Empathy Is a Prerequisite

Bartamaha _Somalia:- This week, BU Today presents “Reaching Out,” a five-part series on the many ways that the Boston University community works to ease the hardships of immigrants and refugees in the Boston area.

Bartamaha _Somalia:- This week, BU Today presents “Reaching Out,” a five-part series on the many ways that the Boston University community works to ease the hardships of immigrants and refugees in the Boston area.

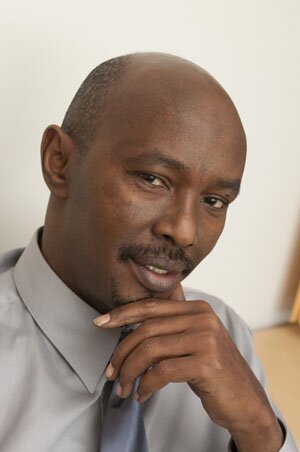

Even after six years in America, the trappings of daily life here can still confound 52-year-old Somali immigrant and skilled carpenter Mohamed Haji, who is traveling the slow, obstacle-riddled road to U.S. citizenship. Haji finds help in many forms, and very often these days it is in the form of fellow Somali Ali Abdullahi (SSW’13), who works as an immigrant outreach coordinator at Massachusetts General Hospital’s busy social services office in Chelsea, Mass.

“Ali reads for me,” says Haji, pulling a rumpled Comcast bill from his pocket. “Ali say, go here, go here, go here. Ali everything.”

Abdullahi began working right after college in his native Somalia, assisting refugees from Ethiopia’s civil war. When civil war also engulfed Somalia he fled to Kenya, where he offered his services to the United Nations at its headquarters there. In 1996, Abdullahi and many members of his neutral clan were granted permission to resettle in the United States. He came to Boston with three siblings.

A friend working in neighborhood development told Abdullahi about BRIDGE, a School of Social Work master’s program designed to help recent immigrants serve their communities here. Already in his early 40s, Abdullahi says he wondered at first if he was too old for the program. Then he worried about how in the world he would pay for it. Then he applied.

Today, Abdullahi is managing to pay his way through the master’s program, juggling course work with a job helping new immigrants and refugees make their way, from finding English classes for adults to helping children adjust in their new schools. Depending on his course load, by 2013 or a bit sooner, he will be equipped with the knowledge and official credentials for a career decades in the making.

BRIDGE (Building Refugee and Immigrant Degrees for Graduate Education) is an outgrowth of SSW’s Refugee and Immigrant Training Program, launched in the early 1990s to recruit immigrants for careers in social work, says BRIDGE coordinator Lee Staples, an SSW clinical professor of social work. When the school considered phasing out the program 10 years ago, it was Staples who fought to keep it alive, using focus groups to develop a program that shepherds applicants from orientation to preadmission to study for an MSW and beyond to career development.

Since the program’s inception, Staples and his staff have cast an increasingly wide net for applicants, sending out 1,000 brochures last year alone to ethnic radio programs, churches, and community centers. Some applicants appeared through word of mouth. Some, like Abdullahi, were culled from open, cost-free orientation groups of 10 to 20. Only about five students are accepted each year, with at least two completing their degrees. Students are required to have refugee or asylee status or green cards, if not U.S. citizenship, and they must take a preparation course, rounded out with mini workshops and social events, to ease their transition into the master’s program. In the last few years, says Staples, BRIDGE students have come from every corner of the globe, including Cambodia, Cameroon, Cape Verde, China, Colombia, Congo, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Haiti, Iran, Morocco, Puerto Rico, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, Uganda, and Vietnam.

Staples has found that the students themselves underscore the cultural differences their countrymen face here, which makes a strong case for the need to train immigrants to serve their communities. Any Haitian, for example, would understand why students from that country might initially sit silently through classes, rather than ask questions; in Haiti, as in many countries, it’s considered disrespectful to question a teacher.

“Here, you get points for talking in the classroom,” says Abdullahi. “At home in Somalia you get punished. I’m still adjusting to that; when you’ve been told for 16 years not to talk in class, you can’t just start blabbering.”

Abdullahi’s work as an immigrant outreach coordinator in Chelsea puts him in a position to help struggling families from his native Somalia as well as from Latin America and the Middle East. “I work with refugee adults and kids,” says the tall, elegantly dressed master’s student in his fluent and precise English. “I help them with anything they need—I call landlords, set up doctor appointments, help them get welfare benefits and food stamps.”

Abdullahi’s work as an immigrant outreach coordinator in Chelsea puts him in a position to help struggling families from his native Somalia as well as from Latin America and the Middle East. “I work with refugee adults and kids,” says the tall, elegantly dressed master’s student in his fluent and precise English. “I help them with anything they need—I call landlords, set up doctor appointments, help them get welfare benefits and food stamps.”

He works with eight schools, helping an average of five families a day, he says, with home visits and informal meetings a routine part of his schedule.

“I have a pager that doesn’t stop ringing,” he says. His Chelsea office “is the first place they come after their arrival. The resettlement agencies send them here.”

In Chelsea, where the first language of 85 percent of public school students is not English, refugees can find affordable housing, as well as services like those offered by MGH. They can also get to downtown Boston, where they typically travel for English classes. Abdullahi says that when newly arrived refugees do find jobs, it’s more about survival than training or finding the perfect career fit. “I know a Somali doctor who is a cashier at Wal-Mart,” he says. “Maybe the next generation will assimilate, but it may be the next next generation. With Somalis, the language, culture, dress code—everything is different.”

It’s the fathers who seem to have the most trouble adjusting, he says. Authority figures both at home and in the community in their native countries, here they must rely on their children to translate for them, act as intermediaries in financial matters, and make sense of American popular culture.

“The kids learn languages faster than the parents,” Abdullahi says. “Parents feel a heavy burden of responsibility for their kids, and here they feel helpless.” Haji, for one, speaks of “getting back his respect” when he finally landed a carpentry job. “If a man works, he has his family’s respect,” he says. “In the refugee camp in Kenya, I roamed around with my carpenter’s tools and couldn’t find work, and I’d come home tired and didn’t earn a penny. Here, I know I come back home with money and self-respect.”

But many other immigrants don’t fare as well. Abdullahi says he sees a significant amount of depression among refugees, who often feel invisible or misunderstood. He says Somalis, particularly the men, draw comfort from gathering for tea at places like Roxbury’s Butterfly Café, where they can “be with someone facing the same obstacles.” Abdullahi himself, a member of Somalia’s Ashraf clan, grew up in the cosmopolitan coastal city of Kismayo, and says he often longs for the place. But like most of Somalia, he says, it is now in ruins.

An important part of his job is outreach in Chelsea’s public schools, where the cultural divide is particularly pronounced. “Most of these kids didn’t have any school back home, and they are placed here according to age,” he says. “I know a kid in middle school, he’s 12, who never held a pen.” Integrating these children into American schools is difficult, he says. “It’s overwhelming, it’s unrealistic, but they get a lot of support to lift them up a little. ”

He recently had to explain to school officials that a Somali pupil’s habit of hoarding food in his locker, although against school rules, was far from malicious—the boy had spent years struggling with near-starvation in an overcrowded refugee camp. “Some of these kids were born in refugee camps,” he says. “The teachers thought the kids were hoarding food for fun. I was hired to defuse tensions, smooth the transition, and stop any miscommunication.”

Abdullahi has worked with the Chelsea schools on a range of matters, including accommodating Muslim children fasting through the holy month of Ramadan.

“Education is totally different here,” he says. “I needed someone to show me the ropes.” For that, he thanks “Dr. Lee,” as he refers to Staples, and BRIDGE. “Ali has done a remarkable job reaching out to the Somali Bantu community in Chelsea,” says Staples. “Previously this newcomer group had very limited contact with the medical and mental health services at the MGH clinic. Ali was able to connect with key community leaders, establish trust, and open up lines of communication, which led to much fuller utilization of MGH services—a win-win outcome for both the Bantu and the clinic.”

Like other BRIDGE students, Abdullahi will become a powerful role model when he earns his degree, Staples says. Abdullahi lives for the day when his name will be followed by “MSW.” And in a rare show of self-assurance, he says that his long record working across languages and cultures is at least comparable to most licensed social workers’ experience. When it comes to working with Somali immigrants, social workers “can’t accomplish as much as I can,” he says. “But when I get my degree, I will be the social worker. That is my drive.”

Tomorrow’s feature has two components: one examines the School of Law’sAsylum & Human Rights Clinic (AHR), where law students represent asylum seekers and others involved in immigration and humanitarian cases; the other looks at the interpreter certificate program at the University’s Center for Professional Education, which trains multilingual students in community, legal, and medical interpreting.

=====================

Source:- Bu today

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar