Minnesota: Panel hears stories from Somalis who call Willmar their home

WILLMAR — The story of Somali refugees settling in Willmar is part of the ongoing story of a city and a nation that has been built on immigration.

WILLMAR — The story of Somali refugees settling in Willmar is part of the ongoing story of a city and a nation that has been built on immigration.

Stories told Thursday highlighted the similarities and differences between new immigrants and those who arrived a century ago.

During two public forums, “Understanding the Somali Culture,” several Willmar residents shared their stories of immigrants’ struggles to fit in.

The panel discussion meetings at the Willmar Education and Arts Center attracted 231 people to a morning session and approximately 420 at an evening session.

According to information presented at the meeting, Willmar has an estimated 1,500 to 2,000 Somali residents. Their major employer is Jennie-O Turkey Store, where 400 to 600 Somali people work.

Downtown Willmar has about 20 Somali-owned businesses, including two restaurants, a coffee shop and shops that sell groceries, clothing or books.

Moderator Greg Hilding spoke about the American story of immigrants.

“In western Minnesota, our community continues to grow and move forward,” he said.

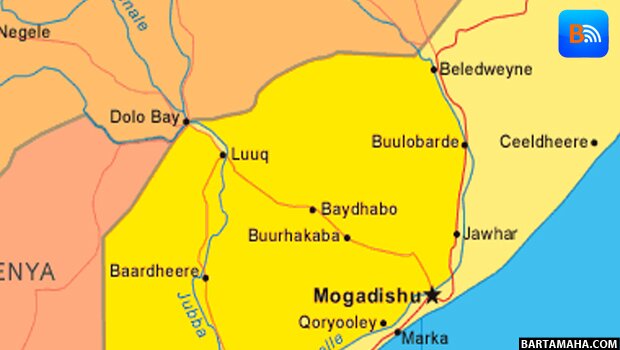

Abdirizak Mahboub, director of the African Development Center in Willmar, gave a short presentation about Somali history and culture. The country has been torn by civil war for the past 20 years.

Most Somalis are Sunni Muslims, Mahboub said, and their religion guides the way they live in many ways. “The mosque is the center for the community.”

Somali women widely adopted the hijab, or head covering, in just the last 25 to 30 years, he said. When civil war broke out, people wanted to make changes, he said, and the hijab became “a preferred article of faith.” When people went to refugee camps after war broke out, “it became protection for the woman to be covered.”

Mahboub listed the five pillars of Islam: proclamation of faith; five daily prayers; giving to the poor; fasting in the month of Ramadan; and pilgrimage to Mecca. Muslims believe Jesus was a prophet.

The Rev. Tim Larson, pastor at Calvary Lutheran Church, talked about his grandfathers, who arrived from Norway when they were 18.

On arrival they asked where people gathered to speak Norwegian and where they worshiped God, Larson said. “They wanted a place to gather comfortably and speak in their native tongue.”

Once people understand new immigrants in that context, he added, “We can learn how to live together and function together.”

Mohamed Sayid, 25, an employee of Kandiyohi County Family Services, helped bring home the context of the refugees’ lives. His memories of his family leaving Somalia are “horrifying.” When their truck broke down, their group had to spend the night by the side of the road. Women and girls slept on top of the truck, but the men and boys were on the ground. One of the members of their group was taken by a lion during the night.

Sayid arrived in Willmar when he was in junior high. He graduated from Willmar and attended Ridgewater College. He participated in the city’s efforts to be named an All-America City when he was in high school.

“Willmar is an All-America City because we are a team,” he said. “Because of my experiences, I am grateful for peace and security, especially coming from a country which doesn’t have that security.”

Sayid said that Willmar is his home. “I’ve tried to move out of here, but I keep coming back,” he joked.

Rachelle Peterson, a community member who recently visited Somalia, shared pictures and stories of her trip to a friend’s wedding. Her photos showed the topography, wildlife and people of northern Somalia.

Her reason in speaking was “to express my appreciation to the Somali community,” she said. “It’s really enriched my life.”

During a question and answer session, Peterson was asked why she was wearing a headscarf in the photos. “I wore that out of respect,” she said. The differences between cultures made her appreciate even more the adjustments Somali people make when they come here, she added.

Sayid provided some comic relief in answering a question about his challenges as a newcomer.

Language and customs both presented some barriers, he said. He told of walking through the school with an armload of books. When a girl waved to him, he couldn’t wave back, so he just lifted a finger. Unfortunately, it was his middle finger — a fine gesture in Somalia, not so great in Willmar. He later apologized and explained to her that it had been a mistake.

Hilding said the cultures aren’t necessarily that different, because Sayid was not the only boy who did something awkward around a girl in junior high.

Two questioners brought up the teaching of Jesus that we are to love our neighbors as ourselves. One man asked whether Muslims are taught something similar.

They are, Sayid said. A problem for Somalis in Willmar is that a language barrier can keep them isolated from their neighbors, he added.

A woman in the audience asked if it was true that a Somali woman who became Americanized was separated from her community.

Mahboub said young men or women who drink or have pre-marital relationships, both forbidden in Islam, can sometimes be disowned by their families. The elders in the community have been discussing how to best deal with such situations.

“This is a big thing for the Somali community — how to adjust to situations that are not part of the traditional culture,” he added.

Source: AP

Comments

comments

Calendar

Calendar