Arts & Culture

Somali Filmmaker Shows Real Lives of Africans in China

Published

2 months agoon

![]() ZHEJIANG, East China — Hodan Osman Abdi swiftly strings together a few phrases to describe herself: a woman, a black woman, a black African woman. She pauses for a second before completing the sentence: “I’m a black, African, Muslim woman who wears a hijab and teaches at one of the leading Chinese universities.”

ZHEJIANG, East China — Hodan Osman Abdi swiftly strings together a few phrases to describe herself: a woman, a black woman, a black African woman. She pauses for a second before completing the sentence: “I’m a black, African, Muslim woman who wears a hijab and teaches at one of the leading Chinese universities.”

“You don’t find that every day,” says Abdi with a smile. The Somali native is currently a researcher and lecturer on African film and TV at the Institute of African Studies of Zhejiang Normal University (ZNU) in the city of Jinhua. “A person like me breaks so many stereotypes, not just in China but across the world,” she says. “But in China, I’m breaking even more stereotypes.”

The Chinese media often links Africa and its people to war, famine, and poverty, she says, while positive stories are usually left untold. A new documentary titled “Africans in Yiwu” aims to change that. Abdi co-directed the film with her colleague, filmmaker Zhang Yong, and also features in the film alongside 18 others, who share their experiences in China — from facing discrimination to finding love.

Yiwu, a manufacturing city about two hours from Shanghai by train, is popular among migrants due to its business prospects — it boasts the world’s largest small commodities market — and its multiculturalism. In recent years, people from various African countries have settled in the city for business or education. At a Mauritanian restaurant popular with ZNU’s African students, Abdi dishes out details of her China story over beef kofta: It all started in Yiwu 12 years ago when her uncle, who has lived in the country since the 1980s, persuaded her to study there while her cousins traveled in the West. Since then, Abdi has mastered the Chinese language; received undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral degrees; and witnessed the nation’s sweeping changes, which she describes in the documentary.

Hodan Osman Abdi records her voice in the studio, Zhejiang province, May 7, 2017. Courtesy of Hodan Osman Abdi

“Since I came, one thing that hasn’t changed — with regard to being African or foreign — is curiosity,” she says. “People are curious about your identity, who you are, and where you come from.”

With their new film, Abdi and her co-director aim to counter stereotypes and bring African voices to the forefront. The filmmakers describe the documentary as an effort to shine a spotlight on African communities in China other than those in the southern port city of Guangzhou, home to 16,000 people from across Africa, according to official estimates.

“Africans in Yiwu” has been shown at cultural and film festivals in London, Zambia, and Tanzania, and will debut on state-run China Central Television in January.

Sixth Tone sat down with Abdi in her office at ZNU’s African Film and TV Research Center, where she spoke about the documentary, being black in China, and the role media can play in breaking out of conventional narratives. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Sixth Tone: How is “Africans in Yiwu” taking a different approach to typical depictions of Africa and Africans?

Hodan Osman Abdi: One of the core concepts of our film is getting African stories out in African voices. It’s allowing people to tell their own stories from their point of view. They are speaking to the Chinese audience and telling them who they are, what their culture is, how they assimilate, and what are the difficulties they face.

At the same time, they are telling people in their own countries in Africa and the rest of the world what kind of lives they are living in China — it’s a balanced [depiction]. This is the message we wanted [to send], and we didn’t want to tarnish it with our opinions and voices.

Sixth Tone: All the characters in the film speak fluent Chinese. Did you choose them to better reach Chinese audiences?

Hodan Osman Abdi: Most of our characters do speak Chinese, and as film directors, we have to think about our audience. Our [target] audience is the Chinese people, and we want our characters to be able to connect with them. So it was intentional to try to find characters who spoke fluent Chinese. But at the same time, we also wanted to find people who had lived in China for different [lengths of time]. Through their eyes, we can see changing patterns in behavior, treatment, and communication.

Sixth Tone: As one of the characters in the film, what’s the most important message you wanted to convey?

Hodan Osman Abdi: I wanted to address the racial stereotypes we face as African women [in China]. I wanted to tell other African women that their identities do not restrict them; it’s only their minds that restrict them. So if they set their minds to achieving something, their hijabs will not stop them, their religion will not stop them, and their skin color will not stop them. As long as they have the knowledge and the ability, they can walk into any space and demand respect.

I am very bubbly and open to conversation. I portray myself as a fun character in the film who is giving out [relevant] information in a way that would allow people to watch, enjoy, and — in the end — get [to know more about Africa and Africans].

Sixth Tone: Both you and your co-director are academics who work in and research media. How did your background in these fields affect your decision to make the film?

Hodan Osman Abdi: As scholars, our mission is to deliver our message to the widest range of audiences. [Presenting it visually] gives it access to a lot of people. You can spend two years writing a report, and you wouldn’t get 10 people to read it. But if you spend a month making a short video, that message could be viewed by billions of people.

Sixth Tone: Do you think Chinese people’s perception of Africans has changed since you first arrived in China?

Hodan Osman Abdi: Within the last 12 years, China has been on a very fast track of [development] and change, but there is still widespread ignorance within society. They don’t know much about Africa and what it’s like other than what they see in media, which isn’t produced by Africans. So there are misconceptions that are still there. And through this film, we are trying to address these misconceptions and bring out our human side and our efforts to change those ideas.

Sixth Tone: Why do you think Chinese media depictions of Africans are often inaccurate? How does this reflect the general perception of black people in China?

Hodan Osman Abdi: The media do reaffirm the stereotypes but can also dispel the stereotypes and change the conversation — this is what our documentary is trying to do. We are trying to show the African community in China as human beings who suffer loss; who feel happy; who want to get married, fall in love, and obtain Ph.D.s. These are common things that people from all around the world share. We are presenting them as human beings, not as sensationalized or exoticized images.

The issue with media is that they have sensationalized or exoticized the African image, and it’s because of a simple reason: Though China has different ethnic minorities, it’s still a monolithic society. Diversity does not exist.

Awareness of these issues within the Chinese community has not been raised to the extent that it should. If there were more conversations about these issues, I’m sure a lot of people would reach a consensus on what is appropriate and what’s not politically correct.

Sixth Tone: Why is this awareness still low, and how long will it take to change inaccurate perceptions of Africans in China?

Hodan Osman Abdi: It’s a subject so far and remote from [Chinese people’s] lives, and people don’t tend to be curious about or research issues that are removed from their everyday lives.

Right now, as China is becoming one of the biggest powers in the world, we see a huge influx of people from all around the world. So there is change, and it’s a lot better than 12 years ago. As China engages more with Africa and the rest of the world, people are opening to a lot of opportunities [in education and business]. Now, some Chinese people know more about my country than I do. There is that interest right now as China opens up. We can’t expect [the changes] to happen within a day. It will take time, and I do see signs of change.

You may like

-

MINNESOTA: Gustavus professor, student to show documentary on Somali-Americans

-

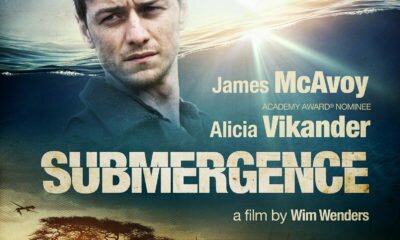

First Look: Submergence is a Love Story with Jihadist Fighters in Somalia Directed by Wim Wenders

-

Kenyan short film on Mandera bus attack nominated for an Oscar

-

Living With the Pirates of Somalia

-

Bollywood film on pirate attack of Somalia underway

-

Aamir Khan: The snake charmer – Witness

Africa

Warlord’s fighters become movie stars as Ugandan cinema booms

Published

4 days agoon

Feb 21, 2018

BLOOMBERG — Opio was 16 when he was abducted by a Bible-quoting warlord and forced into a militia notorious for massacres and sexual slavery. Two decades on, he again took up a rifle — this time playing one of his former comrades in an award-winning Ugandan movie.

As the cameras rolled, he and other actors stormed a village set, shot at civilians and were ambushed at a river crossing. It was all for ‘The Devil’s Chest,’ one of two feature films about Joseph Kony and his rebel Lord’s Resistance Army that was made on location in northern Uganda last year and stirred some painful memories.

“I felt it all coming back, the frustrations, the helplessness and how sometimes I would feel that I just wanted to die,” said Opio, who’s now 38 and spent seven years in the LRA before fleeing and accepting a state-sponsored amnesty. “But at the end of it all, I knew it was just a movie — I had already left that real life in the past.”

Uganda, too, has moved on from the chaos sown by Kony’s militia, which may have been responsible for 100,000 deaths in central and eastern Africa in the past three decades. There’s been an investment in oil exploration and infrastructure in the north, which the LRA terrorized until 2005, while the capital, Kampala, is touted as a hot new nightlife spot. Now at peace — and still under the iron rule of President Yoweri Museveni — U.S. ally Uganda is a regional heavyweight, sending troops to Somalia and South Sudan.

The country isn’t a complete stranger to Hollywood: ‘The Last King of Scotland’ recreated the despotic 1970s rule of President Idi Amin, while Lupita Nyong’o played the mother of a chess prodigy in Disney’s ‘Queen of Katwe,’ which takes its title from a Kampala neighbourhood. Recent years, though, have brought a surge in locally funded films. Museveni’s drive to remain in office may have curbed political expression, but it hasn’t dampened creativity in an economy that’s almost quadrupled in size since he took power in 1986.

At least 700 Ugandan features and short films have played at festivals in the past five years, according to Ruth Kibuuka, content development manager at the Uganda Communications Commission, the industry regulator. While quality was initially “wanting,” it has “greatly improved,” partly due to technical training, she said.

There’s still a long way before Uganda challenges Nollywood, Nigeria’s film industry that produces movies at a rate second only to India’s. That’s despite the efforts of Nabwana Isaac Godfrey. The founder of Wakaliwood, a studio that turns out scrappy, fast-paced action movies from a Kampala slum, he says he’s directed about 60 since 2005 — at less than $300 each.

Driving Passion

“The industry is growing at a very good speed and it’s passion that is driving it,” said Godfrey. His most famous production,‘Who Killed Captain Alex?,’ showcases the crude computer-generated effects and over-the-top violence that’s won him a cult following outside Uganda.

For director Hassan Mageye, ‘Devil’s Chest’ commemorates the insurgency’s victims while showing that people have moved on. It won best feature at Uganda’s main film festival in September but hasn’t yet been widely released. He estimated about 90 percent of the 400-strong cast were affected by Kony’s rebellion, including some ex-fighters.

Roger Masaba, who portrayed Kony, said he was advised by some of the cast who’d met the real man. The 47-year-old said he was surprised not everyone off the set in the north expressed dislike for the warlord. While he was in costume, some even thought he was Kony.

Kony, who’s been indicted by the International Criminal Court and still on the run, went on to plague South Sudan and the Central African Republic with a much-diminished militia. His former fighters in Uganda were mostly granted amnesty by the government, which has provided counseling and outlawed discrimination against them.

There’s a strong local appetite for stories about Uganda’s past, according to Steve Ayeny, the director of ‘Kony: Order From Above,’ another feature about the rebels and their captives filmed at a northern army base. He said about half his 445 actors and extras were former insurgents.

Reenacting the lynchings and burning of villages “was not easy,” said Ayeny, who had friends killed during the period his film portrays. “Because they were the truth, we just had to deal with it and say, ya, let’s move on.”

Arts & Culture

MINNESOTA: Gustavus professor, student to show documentary on Somali-Americans

Published

4 days agoon

Feb 21, 2018

Southern Minn — The hopes and experiences of several Somali-Americans are shown in “(Mid)west of Somalia,” a documentary by a professor-student team at Gustavus Adolphus College.

The film will be shown in its first local public showing at 7 p.m. March 1 at St. Peter High School Performing Arts Center.

Communications studies professor Martin Lang said it was project he embarked on, knowing there was more to the Somali-American story than the reports about terrorism recruitment or conflicts with new neighbors.

“As I’ve lived here in St. Peter for a dozen years now, I’ve come to know more and more of the population in St. Peter and the Somali population in particular,” he said. “I’ve come to know diverse sides of them. It was such a contrast with what I had learned and had known about Somali immigrants smashed up against the people I was meeting and I knew I can’t be the only one surprised at what is below the surface here.”

He and student Noah O’Ryan did the bulk of filming in the summer of 2016.

They talked with Somali-American community leaders as well as people they knew personally, and those connections helped them network more widely. The documentary subjects are all at least part-time students with at least part-time jobs. They primarily live in Mankato or St. Peter; a few are from Faribault.

Lang said they didn’t set out for the film to focus on people pursuing education. He suspects that is a product of the location and so many young Somali-Americans are seeking to do their best.

“Education is a really high priority for Somali families, especially for the first generation,” he said. “The millennial generation feels a really strong responsibility to do right by the family’s sacrifice.”

Lang said Somali-Americans are like many Minnesotans. They value education, want their hard work and effort respected and intend to be “fully fledged, contributing members of our communities in a variety of ways,” he said.

Hanan Mohamud is a senior at Gustavus Adolphus College from Faribault. She is pursuing a psychology degree and wants to be a physician’s assistant. She’s one of the Somali-Americans profiled in the documentary.

She was approached by Lang about being in the film a few years after she was in his public discourse class. She agreed to be involved because “It was empowering and I had a lot to say.” She also connected him to two others.

Mohamud said she agreed, in part, to combat demeaning stereotypes.

“Most people honestly have no idea,” she said. “They think we’re living off welfare and whatnot. A lot of us go to school and only came to the country to get an education.”

Education is something that can’t be taken away and can help their home country. She said the documentary shows what she and others have experienced in the U.S., along with their aspirations and their priorities.

“It’s a very good film,” Mohamud said. “There’s some humor in it and, obviously, there are serious parts. It looked well put-together and he made sure the voices of people he was filming were well heard.”

Some of the documentary’s subjects will be part of a panel with Lang after the showing. The documentary, which runs about 35 minutes, has been shown a few times to small groups, but this is the first large public viewing.

The showing comes as part of the first Thursday film series by the Nicollet County Historical Society and Community and Family Education. It is also sponsored by the college, city Department of Leisure and Recreation Services and Senior Center.

“I think this is an important film because it tells the story of people who live, work, and attend school in this area,” Community and Family Education Director Tami Skinner said. “I hope that it will generate conversations in the community which will lead people to reach out to their new neighbors.”

Lang said he hopes it spurs understanding and conversation.

“The bigger picture for me is communication and dialog and in sort of a difficult political time, dialog is so much harder than it used to be,” he said. “It’s so important for all of us to be able to talk and pay attention to each other at least a little bit. I want to inspire conversation across divides that keep us apart.”

I think this is an important film because it tells the story of people who live, work, and attend school in this area. I hope that it will generate conversations in the community which will lead people to reach out to their new neighbors.

Safy Hallan Farah’s ‘1991’ zine will feature beautiful images and writing culled from the brightest young minds across the Somali diaspora.

Safy Hallan Farah didn’t think there were enough images of Somali people in media, so she took things into her own hands. In the summer of 2017, she conceived of the 1991 zine to “create the images” she wanted to see in the world. Farah, a writer who’s been in published in The New York Times, Vogue, Nylon and Paper, will release the first issue of 1991 later this year. She co-founded 1991 with Mia Nguyen—”even though she’s Vietnamese, she’s really passionate about the project,” Harrah explained—and is working on the zine with former VICE writer Sarah Hagi, model Miski Muse, Hadiya Shirea, and other Somali writers and artists.

Safy Hallan Farah didn’t think there were enough images of Somali people in media, so she took things into her own hands. In the summer of 2017, she conceived of the 1991 zine to “create the images” she wanted to see in the world. Farah, a writer who’s been in published in The New York Times, Vogue, Nylon and Paper, will release the first issue of 1991 later this year. She co-founded 1991 with Mia Nguyen—”even though she’s Vietnamese, she’s really passionate about the project,” Harrah explained—and is working on the zine with former VICE writer Sarah Hagi, model Miski Muse, Hadiya Shirea, and other Somali writers and artists.

“1991 is a Somali culture zine,” Farah told me in an email. “The name comes from how 1991 was the year the civil war broke out in Somalia, ushering a new beginning for Somalis everywhere. My collaborators and I would like to curate and edit work that plays with time and memory. From collage art that explores forgotten vestiges to writing by modern storytellers, 1991 will be at once a time capsule and an exploration of a Somali futurism that reconciles with the tumult of its past all while highlighting the creativity, style, resilience, and tenacity of Somali youth across the diaspora.”

Safy Hallan Farah | Photo by Nancy Musingguzi

VICE caught up with Safy over the phone to talk about her inspirations, growing up Somali-American in Minnesota, and Somali futurism.

Safy Hallan Farah | Photo by Nancy Musingguzi

VICE: Why did you title the zine 1991?

Safy Hallan Farah: I didn’t want people to project onto the name. I also didn’t want to marginalize the project by giving it an obscure Somali word as the name. And I like numerals. When things are in order, they tend to come first. 1991 is a palindrome, so it’s very stylistically interesting to look at. I was keen on not having something look ugly on the magazine because I think some words are ugly, some words won’t look beautiful to the wrong audience, and we want to cultivate a diasporic audience that isn’t necessarily Somali. Having it be called 1991 would be an interesting way to get a message across and have people ask us [about it instead of asking], “What does that word mean?” They’ll ask, “What is the significance of 1991?”

What is the significance of 1991?

We had this dictator named Siad Barre and he was ousted by people who were really mad at him, for good reasons because he sucked a lot. Then a civil war broke out, and that’s why there are so many displaced Somali refugees in countries like the United States, England, Australia, and pretty much everywhere. Somalis are everywhere.

Why is it important for you to have a zine that represents Somali voices?

It’s about [Somali] images. There aren’t images of Somali people that I want out there in the world. A magazine project can help create the images I want to see. Something I’m always thinking is, “Where are the Somali photographers who shoot in the particular styles that I happen to gravitate toward?” Through 1991, I’ve been able to connect with really amazing photographers I didn’t know existed and models. I’m interested in putting more diverse images out there of Somali people, particularly women and youths.

Tell me a little about your personal journey. How did you reach the point where you decided to create 1991 and felt the need to boost the voices of other Somali writers and artists?

I always felt like it was in my best interest to keep my head down and do my work and not create anything of my own, and keep doing what I have been doing, which is publishing articles at different publications, mostly because I felt like I didn’t necessarily know if it was the right time in my life to helm a project like that. I was inspired by my friend Kinsi Abdulleh who runs an organization in London called NUMBI Arts. She started this amazing Somali zine in 2010 called Scarf and she gave me a bunch of issues when I met her in Wales in 2015. Had I not been introduced to her work, I would not be doing this kind of project. It really got me thinking about creating community and creating spaces for Somali people and through just thinking about that over the course of the last three, four years, it’s gotten to the point where I am now, where I can focus on a project like [ 1991].

Image by Ikran Abdille via 1991

Can you tell us about your upbringing as a Somali-American in Minnesota, your relationship with your ethnic identity throughout your life, and how it led you to creating this zine?

Fun fact: I didn’t really speak Somali until I was nine. That’s because I only spoke Somali as a kid and my parents didn’t teach me English, but they taught me how to read [in English] before I was four. When I started kindergarten, I actually realized, “Oh shit, people speak English, I’m a weirdo, I don’t know how to communicate with anyone.” So I learned English really quickly, and I graduated from ESL class after the first couple months of first grade, and then I didn’t speak Somali for years. I completely disassociated from speaking Somali. This is something that happens with a lot of immigrant kids. When I moved to Minneapolis [from San Jose] when I was nine-years-old, I learned Somali because Minneapolis has a huge Somali population. I was going to pretty much all-black, all-Somali schools, and then I learned how to speak and write in Somali. Now I speak pretty fluent Somali. I think my relationship with my culture changed when I started being around more Somali people.

The jilbaab is very gangistar and our mamas and aunties and cousins who choose to wear it are not oppressed. Somali women can dress in any style they want and still be fly and independent. 🇸🇴 🇸🇴🇸🇴🇸🇴

A post shared by 1991 (@1991zine) on

Why did you gravitate toward the medium of collage?

There are going to be a lot of written pieces, but I just like the idea of having that DIY aesthetic that a lot of zines have with collage. But also being design-minded. I really love Apartmento Magazine and The Gentlewoman. I want to strike a balance between good design and DIY.

You’ve mentioned “Somali futurism” in your description of the project. Can you explain what that is?

I remember when I was a senior in high school—most of my friends were Somali and most of my classmates were Somali—and everyone would be like, “Well, I’m gonna study this because then I get to go back to Somalia and do this.” Everyone would say stuff like that. Even though a good chunk of those kids weren’t actually born in Somalia, but everyone was always thinking of Somalia’s future and what’s next for us and what we can do for Somalia. What really interests me is what kind of voices will emerge in the diaspora that will push toward more progressive politics, more interesting sounds and textures and visuals. I’m more interested in the ideas that are going to go back to Somalia, rather than the people and the jobs.

UPDATED: Death toll from Somalia blasts rises to 45: government official

How a High School Soccer Team United a Racially Divided Town

Heartbroken brother paints picture of his sister who was slain by estranged husband

CANADA: Federal court turns down Abdoul Abdi’s bid to pause deportation hearing

London stabbing murders: 18-year-old arrested on suspicion of killing two young men on same night in Camden

Singapore-flagged tanker attacked off Somalia but escapes

BREAKING: 2 blasts, gunfire rock Somalia’s capital

Somalia’s first forensic lab targets rape impunity

Two Somali men stabbed to death in north London as 2018 toll reaches 15

Ismail Mohamed Wants To Be Ohio’s First Somali-American Legislator

BREAKING: 2 blasts, gunfire rock Somalia’s capital

London stabbing murders: 18-year-old arrested on suspicion of killing two young men on same night in Camden

UPDATED: Death toll from Somalia blasts rises to 45: government official

Singapore-flagged tanker attacked off Somalia but escapes

CANADA: Federal court turns down Abdoul Abdi’s bid to pause deportation hearing

How a High School Soccer Team United a Racially Divided Town

Heartbroken brother paints picture of his sister who was slain by estranged husband

INTERVIEW: Somalia gears towards improving its monetary policies

Somalia: Detained Children Face Abuse + INTERVIEW

Families plead for update on Somali deportation case at impromptu town hall

Somalia Tax Argument From Both Sides: Bakara Traders vs The Government

Somalia military court sentences army officer to death

Somali traders boycott business over new government tax

Somali refugees enslaved in Libya return home

Somali Migrants Returning From Libya Tell of Abuse, Horror

Somali government introduces 5% sales tax to boost revenues

LONDON: Crowd pickets Wormwood Scrubs demanding justice following death of inmate

TRENDING

-

Somali News2 days ago

Somali News2 days agoBREAKING: 2 blasts, gunfire rock Somalia’s capital

-

UK23 hours ago

UK23 hours agoLondon stabbing murders: 18-year-old arrested on suspicion of killing two young men on same night in Camden

-

Somali News14 hours ago

Somali News14 hours agoUPDATED: Death toll from Somalia blasts rises to 45: government official

-

Briefing Room1 day ago

Briefing Room1 day agoSingapore-flagged tanker attacked off Somalia but escapes

-

Canada15 hours ago

Canada15 hours agoCANADA: Federal court turns down Abdoul Abdi’s bid to pause deportation hearing

-

Sports14 hours ago

Sports14 hours agoHow a High School Soccer Team United a Racially Divided Town

-

UK15 hours ago

UK15 hours agoHeartbroken brother paints picture of his sister who was slain by estranged husband

You must be logged in to post a comment Login