Young men: ‘Searching for something better’

A fighter from Minneapolis was buried in Somalia, and next to him was another man, apparently a Twin Cities convert to Islam.

The call from Somalia carried devastating news, and a twist.

Friends of Mohamoud Hassan got the call nine days ago that he had become the latest Somali-American from Minneapolis to die in his homeland. Buried the same day, they were told, was a companion who went by the Muslim nickname “Abdirahman.”

But “Abdirahman” was not a Somali-American.

The caller from Somalia described him instead as a “Caucasian American” who had fought alongside the Somali men who had come from the Twin Cities.

Abdirahman may have been Troy Kastigar, a 28-year-old from Minneapolis who converted to Islam several years ago, went by that nickname and when last heard from told his mother he was in Kenya.

FBI spokesman E.K. Wilson said he could not confirm reports of Kastigar’s death. His involvement in the Somali conflict would make him one of just a few Americans to become sufficiently radicalized to take up arms overseas on behalf of Muslim fundamentalists.

Kastigar was known within the Minneapolis Somali community as Abdirahman, according to several sources.

Kastigar’s mother, Julie, said last week that she’d heard the rumors that her son may have been killed. But, she added softly, “I don’t know anything.”

Her son left the United States in November to study the Qur’an. She said that he later told her that he was in Kenya, had married and was happy. She wouldn’t say how recently they talked.

“He’s a very big-hearted, loving person who was always very interested in the spiritual,” she said.

It’s not known what prompted his conversion to Islam.

Kastigar, who grew up living with his mother and younger brother, attended Cooper High School in the Robbinsdale School District from 1995 to 1998. He later attended an alternative school, but records show he did not graduate, said Jeff Dehler, a district spokesman.

Records show he has a handful of arrests and convictions for mostly minor offenses ranging from speeding and driving under the influence to lying to police.

In recent years, he had made friends with young Somalis with whom he frequently played basketball, often at the Brian Coyle Community Center in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood of Minneapolis.

One friend who knew him through Mohamoud Hassan said Kastigar was a “skinny kid” who was fond of tattoos and who was turned on to Islam by a brother.

“He was searching for something better, a better life,” said a man who lives at Kastigar’s mother’s house and said he had several long discussions with Kastigar about religion in recent years.

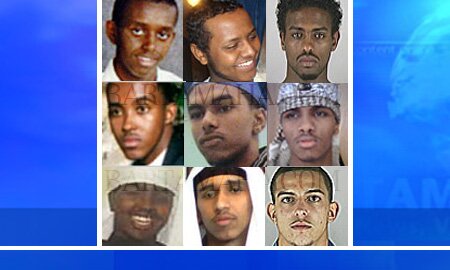

Five Somali men from the Twin Cities have been killed in Somalia over the past 11 months — four since June.

The FBI has confirmed only the death of Shirwa Ahmed, a 26-year-old former college student, the first of the Minneapolis men to die. Ahmed was killed in October 2008 in a coordinated series of suicide bombings in northern Somalia that killed more than two dozen people. He is believed to be the first American citizen to die as a suicide bomber.

Since June, the deaths of four other men — Burhan Hassan, 18; Jamal Bana, 20; Zakaria Maruf, 30, and Mohamoud Hassan, 23 — have been confirmed by their families. In each case, the circumstances of their deaths are unclear. None of the bodies has been returned to Minnesota.

Growing dread

The death last week of Hassan, also known as “Snake,” and the possible death of Kastigar, who some friends knew simply as “Chris,” has convinced many in the Somali community that the others still alive in Somalia may meet a similar fate.

That sense of dread comes as fighting in Somalia, particularly in the capital, Mogadishu, has intensified this summer.

Al-Shabaab, identified by the U.S. government as a terrorist organization with links to Al-Qaida, is one of the groups fighting to establish an Islamic state in a country that has been without a working government since 1991.

Many of the Minnesota men, particularly those who left in the past year, are believed to have been grouped together in the capital, according to Abdirizak Bihi, a spokesman for some of the families of the missing men and the uncle of Burhan Hassan.

“The fighting has gotten worse,” Bihi said. “It has gotten worse in the short time while they were there. … I think the timing is very important, because as soon as they got there the war escalated … and now it’s different. Now it’s Somalis fighting each other that used to fight on the same side. It’s more deadly now.”

Bihi added that the community is “not very optimistic” that the men will return home safely.

Said the father of one of the men, “We are preparing for the worst.”

For months, the father, who did not want to be identified to protect his son, has waited by the phone. Always, he said, he clung to the slim hope that he would someday see his son again.

Now, after the recent deaths, that hope has left him.

“For me,” the father said, “he’s already gone.”

The men who have returned from Somalia face other consequences as part of a sweeping counterterrorism investigation — the biggest since Sept. 11 — into who recruited, financed and trained them.

So far, three men — two from the Twin Cities and one from Seattle — have pleaded guilty to terrorism-related charges and await sentencing. They are cooperating with investigators.

Hussein Samatar, director of the African Development Center in Minneapolis whose nephew is one of the dead, said the message to young Somali men is clear: They are either going to be killed in the fighting or jailed for going to fight.

“I really feel a sense of loss and a sense of sadness [for] all the people,” he said. “To go back and be killed just like that, kills me every day.

“They were caught in the middle.”

Writing on the wall

Saeed Fahia, executive director of the Confederation of Somali Communities of Minnesota, said last month that he thought the radicalization of local Somali youth has ended. The combination of the FBI’s investigation, media attention and the deaths of the local men has discouraged other young men from going to Somalia to fight, he said.

Samatar agrees.

“Because of what has happened to them now, how they died, if anybody thought they could do this now, young folks clearly can see the consequences of their actions,” he said.

Samatar said the young Somali men growing up in the United States “are as smart as they come. They read, they are educated. Really, if you look at them, they are savvy. They use technology. They go to school. I really believe the writing is on the wall for anybody who would help Somalia with violence.

“Want to help Somalis? Be somebody who can help in the United States. Not a 20- or 23-year-old shot to death.”

_____

Source: Star Tribune – RICHARD MERYHEW and J AMES WALSH, Star Tribune staff writers

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar