Black Hawk’s Shadow

Why we don’t care about Somalia anymore. By Jason McLure | Newsweek

Why we don’t care about Somalia anymore. By Jason McLure | Newsweek

Picture Mogadishu in 1992. Marauding militias loyal only to Somali clan leaders stalk the city, looting aid shipments bound for the 1.8 million Somalis facing starvation. Then, from the green-blue Indian Ocean waters, there materializes a flotilla of U.S. transports bearing aid and armed men to deliver it. In the skies overhead, U.S. attack helicopters appear, providing cover for food shipments, while an American spy plane circles the city night and day gathering intelligence on militias trying to disrupt the rescue effort.

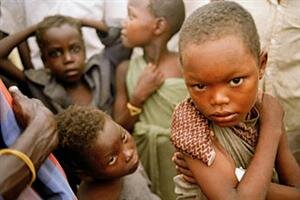

Flash forward 17 years to the same city, still surrounded by squalid refugee camps. More than twice as many Somalis are now teetering on the brink of starvation in what many view as the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. Militias of heavily armed young men still stalk the city hijacking aid shipments. This time, though, no one’s coming to the rescue.

Somalia is in dire straits—maybe worse than ever. An estimated 3.8 million need humanitarian aid (fully half the population), according to the U.N.’s Food Security and Nutrition Analysis Unit for Somalia, which calls the crisis the worst since 1991–92. In the past six months alone, the number of people forced from their homes by fighting—between the country’s barely functional transitional government and Islamist insurgents—has grown by 40 percent, to 1.4 million. Most live in squalid camps that a new report from Oxfam calls “barely fit for humans.”

So why don’t we care anymore? The answer lies not only in how the giant U.S.-U.N. mission to Somalia came undone—in the ashes of the Black Hawk Down firefight in October 1993—but in a legacy of failures by both Somali and Western leaders to cure the country’s ills.

Some things, of course, have changed in the last 17 years. The collapse of the dictator Mohamed Siad Barre’s regime in the early 1990s caused a civil war between the country’s byzantine network of clans, leading to a famine that killed an estimated 300,000 people. Spurred by television images of mass starvation, President George H.W. Bush, just weeks after losing the 1992 election but before his successor’s inauguration, assembled a 33,000-strong U.S.-U.N. mission, known as UNITAF, to stop the famine.

The operation, which included 28,000 U.S. troops, represented Bush’s vision of a new world order in which the world’s lone remaining superpower would work together with the U.N. to douse the world’s geopolitical brushfires. Ukrainian helicopter pilots who only two years earlier had trained for war with America now passed vodka bottles to U.S. soldiers as they choppered them in to save dying Africans.

What few recall today is that in the early months of 1993, the mission effectively halted the famine. But the new Clinton administration made a bold and fateful error in choosing to take sides in Somalia’s civil war. On a mission to capture two deputies of Mogadishu’s most troublesome warlord, Mohammed Farah Aidid, two U.S. Black Hawk helicopters were shot down, spurring an epic firefight between U.S. commandos trying to rescue the trapped pilots and Aidid’s militia. Eighteen U.S. soldiers were killed and 73 injured. America’s experiment in peacemaking there ended almost as soon as the horrifying images of the bodies of U.S. servicemen being dragged through the streets appeared on CNN.

Snakebitten, America tuned Somalia out, but the country’s civil war raged on and on—fueled by clan militias and the private armies of businessmen trading in stolen food aid, looted scrap metal, and arms. Wahhabi preachers from Saudi Arabia poured in, finding converts from Somalia’s moderate Islamic population who sought some semblance of order in a world gone mad. A litany of U.N. efforts to establish a government failed.

After a Somali-based cell of Al Qaeda blew up U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998 and again after the September 11 attacks, U.S. intelligence and defense agencies began paying attention, but the West had no heart for nation building in a country as broken as Somalia. Given that it had no oil and only B-list Qaeda suspects, Western policy became more about containing than halting Somalia’s chaos.

After 2004, radical Islamists emerged as a force in the civil war, making aid workers and journalists frequent targets. CIA efforts to counter the Islamists in 2005 by arming a group of mainly secular—but heavily criminal—warlords flopped. In reaction, the population threw its support behind a Union of Islamic Courts government that brought stability but frightened neighboring Ethiopia’s Christian-dominated government, provoking a U.S.-backed Ethiopian invasion of Somalia to overthrow the Islamists, followed by a two-year occupation that ended this January after the rise of an even more radical Islamist militia, Al-Shabab.

Today Al-Shabab, backed by Ethiopia’s rival Eritrea and financed by hardline Islamists from the Middle East, controls most of southern Somalia. The current transitional federal government, known as the TFG, is the 14th attempt by the U.N. to craft a state in the last 18 years. But it holds only a few neighborhoods in Mogadishu and remains largely dependent on about 5,000 African Union peacekeepers and Ethiopian military support for its survival.

The TFG’s annual budget for the nation, about $42 million, is less than that for the city of Concord, N.H. As foreigners have increasingly been targeted, foreign journalists, with the exception of The New York Times’s Jeffrey Gettleman and a handful of others, have stopped coming, meaning Somalia’s plight—beyond the occasional spectacular tale of piracy—has largely disappeared from the world’s newspapers and television screens.

Yet even if Somalia were on the nightly news, it’s doubtful anyone would be watching. After 17 years, the story of internal warfare and fleeing refugees is sickeningly familiar. The crisis, with its chaotic and opaque internal politics, lacks even a proper bogeyman like Sudan’s President Omar al-Bashir. Perhaps worse, Western policymakers, confronted with their own litany of failure, are deeply adrift about what to do.

“There’s fatigue, but there’s also a complete absence of any ideas about how to resolve this,” says Kenneth Menkhaus, a U.N. official in Somalia in the 1990s who is now a professor at Davidson College. “Today you can’t find someone with an answer to Somalia.”

The current TFG seems like the right team to cheer for. When its president, Sheik Sharif Sheik Ahmed, was selected in January, analysts thought his clan affiliation and moderate Islamist background would help him tame Mogadishu. But Al-Shabab launched a massive assault on the capital in May, forcing 200,000 from their homes and nearly toppling the new administration. Ahmed’s chief of staff, Abdulkareem Jama, now estimates that the fledgling government would need $300 million in foreign aid per year and 50,000 more trained troops to turn the tide against the groups now fighting it. Given the fatal ineptitude and corruption of Ahmed’s predecessors (the previous president, Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed, kept a money printing press in the presidential palace, according to the U.N.), that sort of aid has hardly been forthcoming.

As a result, today’s Somali crisis is spurring calls not for a massive intervention to prevent a famine, like the situation of 17 years ago, but instead talk of resignation and disengagement.

“I think that the main thing is recognizing how little capacity we have to solve the problem in Somalia,” saysBronwyn Bruton, an analyst at the Council on Foreign Relations. “To solve the problem would require a nation-building effort, and there’s no reason to believe it would be more successful in Somalia than it has been in Afghanistan. I think the question is: what can the international community do to get out of the way?”

As long as there’s a threat that Al Qaeda might establish a real beachhead in Somalia, full disengagement doesn’t seem likely. But given that there are no resources or political will to empower the TFG and no other good options, Somalia’s deadly stalemate will probably go on indefinitely. If it was American optimism about what it could accomplish that delivered Somalia into disaster 17 years ago, today it’s our pessimism that ensures it stays there.

____

Source: Newsweek

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar