Bombings won’t help stabilise Somalia

The killing of Saleh Ali Nabhan, a leader of al-Shabab, in Somalia yesterday dramatically reduced the list of wanted terrorist individuals in the country. I say dramatically, because the total number of known terrorists in Somalia is no more than half a dozen. This is the paradoxical story of the war on terror in Somalia.

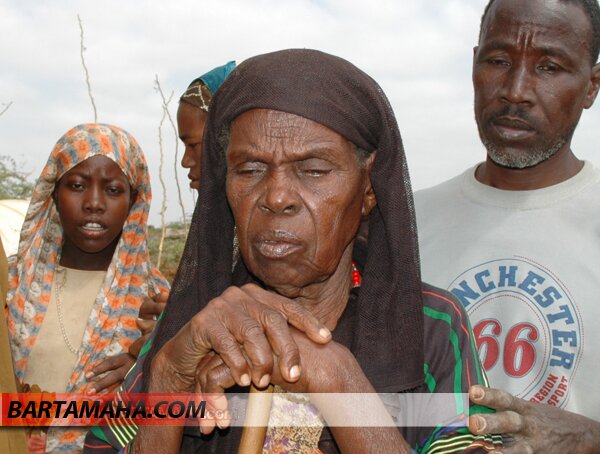

On the one hand, the implication of terrorism, its related activities and global reach, were not significant enough to generate serious international involvement to deal with the country. This is why we continue to see ad hoc military strikes here and there without any coherent strategy to stabilise the country, dissociate thousands of young people from becoming radicalised and, most importantly, provide vital humanitarian assistance to millions of Somalis. On the other hand, the terrorist infrastructure in Somalia is severe enough to deny the country any sense of normality and stability, or for governance to take root.

Immediately after 11 September 2001, the US decided that global terrorist networks were not rooted enough in Somalia to warrant US involvement there – militarily, diplomatically or financially. The policy of containment which was put in place really seemed to mean “we will watch the country instead of help to fix it”. To the frustration of the UN, Somali politicians and neighbouring countries, the US did not play an active part in the Somali peace and reconciliation process. Even more bizarrely, during the peace talks, the US security establishment preferred to work with warlords instead of helping to put together a Somali government. As a consequence, the US undermined the peace process itself.

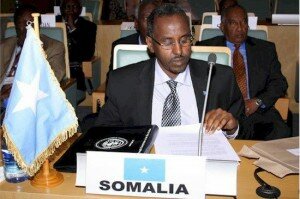

Although I still see US involvement in Somalia as half-hearted, since the arrival of the Islamic courts in southern Somalia in 2006 the US has increased its involvement in peace and reconciliation processes. Today, the US is the Transitional Federal Government’s key partner and is helping it militarily, politically and diplomatically. It is not then a total surprise, or inconvenience, for the TFG to see the country’s sovereignty violated from time to time by countries they consider to be key partners. But is that a reasonable trade off for the risk of losing the support of the Somali people, particularly if civilians are caught in the middle of such operations as happened in the past?

The killing yesterday and the subsequent threat by al-Shabab to retaliate will not, in my view, have significant global consequences. If anything, the operation has scarred the group’s leadership in Somalia. But al-Shabab has a soft target, in the form of the TFG, that is close to home in Somalia’s capital Mogadishu and that they might retaliate against. The government is not strong enough to deal with insurgents and neither is it resourceful enough to deal with the political fallout of events like yesterday’s security operation. That makes the TFG look simultaneously gutless and feeble.

Eventually, a Somali government has to take full responsibly for what goes on in the country and deal with it. For that, the government will need serious help and serious engagement. Unfortunately, I don’t see that forthcoming in real terms. The operation yesterday in Barave, Somalia, merely allows security personnel to check off another box on their “most wanted” list.

_______

Nuradin Dirie is an independent analyst specialising in the Horn of Africa with particular interest in Somalia. He was former presidential candidate in Somalia in 2009 Puntland Elections and also served as senior special advisor to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)

Source: The Guardian

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar