,000 raised by their families and friends, Ms. Lindhout’s achievements as a journalist have been modest.

She wrote a weekly column for her hometown newspaper in Alberta for six months, freelanced from Iraq for Press TV, an English satellite channel financed and influenced by the government of Iran, and produced a handful of reports for a cable news channel in France. At the time of her capture, Ms. Lindhout appears to have had no assignments other than her work for The Red Deer Advocate, a small daily that generally relies on wire services for coverage of other parts of Alberta, let alone the rest of the world.

Wars have long provided a way into journalism for some adventurous aspiring reporters (as well as death, kidnappings and injury for others). And courageous, if inexperienced, freelancers have brought important stories to light that might otherwise have gone unreported.

The Internet, digital photography and affordable, high-quality video cameras now make it easier than ever for anyone to report from just about anywhere in the world. A proliferation of television outlets occurring at the same time that large news organizations are cutting back on reporting potentially creates a bigger market for reporting by newcomers.

But those developments also come as, several analysts say, reporting has never been more dangerous, for everyone.

“This business of inexperienced people going into conflict zones without proper preparation or training is increasingly worrying,†said Rodney Pinder, the former global editor of Reuters Television who is now the director of the International News Safety Institute, a charity financed largely by news organizations and based in Brussels.

“There’s a lot of ignorance behind some of this behavior, because people don’t realize how dangerous it’s become for journalists in the world today,†he said. Mr. Pinder’s organization estimates that about 1,500 people have been killed while working for news organizations in the last decade.

Ms. Lindhout and Mr. Brennan remained hospitalized on Sunday in Nairobi, Kenya, where they were taken after their release. Ms. Lindhout was expected to be released on Sunday. Neither they nor their families were speaking to reporters.

But interviews with former associates of Ms. Lindhout and accounts by Canadian news organizations portray her as a passionate, tough-minded and curious young woman. Paul Vickers, a restaurant and bar owner in Calgary, said that Ms. Lindhout worked long enough at one of his pubs to pay for a trip and “when she ran out of money, she came back here.â€

Several news reports indicated that Ms. Lindhout had traveled with Mr. Brennan to Somalia to report for France 24, a news channel owned by the French government.

While Ms. Lindhout had filed a few reports to the network from Iraq, Nathalie Lenfant, a spokeswoman for France 24, said the network had turned down her proposal to act as a correspondent from Iraq as well as her subsequent suggestion that she report from Somalia. During her capture, Ms. Lenfant said, France 24 decided to confirm that Ms. Lindhout had been on a freelance assignment, even though that was not the case.

“We thought it would be better if she could be seen to be part of the structure of a larger company,†Ms. Lenfant said.

Robert Draper was already in Somalia on an assignment for National Geographic when Ms. Lindhout and Mr. Brennan arrived. Mr. Draper said that it was apparent that she had been the driving force behind their trip. She had met Mr. Brennan backpacking in Ethiopia. While Mr. Brennan was in Somalia as a photographer, Mr. Draper said, it was not clear whether he had ever sold any photographs.

“She was eager to make a name for herself, and I don’t say that as a negative,†Mr. Draper said. “But a lot of the early and intermediate steps one does to become a journalist, she bypassed. Amanda was very eager to go where the action was.â€

Mr. Draper said that Ms. Lindhout took several precautions, including hiring a local adviser, or so-called fixer. She also listened to advice from the adviser as well as one retained by National Geographic as they repeatedly rejected successive travel plans as excessively dangerous.

But Mr. Draper said it was apparent that Ms. Lindhout’s excursion had lacked the degree of planning he had undertaken along with a photographer for the magazine, Pascal Maitre. Her limited finances also restricted the number of armed guards she was able to hire. Journalists from large news organizations will hire up to 10 gunmen, a private army of sorts, at a total cost of $300 to $1,000 a day.

No amount of protection can guarantee a reporter’s safety in Somalia, a place Mr. Pinder describes as too dangerous for even many experienced journalists. But when Ms. Lindhout and Mr. Brennan left Mogadishu to see a squalid camp where thousands of refugees sleep in bubble-shape huts made from twigs and plastic bags, they were traveling into a dangerous border region where control passes between the government and warlords.

Mr. Pinder’s group and other organizations have programs for improving the safety of freelancers working in war zones. But he is at something of a loss about how to protect people like Ms. Lindhout and Mr. Brennan.

A few years ago, he said, several large broadcasters tried to reach an agreement not to buy video from unassigned, unaffiliated freelancers, so as to discourage excessive risk-taking. But that collapsed when it became apparent that no news organization would actually turn down images from a major news event.

Given the increasing danger, Mr. Pinder said he hoped that novice journalists would invest in war zone safety training before leaving home and make their first forays into dangerous areas with experienced reporters rather than on their own.

Whatever the risks, Mr. Pinder said it was unlikely that aspiring reporters would end their efforts to learn on the job in war zones.

“The main driving force is instant fame or instant recognition of some sort,†he said. “It’s a way of breaking into the business at a very competitive high-end level. And what is a journalist at the end of the day?â€

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar