Analysis: Battle between 2 visions of Islam in Somalia could open way for al-Qaida foothold

KATHARINE HOURELD NAIROBI, Kenya (AP) — As battles rage between Somalia’s Western-backed government and Islamist insurgents, another conflict is being fought behind the scenes between competing versions of Islam.

KATHARINE HOURELD NAIROBI, Kenya (AP) — As battles rage between Somalia’s Western-backed government and Islamist insurgents, another conflict is being fought behind the scenes between competing versions of Islam.

The winner may determine not only the future of the failed state, but whether al-Qaida establishes permanent bases in the strategically vital Horn of Africa.

Fighting has intensified in the past two weeks as insurgents attempt to push the government from the capital; nearly 200 people have been killed. The bloodshed has been fueled by the arrival of hundreds of radicalized foreign fighters who, experts fear, could use Somalia as a base for terror in the region.

It’s a pattern that has played out in bloody conflicts around the world, including Chechnya, Afghanistan, and Iraq: petrodollars from oil sheikdoms in the Middle East pay for fighters to travel to far-flung wars.

Experts now fear Somalia has become a magnet for such fighters.

“The radical factions need to boost their forces, and that means inviting in more foreign fighters,” Mark Schroeder, an analyst for the international intelligence company Stratfor, told The Associated Press.

Last year, the Islamist insurgency split, and its more moderate wing now forms the government. But analysts say fighters from countries including Pakistan, Yemen and Saudi Arabia are reinforcing the more extreme insurgent factions fighting government forces.

Now two different types of Islam are struggling for dominance, adding sectarian violence to what has mainly been a clan-based conflict.

Arid Somalia’s camel-herding nomads and their descendants traditionally observe Sufi Islam, a relatively moderate form of worship that allows the veneration of respected saints. But in recent years, Somalia’s insurgent militias have also begun to follow austere Wahabi Islam — rooted in Saudi Arabia and practiced by Osama bin Laden and the Taliban.

Wahabism is a component of jihadi Salafism, a doctrine that preaches spreading a strict interpretation of the Quran, the Islamic holy book, through violence.

“The jihadi Salafists try to use pre-existing disputes that are tribal, social or political to spread their religious and political agenda,” said Khalil Al-anani, an expert on political Islam at Egypt’s Alahram Foundation.

Currently, the government and its Sufi allies and the insurgents and their foreign reinforcements appear to be at a stalemate.

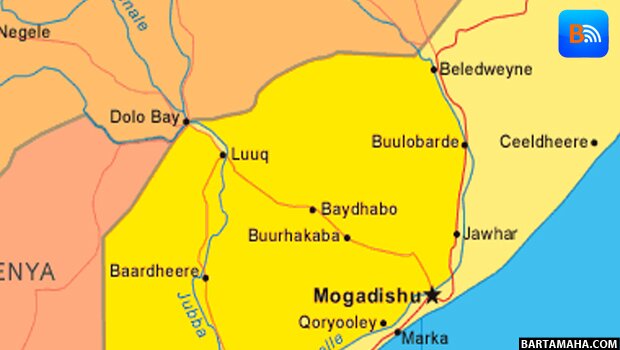

The government cannot break out of the few pockets of the capital controlled by its 3,300 troops. But neither can the insurgents dislodge the government from the airport, presidential palace or other key installations, where the administration is supported by around 4,350 African Union peacekeepers. Government-allied Sufi militias also hold parts of central Somalia. Many analysts say those militias have received weapons and training from neighboring Christian Ethiopia, which is concerned about the Islamists’ links to rebels on Ethiopian soil.

Experts say the foreign fighters are leading to increasingly sophisticated attacks by the insurgency.

The U.N. Special Representative for Somalia, Ahmedou Ould-Abdallah, said this week there are around 300 foreign fighters in Somalia and they “are the best organized, the best disciplined and organized force” behind recent attacks.

On Sunday, Mogadishu’s deputy mayor said the first known suicide bomber of non-Somali origin blew himself up along with six soldiers and a bystander. American officials say just under 20 Somali-Americans are believed to have traveled to Somalia, and linked two of them to suicide bombings in the north of the country.

Osama bin Laden offered his support to the insurgents in a tape called “Fight on, champions of Somalia” last March. The Somali president denounced the tape, as did Sheik Hassan Dahir Aweys, an Islamist insurgent leader who last month returned from two years of exile in the pariah nation of Eritrea. Aweys is listed by the U.N. Security Council as a sponsor of terror and spent a year fighting in Afghanistan, but some analysts say his agenda differs from that of the main insurgent group — al-Shabab — because he puts Somali nationalism first and jihad second.

Other insurgent leaders welcomed Bin Laden’s message, underscoring the tensions within their movement. Sheik Mukhtar Robow, a former Shabab spokesman, described his militia as “students” of al-Qaida who seek a merger with the group.

Although the Islamists have shown themselves willing to fight together to defeat a common enemy, analysts like Schroeder say those alliances would probably come under severe strain if the insurgents managed to seize power.

Al-Shabab’s statements have caused many to fear that the Horn of Africa, which juts into a pirate-infested shipping route just under the oil-rich Arabian peninsula, could become a safe haven for al-Qaida. The United States accuses al-Shabab of harboring al-Qaida-linked terrorists who allegedly blew up U.S. Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998. The United States has attempted to kill suspected al-Qaida members in Somalia several times with airstrikes.

The Wahabis’ strict interpretation of Islam has already alienated parts of the local population. Al-Shabab sparked riots when it tried to ban qat, a popular mildly narcotic leaf chewed by many Somalis. It also smashed the tombs of venerated Sufi saints and imposed harsh punishments — including the stoning death of a 13-year-old girl. Human rights groups say she was the victim of a gang rape.

The destruction of tombs in particular provoked a backlash among local militias. One, Sufi-led Ahlu Sunna Waljama, began referring to al-Shabab as “the Tombraiders.”

Al-Shabab, whose name translates as “the Youth,” is estimated to have around 6,000 fighters. Last year it issued a statement welcoming its designation by the U.S. government as a terrorist group. It is fighting alongside the Islamic Party, an alliance of four smaller Islamist militias whose strength and ideological orientation is unclear. The group formally named Aweys leader Wednesday.

Aweys is also a bitter rival of Somalia’s new president, Sheik Sharif Sheik Ahmed, a former Islamist insurgent who fought alongside Aweys. Ahmed was elected in January after signing a peace deal with the former administration. He has tried to win over the insurgents by offering peace talks and implementing Shariah law.

But he has not yet selected which clerics will review the country’s laws and his own religious beliefs remain unclear.

Rashid Abdi, a Somalia analyst at the think tank International Crisis Group, predicts the “next battle is not going to be military, it is going to be over what kind of Shariah the country should have.”

___

AP Writer Tom Maliti contributed to this report. Houreld has covered East Africa since 2007.

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar