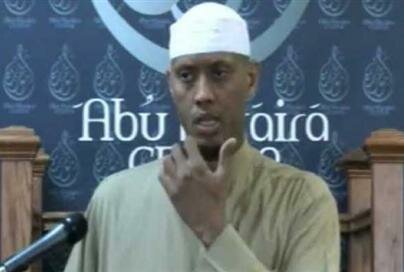

TORONTO — At a mosque in a bleak industrial neighbourhood in north Toronto, Imam Saed Rageah devoted his sermon on Friday to denouncing the suicide bombings plaguing his homeland of Somalia.

TORONTO — At a mosque in a bleak industrial neighbourhood in north Toronto, Imam Saed Rageah devoted his sermon on Friday to denouncing the suicide bombings plaguing his homeland of Somalia.

“This is not in Islam,” he said.

The congregation of the Abu Huraira mosque kneeled and listened, but it was those who weren’t present that made his words resonate: a group of young men who vanished this fall and are feared to have joined a Somali militant group.

Among the missing are Mahad Ali Dhore, a 25-year-old Markham man who fled to Canada from Somalia at age nine and had almost finished his degree at York University when he flew to Kenya and disappeared.

Also missing is Mohamed Elmi Ibrahim, nicknamed “Canlish” after the Scarborough neighbourhood where he grew up. Canadian Security Intelligence Service officers have also been asking members of Toronto’s large Somali community about Khalid Aden Noor, Mustafa Ali, Ahmed Heybe Ahmed, Abdirahman Yusuf and Mohamed Ali Gacal, a Minnesota man who had apparently visited Toronto.

Nobody knows for sure what happened to them, but their families, the imam and counterterrorism investigators are concerned because of a pattern of similar behaviour in the United States, where at least 20 young Somali-Americans have gone missing only to turn up in Somalia with Al-Shabab, an armed Islamist group aligned with al-Qaeda.

The same trend has surfaced to varying degrees in the U.K., Australia and Europe. Last week in Mogadishu, an Al-Shabab suicide bomber killed two dozen people, including three government ministers. He was identified by the speaker of Somalia’s parliament on Friday as a 26-year-old Danish citizen. An earlier suicide bombing was carried out by an American from Minnesota. Five other Americans are believed dead.

“The community is very, very concerned,” said Ahmed Hussen, national president of the Canadian Somali Congress. He emphasized there was no proof the men had joined Al-Shabab but said if they did, the fact they are only five or six out of 150,000 suggests the problem is not widespread.

While families in Toronto worry their sons could meet the same fate, counterterrorism authorities have another concern: what happens if they return to Canada with extremist ideology and terrorist training?

Imam Rageah said he knew some of the men, including Mr. Ibrahim, but described them as occasional congregants who attended prayers only periodically, and said three of them had only recently come to Abu Huraira.

“If anybody would recruit anyone, then these [type] are the perfect target because they’re emotional, they can misinform them easily,” Imam Rageah said in his office this week. (He recorded his interview with the National Post using two video cameras mounted on tripods.)

“They were not people who would sit in the classes and learn and then say, ‘OK, well, let me analyze this, what Islam said.’ But they would just be more emotional, based on their emotions, and people may take advantage of that and just, boom.”

The popular imam never spoke about the missing men in his sermon but he did mention the violence in Somalia. He said he wanted to tackle any misunderstandings that some might have had about suicide bombings, which he said were against the teachings of Islam.

“Before, I don’t see anyone who has that mentality from these young people. We haven’t noticed any extremes in them. But now I don’t know who to trust. I don’t know who has those ideas and ideology, so we need to correct them,” he said.

The imam was at a conference in India when the men vanished. By the time he returned to Toronto, it was already common knowledge in the Somali community and counterterrorism investigators were on the case. CSIS “visited a lot of people,” he said.

He believes the Internet may be to blame.

“The problem is when you have these young people who are sitting in front of the screen, computers and Internet, listening to a talk from YouTube or somewhere, and then they think they know the right knowledge.

“And these guys who are talking to them, they really don’t show all Islam. They just show you what they want to present. So these kids are fed with that information.”

Investigators are trying to determine whether a recruiter was involved. Imam Rageah said the men must have had help but said recruiters do not target mosques because they are so closely watched.

“I mean these kids, they don’t speak the language, they’ve never been back home,” he said. “They don’t know anything about the land. How could they travel from here and go there? There must be some arrangements taking place. That did not happen here, it happened somewhere else so that’s what we should look into, who is doing this?”

The RCMP apparently agrees that mosques are not the problem. A June 2009 report by the National Security Criminal Investigations section says that extremists tend to get weeded out of mosques.

Instead, the report says frustrated and curious youths may go looking for answers outside the mosque, where they become vulnerable to a secret underworld where charismatic extremist ideologues lurk.

“I have six kids and this is my home,” Imam Rageah said. “We left back home because of civil war…. We left there so we can have a better place, better future for our children. If I see a person who is doing such a thing here, in my home, I would not tolerate that.”

Imam Rageah was born in Somalia but, after his parents died, he went to live with his brother in Saudi Arabia. Two of his brothers were killed in the persistent fighting that has engulfed Somalia for the past three decades.

After immigrating to Canada in the 1980s, he studied in the United States and became imam at the Ayah Islamic Centre, a mosque in Laurel, Maryland, that came under FBI scrutiny after Sept. 11, 2001.

During the investigation into the 9/11 attacks, it emerged that two of the hijackers who crashed a plane into the Pentagon, Nawaf al Hazmi and Khalid al Mihdhar, had left their belongings at the mosque two days before the attacks.

The FBI investigated for 18 months and found no link between the mosque and 9/11. But during the investigation, the FBI claimed Imam Rageah had been fundraising for the Global Relief Foundation, a charity that was allegedly tied to Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda. Again no charges resulted and the case was closed.

Imam Rageah returned to Canada in 2003 and after a few years in Calgary, moved to Toronto to work at the Abu Huraira Centre. On his Facebook fan page, which has more than 1,000 members, followers rave about his lectures.

Asked about the FBI investigation, Imam Rageah said the period after 9/11 was “crazy. Sept. 11, whether you are guilty or not, you are guilty … but that’s a different thing. It’s a different ballgame. It’s not what is happening here. My concern right now is, those who went, went. Those who left, they left, for whatever reason, whether it’s testifiable or not. What about the future ones? How can we protect those?”

The Toronto men have been missing for almost two months now and still nobody knows for certain where they are. All that is confirmed is that they left suddenly and without notice, and that at least some of them travelled to East Africa.

Mr. Dhore’s family believes he was recruited in Canada and wants the government to find out who was responsible. He was travelling on a ticket with a Dec. 28 return date. They will be at the airport that day, waiting for him to walk out of the baggage claim.

National Post