Aid workers under attack in Somalia

Daniel J Gerstle was in Somalia conducting research on child justice for the UN when a gunman opened fire on him and his guards.

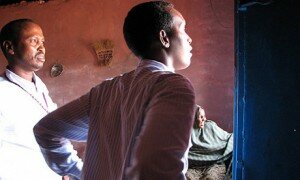

Trapped inside. From left to right: interpreter Mohamed-Omer; government liaison Sak; and Asha, chair of the Horseed women’s group. Photograph: Daniel J Gerstle

My research team and I were near the end of an arduous four-month venture across the north-eastern African nation of Somalia when we came upon an armed man who wanted to kill me. He had wild eyes – bloodshot and rubbed raw – on an otherwise emotionless face. A thick, aggressive Somali man in his forties, he stirred up dust and an entourage as he approached us. He was too husky and commanding to be destitute, too familiar to be a paid assassin. More likely he was fueled by paranoia, high on ‘khat’ narcotic chew, and knew the local authorities could not or would not stop him.

There were 12 in our group that day: Mohamed-Omer, a gentle husband of two, serving as my interpreter; Sak, the fast-talking liaison to the Ministry of Justice and Religious Affairs; four survey enumerators; three drivers; two armed government guards (all Somali); and me, a 33-year-old American consultant to the UN Rule of Law and Security Program. Leaving the divided, central city of Galkayo at dawn that day, our three Land Cruisers had rocketed two hours west across the desert along the southern edge of Somalia’s Puntland State to the remote district of Galdogob.

By late morning it was already scorching, the orange earth between the acacias cracked and dusty. A dozen camels peeked up at us from their troughs in the village centre as we parked. Kids playing in front of the mayor’s office predictably swarmed around us as we climbed out, older passersby swatting at them on our behalf, like they were flies drawn to a mango. Inside, the mayor’s office was a kiln, but we diligently fought the sweat and took down everything he told us about the failure of local rule of law, not knowing that the wild-eyed man and his two cohorts outside were planning an attack.

When I began the UN child justice national survey in January 2007, I had wanted not only to lead my team in confronting legal dilemmas that affected youth. I also wanted to learn more deeply who Somalis were, for what reasons they believed their peace process had failed for 16 years, and why some in the country wished to murder people who came to help.

Being a writer and humanitarian aid consultant from the woodland metropolis of Cincinnati, Ohio, where Americans shop in malls and have never heard of Somalia, much less Puntland, I knew I would both enjoy and suffer for my status as ‘other’. Growing up eager and curious, I had been compelled to make my way to New York, and then to Bosnia, Croatia, Azerbaijan, Chechnya, Afghanistan, and other nations in turmoil; on a quest for truth, purpose, and story.

By the time I arrived in Galdogob, I had already been detained, interrogated, pelted with stones, struck, and threatened in various places around the world – all in the course of participating in and writing about the global humanitarian effort. What came as a surprise to me during this time was that aid workers were not only being targeted for bearing cash, looking different, or allegedly acting as agents for foreign governments. They were also being attacked for not providing aid fast enough.

During our survey, Somalia’s northwest breakaway enclave of Somaliland was in the process of sentencing two men to life sentences for the murders of four foreign aid workers there in 2003-4; the prosecution alleged it was an al-Qaida plot. As my team and I travelled past the very locations of these crimes, I asked Mohamed-Omer to point the scenes out to me. He showed me the very spot in the Boroma tuberculosis centre where the jailed men shot the Nansen Refugee Award-winning nurse, Annalena Tonelli, with whom he had worked. We drove up the desert road outside Hargeisa where they later killed Flora Chepkemoi and her Somali colleague. We even passed the school on the gorgeous Sheikh plateau where the gunmen murdered Richard and Enid Eyeington in their living quarters in 2003.

As if that were not enough foreboding, UN security advisors had warned me against going to certain areas in the north-east just before a Kenyan and Northern Irishman were kidnapped at one site and a separate UN team received a hail of bullets at another. By the end of this macabre review of security incidents, I had come to find out that the common element was not al-Qaida, as western media suggested, but rather the community’s general loss of faith in humanitarian efforts.

Many of the indicted murderers in cases I studied for the survey appeared to have been acting with the consent of their peers, particularly those carrying out “honor” killings or assassination attempts. So what was I, the Cincinnati kid, doing there? The same as most aid workers around the world: trying to do my part, however quixotic, in attempting to reverse the ongoing tragedy.

Over the previous 16 years, Somalia had dissolved into a poorly-governed, disaster-prone country with regional authorities attempting to run mini-states and fighting about where the boundaries lied between them. The north-western enclave of Somaliland, where my survey began, and the north-eastern Somali state of Puntland, where the survey ended, wielded the best hopes for stable government. Yet they were at war with each other.

When the US-backed Ethiopian Army invaded the third part of Somalia this past winter in order to prop up the Transitional Federal Government and destroy an Islamic radical insurgency there, few experts in the region imagined an early resolution to the nation’s troubles.

My team’s survey was meant to address just one of the many aspects of the ongoing national tragedy, but little could be done on any sector without first addressing security. When I finally arrived in Galdogob, I saw exactly why.

“There was a boy who came here with a group of people fleeing Mogadishu,” began Asha, chair of the Horseed women’s group housed next-door to the mayor’s office in Galdogob centre. “A gang of teens argued with him over a mobile phone and they practically killed him—” Asha stopped abruptly, as did Mohamed-Omer who had been interpreting for her.

A cacophony of voices from across the dust flat outside the open steel door erupted and moved closer. I could see a strange woman leading an armed man our way. But since armed men and spontaneous scuffles like that had been so common on our trip, I pressed Asha to continue the story. “The boy was in the hospital,” Asha continued, ears still focused on the scuffle outside, “and then—”

There came a loud metallic clap as the wild-eyed man outside slammed a steel window shutter behind Asha. Our conversation dissolved as our eyes all swivelled toward him at once. He paced back and forth outside the door, looking directly at me. He lifted his Kalashnikov and drew the bolt back to put a bullet in the chamber.

Instantly, our guards Sayid and Ghani, who had been watching the man for a while outside but had not wanted to make aggressive gestures, loaded their own rifles and blocked the doorway, standing between the man and us.

“Mohamed-Omer, what’s going on?” I demanded to know.

“The man outside,” Mohamed-Omer replied. “He said: ‘Bring me the white man so I can kill him.’”

Trapped there in the room with no other way out, we had come eye to eye with Somalia’s every-man-for-himself existential crisis. While the US and Ethiopian-backed TFG forces fought ICU rebels across the southern region, we were left like millions of Somalis in the political void, wishing for a miracle. Despite the guards, the man charged the door at us, firing his rifle.

The loud crack of the rifle shot echoed against the stone walls in the Horseed women’s rights office. For a moment, I looked around at Mohamed-Omer and Sak (who had been closest to the door, and at Asha who had ducked behind the wall at her desk) to see if they had been hit. I imagined Mohamed-Omer falling instead of me and us carrying him into the suburban for a bumpy two-hour drive across the desert to the nearest aid station. But no one had been shot.

From my place behind the wall, I could no longer see what was going on outside without poking my forehead and blue eyes out into the crowd of Somalis. I asked my colleagues to interpret for me, anything, but they could only stare as the mob outside dissolved into the yelps and scuffles of struggle.

Miraculously, Sayid, our baby-faced guard, had launched himself straight at our wild-eyed attacker as he charged. As the assassin pulled his trigger, randomly aiming in our direction, Sayid forced the rifle barrel upward. The bullet had soared through the trees. Immediately, Ghani, the elder guard, joined Sayid in grabbing the man’s rifle while his finger was still on the trigger.

They struggled for what seemed an eternity, the four of us remaining trapped inside the Horseed office. The mob, which had fallen behind the attacker, now came alive, some coming to help the guards subdue the man, others supporting him. Many of the children simply stared at the scuffle without fear. During those moments, I worried that our entire team had put itself at unnecessary risk. Any one of them was as likely to be shot as me. Trapped behind a stone wall like this, I could only imagine what it must have been like for those in troubled areas beyond Somalia, many of whom had not made it out alive.

According to CARE International, at least 83 aid workers were killed in action in 2006, plus 778 wounded and 52 kidnapped. The highest number of aid workers killed in the field came from Afghanistan (26), Sri Lanka (23), and Sudan (15). Somalia was later on the list, despite being called the most dangerous place for aid workers this April by UN Undersecretary General John Holmes.

CARE’s security director, Bob McPherson, believes that the mainstream security strategy built around teaching communities on the benefits of aid and removing barriers between the agency and its local participants (a policy known as “Acceptance”) is failing. With donor governments increasingly sending armed forces and aid to the same places, opposing combatants are treating aid workers as part of the donor government political effort and attacking them as they would diplomats or spies. With U.S. Special Forces actively bombing Islamic militants nearby in Somalia, my work was getting more risky each day.

What makes matters worse for Somalia in the eyes of my colleagues and mine is that such danger on the ground keeps many of the key decision-makers far from the realities of the crisis, leading to peacemakers misdiagnosing the country’s ills and then prescribing the wrong cures.

The greatest example of this, which I discovered in my research, was the decades long peacemaker policy of working actively with many clan and government officials (who the public believed were responsible for mass casualty atrocities), while ignoring the respected moderate Islamic clergy. Eventually, radical Islamists used this point to manipulate the conservative public into supporting their ephemeral and bloody rise to power over the unpopular transitional federal government.

When Mohamed-Omer and Sak completed scouting out the Galdogob mob scene for additional gunmen and were certain the wild-eyed man was fully restrained by our guards, they ushered me past the mob and we jumped into our vehicle to evacuate. Just then, the mayor and his own bodyguard appeared and climbed into our second car. They told us a second gunman had just attacked the mayor’s entourage.

“You see,” Mayor Abdillahi told me when we reached the outskirts of the village. “Our people are furious because we do not have any way to help them. Most of them, like the refugees in the camps here, are good people. They hurt but they simply wait. These men [who attacked us today] believe they are acting for all. But I hope this will not reduce the humanitarian assistance to our people here. Please tell the UN we still need help.”

“The attackers thought you were delivering cash directly to the mayor,” Mohamed-Omer corrected me after we left Abdillahi. “They thought he was embezzling all the aid money since none was reaching the people. I told them the reason the aid does not come is because it’s not safe.” In truth, aid was being delivered there, but it was only a dusting compared to the great need in that area.

When we finally reached our base in Galkayo, Akadir, the team leader in our third car, which had followed from the market 10 minutes behind us, told me that the Galdogob mob had released the wild-eyed man and his partner with their weapons as soon as we escaped. The wild-eyed man had challenged their car as they were leaving.

Having worked there before, Akadir told me he knew this man and that he had killed before, for money. The bankrupt district had nowhere to imprison him, the clan leaders feared a blood feud should they punish him, and the religious leaders, after the Islamic radicals lost the war, feared that acting too strongly would bring suspicion.

Back at the UN compound in Garowe, my colleagues congratulated me on completing the four-month justice survey. Those who knew the details also reassured me that if someone wanted to kill me, I shouldn’t take it too personally. We all sat down to watch the news, aid workers from Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Pakistan, Somalia, and America.

“Rage is by no means an automatic reaction to misery and suffering as such,” Hannah Arendt wrote in her 1970 book, On Violence. “No one reacts with rage to an incurable disease or to an earthquake or, for that matter, to social conditions which seem to be unchangeable. Only where there is reason to suspect that conditions could be changed and are not does rage arise. Only when our sense of justice is offended do we react with rage…”

I had thought of On Violence many times in Somalia, but in Galdogob, without necessarily forgiving the wild-eyed man, I saw the theme in its rightful context. At the scene of the attack, I had felt nothing, really, not even fear. After so many trips to Somalia, Chechnya, Afghanistan, and other nations in turmoil, my tolerance for such tension had grown so high that I hardly experienced adrenaline rushes anymore. But after I returned safely home to Garowe, then New York, and began to think about what would have happened if Mohamed-Omer, Sak, or any of the others had been shot; then the fear, and survivor’s guilt, caught up with me.

The Galdogob gunman and his cohorts wanted to kill me perhaps because I represented the West’s and Somali leadership’s failed promises and contradictory foreign policy. In essence, I was to be killed for not providing aid fast enough.

At last, alive and home, I continue to be confounded by an age-old conundrum, as have many other humanitarian and journalists. The challenges of alleviating suffering for vulnerable families, particularly amid violence and instability, now appeared to me to be more enormous than I had ever imagined. Would I now give up, knowing that my bit of the humanitarian campaign was an even smaller fraction of the required effort than I had believed? Or was I now to have to work harder, exhausted, just to be able to sleep at night? The first thing to do is this: get some sleep and be happy I survived to try another day.

———–

Source:-guardian.co.uk

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar