Back to the future: The challenges facing Somalia’s returning diaspora

The remains of a church near the waterfront in Mogadishu, a city that might be emerging from decades of war and neglect. Michelle Shephard / Toronto Star via Getty Images

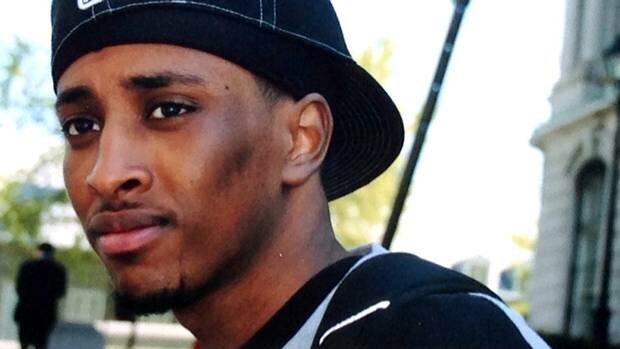

“Whenever you move around, you worry about what will happen to you,” says Abdullahi Nur Osman, who recently moved back to his home country, Somalia. “The security situation is a big worry.”

For the past 20 years, Somalia has been a byword for chaos. In 1991, after the central government fell, the entire economy and political system collapsed. Anarchy and civil war ensued. For years, the capital Mogadishu – once a vibrant seaside resort – has been home to bombed-out facades of buildings. Houses and shopfronts, though painted in bright colours, are pocked with bullet holes.

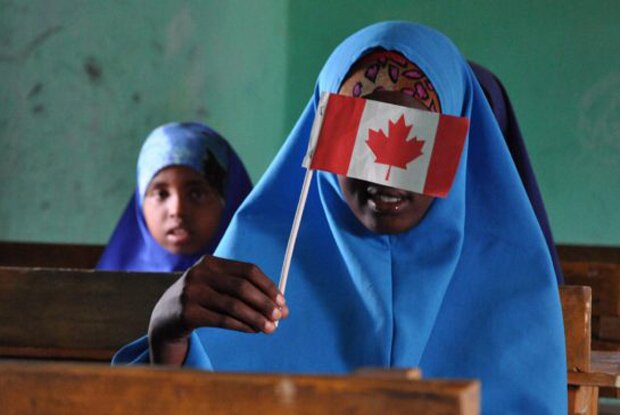

However, if Somalia’s government is to be believed, the country long known as the world’s most failed state is making tentative steps towards recovery. A permanent federal government has been in power since autumn 2012, and the country is gearing up for democratic elections in 2016. Al Shabab, the hardline Islamist rebel group, no longer controls Mogadishu, although terrorist attacks are frequent. Government buildings are the main focus – recent incidents included an attack on the intelligence headquarters and a major prison, and the president’s residence is often targeted. Foreigners and wealthy citizens face the risk of kidnap by terrorists or armed groups.

Despite these dangers, members of Somalia’s huge global diaspora are returning in significant numbers. This has been actively encouraged by the government, which in 2012 announced that Mogadishu was “open for business”. Osman, who lived in London for a decade, is now the president of the Hormuud Telecom Foundation, the corporate social responsibility wing of Somalia’s largest company. “I realised there was a need to go back, to share my expertise and join those rebuilding the country,” he says. Like him, many who have left their adopted homes in the west want to reconstruct Somalia – but they are also drawn by the opportunities available in a country where regulation is practically non-existent and where the lack of an education system puts anyone who has been abroad at a distinct advantage. But, with large swathes of Somalia still controlled by Al Shabab, and Mogadishu’s fragile peace maintained by a heavy African Union military presence, is it a good idea to return, and does the diaspora really hold the key to Somalia’s recovery?

The long, messy conflict in Somalia – which saw warring tribes pitted against each other before Al Shabab came into the fray – means that infrastructure is practically non-existent. Just 10 per cent of Somalia’s roads are paved, while 95 per cent of the country’s 10 million inhabitants have no electricity. The surge in diaspora returns has triggered some instant, visible changes. Construction has restarted in Mogadishu; the colourful shopfronts are no longer just shelled-out facades, but functioning businesses. Hotels and restaurants are springing up. Solar-powered street lights have brought Mogadishu out of darkness. And many hope that the enlargement of the private sector will aid political stability. The government certainly wants to promote the image of an economic renaissance in Mogadishu, in order to attract international investment for desperately needed energy and transport projects.

Maimuna Mohamud is a Somali-American who recently moved back to work for the Heritage Institute, a think tank. “I’ve been based in Mogadishu since February – a really difficult period,” she says. “A lot of people have felt let down by the recent attacks and insecurity in the city. But you keep in mind the reason why you are in the country, you try to be careful and you stick it out.”

Mohamud recently carried out research into the motivations of the returning diaspora. “It’s not a decision people make lightly, but they were primarily going back to contribute to the development and reconstruction of Somalia,” she says, noting that although the government has actively encouraged the physical return of Somalis, there are often tensions with locals who have never left. Members of the diaspora earn much higher salaries than locals for the same work. There is resentment about people returning from long stints abroad to work in politics without understanding the dynamics on the ground. “A local man told me that he doesn’t like diaspora because if ‘something happened tomorrow, then they would head to the airport, leave the country and leave us again’,” she says. “It tells you about the deeply rooted tensions.”

For the most part, locals appreciate diaspora investment in business and the jobs in construction and services they bring. In recent years, eye-catching, whimsical initiatives in Mogadishu have made international news: the first dry-cleaning business to open in the city, the first taxi firm, pizza delivery restaurant or florist. But it is debatable how useful these services are. “This is mostly business generated by the diaspora and directed to the diaspora,” says Roland Marchal of CERI, a French research centre. “Dry-cleaning, for instance, is irrelevant to most people in Mogadishu, who do not need to wear suits. There are many new restaurants and hotels, but the prices – $10 or $15 [Dh37-55] for a meal – are too expensive for local people to pay. Construction is booming and rehabilitation is taking place, but there hasn’t been a second step.”

He attributes this to ongoing security problems. “The situation is unsettled, so it’s very risky to go beyond trade. Whatever the international community say, Al Shabab is still there. That’s why people are reluctant to go beyond services that do not need huge investment.”

The basic costs of existing and doing business in Somalia are high; not only are private security costs significant, but there is also practically no electricity grid after years of war and diesel is expensive. But there’s an upside to this lack of infrastructure, too. “Diaspora are very interested in taking advantage of the lack of taxation and in doing business without all the restrictions that exist everywhere else in the world,” says Mohamud. “However, many also complain that it’s difficult to do everything without the basic protection governments should provide – like guaranteeing contracts.”

There’s clearly a lot of opportunity for members of the diaspora setting up businesses – but can this serve a social purpose too? Unemployment is high, particularly among those under 30 (around 70 per cent of the population). Mohamed Ali, a Somali-American, established the Iftiin Foundation with his sister in 2012. A social enterprise, the foundation aims to bring together members of the diaspora and locals by teaching leadership skills to young people in Mogadishu and connecting entrepreneurs to funders. “Many of these young people have nothing to do and are at high risk of being engaged by criminal or terrorist organisations,” he says. “They are a vulnerable population. Entrepreneurship is a way to generate employment on a grassroots level, to provide these young people with opportunities and to give them the chance to take control of their lives.”

The young people Iftiin works with are full of ideas; one young man remodelled coffee machines to run off coal, bypassing the problem of prohibitively expensive electricity. “The biggest challenge is not finding people who are entrepreneurial,” says Ali. “But over the last 20 years, a lot of the business activity has been informal. We want to create an environment where international investors would be interested in coming in.”

Of course, there is no clear distinction between the financial interests of the diaspora and locals; the Somali economy has always been propped up by huge remittances from abroad, which some estimates put at around $1 billion (Dh3.67bn) a year. “It’s a hugely important part of the economy and perhaps more importantly, the social safety net of Somalis,” says E J Hogendoorn of the International Crisis Group.

Today, the security situation and the economy remain closely linked. “Particularly outside Mogadishu, the business community can pay a high price,” explains Osman. “If control of an area switches between government and rebels, businesses can be accused of collaborating with the other side.” This can translate into the kind of protection economy seen in Afghanistan and other post-conflict countries.

This ongoing instability is certainly slowing the country’s economic development, but the return of the diaspora and the associated strengthening of the private sector could help to secure peace. “The business community has injected a huge amount of money into politics,” says Osman. But there is a long way to go. “The government must build legitimacy beyond Mogadishu and something must be done about Al Shabab,” says Marchal. “More funds must be available and skills and training improved. There are a lot of basic issues to address. It’s not impossible, but it will take time. Things must be moved politically first, and that doesn’t seem to be happening.”

Some see cause for optimism. “There’s a cycle of poverty, hopelessness and conflict,” says Naima Ali, a Somali woman who recently moved back from the UK to work for an NGO. “If you give people options for their future and opportunities to work, then perhaps we can break that cycle.”

Source: the National

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar