After Somalia Intervention, Kenya Faces War Within

NAIROBI, Kenya — Widely thought to possess the best military hardware in East Africa but little experience in conventional warfare, the Kenyan military had its moment in the sun after ejecting the al-Shabab terrorist group from neighboring southern Somalia. Now a backlash is in the works, as the region’s biggest economy contemplates a homegrown terrorist threat from sympathizers of the al-Qaida-linked group.

NAIROBI, Kenya — Widely thought to possess the best military hardware in East Africa but little experience in conventional warfare, the Kenyan military had its moment in the sun after ejecting the al-Shabab terrorist group from neighboring southern Somalia. Now a backlash is in the works, as the region’s biggest economy contemplates a homegrown terrorist threat from sympathizers of the al-Qaida-linked group.

After a string of kidnappings along their shared border, Kenyan forces crossed into Somalia in October 2011 as part of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), a military grouping of five African states. By late-September 2012, the joint force had pushed al-Shabab from its stronghold in the port city of Kismayo. In a region wracked by putsches and intra-ethnic violence, the Kenyan armed forces’ successful advance was unexpectedly rapid.

Since then a series of terrorist attacks at home have put Kenyans on edge.

According to the U.S. Embassy, between January 2011 and November 2012, there have been at least 17 attacks involving grenades or explosive devices in Kenya, resulting in the deaths of 48 people, with 200 others injured.

Among the incidents, on Nov. 18, a bomb detonated in a minibus in Nairobi, Kenya’s capital, killing seven people and injuring 30. A month prior, two suspected members of al-Shabab and a policeman were killed in the coastal city of Mombasa during a raid carried out by the local anti-terrorism police. In addition, on Sept. 30, an explosive was hurled into a Sunday school in Nairobi, killing a 9-year-old boy and injuring eight others. And on Oct. 24, a police officer stationed in Nanyuki, a military town 150 miles northeast of Nairobi, was arrested for allegedly collaborating with suspected terrorists.

Key among the terrorists’ grievances are the bilateral military agreements between Kenya and the U.S and U.K. that allow American and British forces access to Kenyan air force and naval facilities in exchange for increased military and economic aid. Nairobi has leveraged training bases for three infantry battalions out of the arrangement, pulling in some $30 million into the local economy each year.

“Al-Shabab views Kenya as the closest ally of the U.S. government within the region,” says Oduor Ong’wen, country director of the Southern and Eastern African Trade, Information and Negotiations Institute. “Their message is not just to Kenyans but to the Western world, of which the U.S. is the face.”

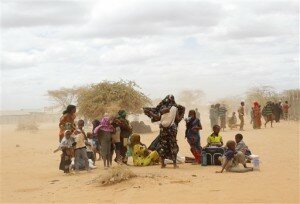

Adding to Nairobi’s anxiety are the approximately 2.4 million ethnic Somalis living in Kenya, who make up 6 percent of the Kenyan population.

Following a civil war in Somalia in 1991 that left the country with no central government, many Somali nationals have sought refuge in Kenya. Now Kenya hosts the largest group of Somali refugees, a phenomenon Ong’wen says “makes it possible for terrorists from Somalia to camouflage [themselves] with the local populace.”

The relationship between the Somali expatriate community and successive Kenyan governments has routinely been strained, stretching back to the eve of Kenya’s independence in 1963, when Kenyan Somalis fought an unsuccessful four-year secessionist conflict — the Shifta War — to create a Greater Somalia.

Ethnic Somalis trace their ancestral roots to Kenya’s Northern Frontier District, a region that shares a porous border with Somalia.

“Concerns have been raised of a potential ‘fifth column’ inside Kenya. Al-Shabab has played on those fears, promising terrorist attacks inside Kenya,” wrote Richard Downie, deputy director of the Africa Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington in a question-and-answer session earlier this year.

Current and former top members of al-Shabab who trace their ancestry through Kenya include Fazul Abdullah Mohammed, mastermind of the 1998 bombings of the U.S Embassies in Kenya and Tanzania; Sheikh Ahmed Iman Ali, who left Kenya for Somalia in 2009 and is the de facto leader of the Kenyan al-Shabab fighters in Somalia; and the late Sheikh Aboud Rogo Mohammed, a self-declared Islamist extremist accused by a U.S. report of arranging funding for al-Shabab and engaging in “acts that directly or indirectly threatened the peace, security or stability of Somalia.” Mohammed was shot dead in August by unnamed assailants in Mombasa.

Also alarming is a phenomenon that has seen typically young Christian converts to Islam, drawn from urban areas of entrenched poverty, joining the ranks of the terrorist group. Reports widely circulated in the local media indicate that a fresh recruit is offered a monthly stipend of at least $2,500 by covert al-Shabab agents using nongovernmental organizations as fronts.

According to Mutuma Rutere, director of the Center for Human Rights and Policy Studies, a regional think tank based in Nairobi, the attacks on the Kenyan homeland are unlikely to cease anytime soon.

“Kenya is on the front line, while the rest of the countries that form AMISOM are to be found on the buffer zone,” he said. “So it’s widely expected that Kenya would and will receive more attention from al-Shabab.”

As a long-term strategy to counter the threat, the Kenyan government has initiated community policing aimed at penetrating enclaves thought to harbor al-Shabab sympathizers, while offering an informal amnesty to local al-Shabab sympathizers who disavow the movement. The government has also sought to mobilize influential Muslim leaders to publicly condemn the group, even as it beefs up its security apparatus with help from the U.S. and Israel.

However, Mutuma said that there seems to be a disconnect between gathering information and acting on it. Other shortcomings hampering the government’s efforts include poor remuneration for security agents and political fissures that stymie the passage of strong anti-terrorism laws.

Clearly Kenya will have to do more to address the problem. On Dec. 6 and 7, Nairobi experienced two more attacks thought to be terrorist-driven.

Charles Wachira is a Kenyan journalist who writes on regional politics in East Africa, business and human rights. He holds a degree in political science and economics from the University of Nairobi.

Source:- World Politics Review

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar