Changing face of Canada ‘cowboy city’

The small Canadian cattle-ranching city of Brooks, in south-eastern Alberta, is preparing to celebrate its 100th anniversary next year.

The small Canadian cattle-ranching city of Brooks, in south-eastern Alberta, is preparing to celebrate its 100th anniversary next year.

Painted murals depicting a proud western heritage of cattle farming, cowboys, ice hockey and the oil and gas industry have appeared throughout the city.

A century ago, immigrants cried when they reached Brooks because the landscape was so dry and inhospitable before irrigation helped it to become an oasis in the desert for cattle ranchers.

Decades ago it was the promise of farmland that attracted immigrants to Brooks; today it is the prospect of work at the local meat processing plant, XL Foods Inc Lakeside Packers.

About 10 years ago, the company started hiring new immigrants and refugees who had recently arrived in Canada.

Alberta’s oil patch with its high salaries had enticed locals away and the plant could not find enough Canadian workers.

Word spread across the country that newcomers could get a job quickly at the meat processing plant in Brooks without speaking English or having any specific skills and that starting pay would generally be $13 an hour (£7).

The job attracted many immigrants and refugees from Africa, the Middle East, Asia and South America who had left their country for a better life in Canada.

“People know (it) doesn’t matter what your language, doesn’t matter where you’re from in the world – you show up tomorrow and you can go to work at Lakeside Packers,” said Brooks Mayor Martin Shields.

XL Foods is one of Canada’s largest beef producers, employing 2,400 people; some 60% of the workforce are immigrants, including refugees and temporary foreign workers.

Despite the global economic downturn, business is doing well and the plant is still hiring.

Unfamiliar

The influx of immigrants has changed the fabric of this old ranching town.

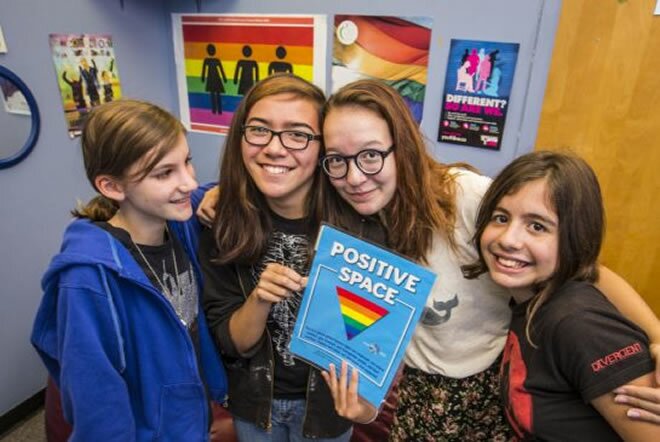

New ethnic stores have opened and schools now offer English as a second language classes.

On the main street, people from different cultures mix together and teenagers born on different continents become friends while playing basketball and skateboarding.

For many other cities this is not unusual but for Brooks, which for decades was mainly a white prairie town, this change is profound.

“For the people that have lived here for a long time, it is new and different and sometimes there is a lack of trust,” said teacher Joe Buckler.

“And there’s the old ‘if they don’t like it here let then go back to where they came from”.”

For many of the city’s residents, the places where the immigrants have ‘”come from” are unfamiliar.

According to Joe, even the teachers in Brooks are getting social and geography lessons.

“I’ve got some kids from the Sudan, we assumed that they should be friends and we put them in the same class,” he said.

“And we find out they are from different parts of Sudan and if they were still in Sudan they would be in opposite armies killing each other and we’re throwing them into the same class expecting them to be friends. So those things are challenging.”

It is not just the locals who have to adjust to the changes.

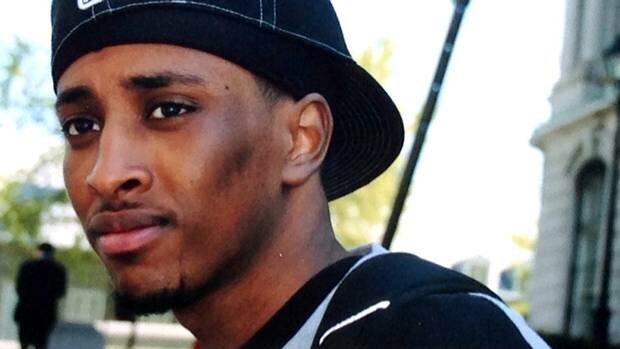

Andres Iwaegbe, 17, moved from Nigeria to Brooks to join his father at the meat processing plant.

“I didn’t quite know that Alberta was like the cowboy, redneck stuff,” he said.

“I made some friends and they told me their ways and I’ve gone to people’s farms and helped them out so that’s cool.”

Andres’s friend, Jonathan Gasirabo, moved to Brooks from Rwanda.

He said most people were nice to them but that some of the older generation who have lived in Brooks for years could be unwelcoming.

“I’ve seen some old people that just look at you weirdly,” said Jonathan.

“It just means that they are not aware of the change, they are just ignorant. I think because they are done learning.”

Heritage

The Canadian Red Cross branch in Brooks has gone out of its way to make sure that locals understand where the newcomers are coming from.

For the past two years, they have set up simulated refugee camps for people to visit.

“Some didn’t understand or didn’t know what a refugee was in the first place so it was a sharp learning curve for them,” said Biftu Abdalla of the Red Cross.

“We put people through the camp with different profiles, so all of the profiles are real people with real stories and real outcomes at the end.

“They went through the camp as a refugee and then at the end were told what happened to the refugee.

“They went through the camp as a refugee and then at the end were told what happened to the refugee.

“A lot of the kids were quite shocked by the outcomes.”

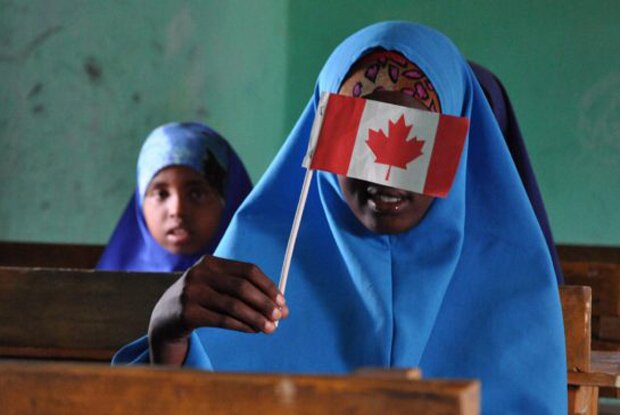

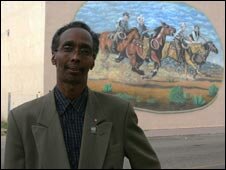

Immigrants like Ahmed Kassem from Somalia have also started their own groups in Brooks to help newcomers to cope with their new lives in Canada.

Ahmed’s organisation, the Rainbow Coalition for Human Development, tries to help new immigrants understand that the Canadian police can be trusted.

“The police they have seen in their homeland is totally different than the police in this society.

“When the police stop a car they will start shaking even if they have everything with them, they have their licence, they have everything (but they are afraid) because that trust is not there.”

The city continues to hold multi-cultural exhibitions that aim to teach everyone about the different cultures living together in the neighbourhood.

Jackie Murray, 82, said initiatives like the painted murals depicting the history of the city do help newcomers understand the very different world they have moved to.

“They go to that wonderful mural of the four cowboys and they see our western heritage and they picture themselves on a horse being a cowboy,” she said.

Jackie pointed out that this was not the first time Brooks has experienced an influx of immigrants.

“The cowboys that came in the early days were either English or Scottish and then we had an influx of Hungarians,” she said.

“The new immigrants will be the next phase of our heritage.”

_______

Source: BBC English

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar